Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and other agencies operating programs benefiting veterans and their families fulfill a national promise to veterans. These programs offer important benefits and services, providing health care, disability compensation, education and employment support, pensions, and other benefits to veterans. However, it is also important to consider the fiscal context: because the US national debt has recently reached a record $36.7 billion and government spending exceeded government revenues by $1.9 trillion in Fiscal Year (FY) 2024, this threatens the fiscal foundation that supports veterans’ programs and other vital government services. As a significant component of Federal spending, programs for veterans must be considered as part of a holistic evaluation of the Federal government’s fiscal position to reverse its negative trajectory while fully honoring our national promise to veterans and ensuring they receive the benefits to which they are entitled. Indeed, only through setting the country on a sounder fiscal footing will the US be able to maintain the levels of spending it has promised to veterans and the quality of care they receive.

This Explainer provides a brief history of veterans’ programs; an overview of health care, disability benefits, education and employment programs, pensions, and other benefits for veterans; a description of funding for veterans’ programs; the impact of veterans’ programs; and a discussion of some options prepared by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) for reforms to veterans’ programs that would serve to reduce the national debt.

- The VA is the primary Federal government agency that provides benefits and services to veterans. Veterans may also be eligible to obtain TRICARE and a military pension from the Department of Defense.

- Support for veterans and their survivors has a long tradition, with a variety of health care, housing, disability payment, and pension programs emerging after periods of war. Eventually, these programs were consolidated in 1930 under the Veterans Administration. Legislation in 1988 established the current VA in the Cabinet.

- The Veterans Health Administration provides health care (often directly) to eligible veterans, including preventive care, treatments for injuries and illnesses, functional improvement support, quality-of-life enhancements, and other critical support services.

- The Veterans Benefits Administration offers disability compensation benefits, education and employment programs, pensions, home loan guarantees, life insurance, and family and caregiver benefits.

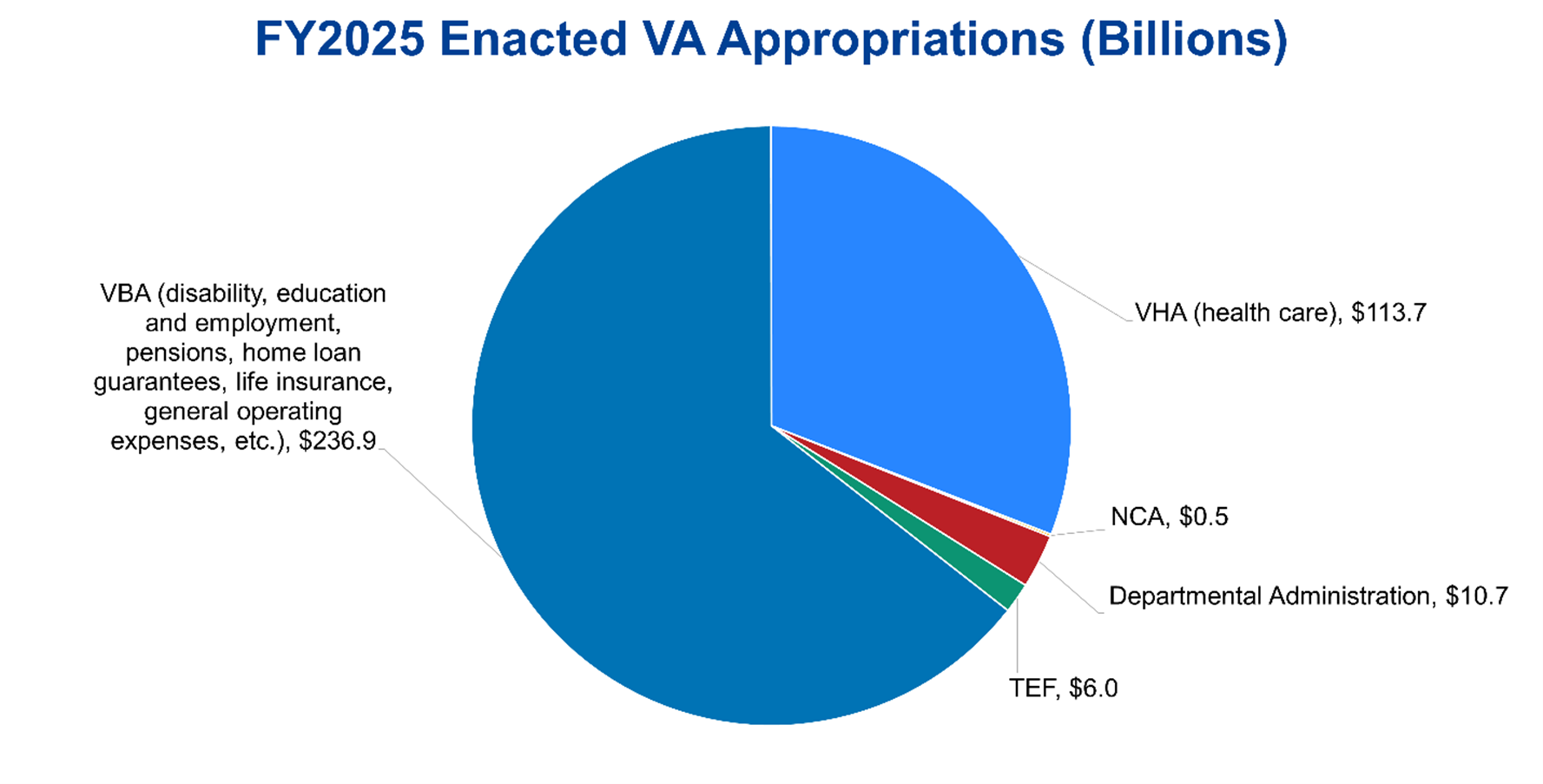

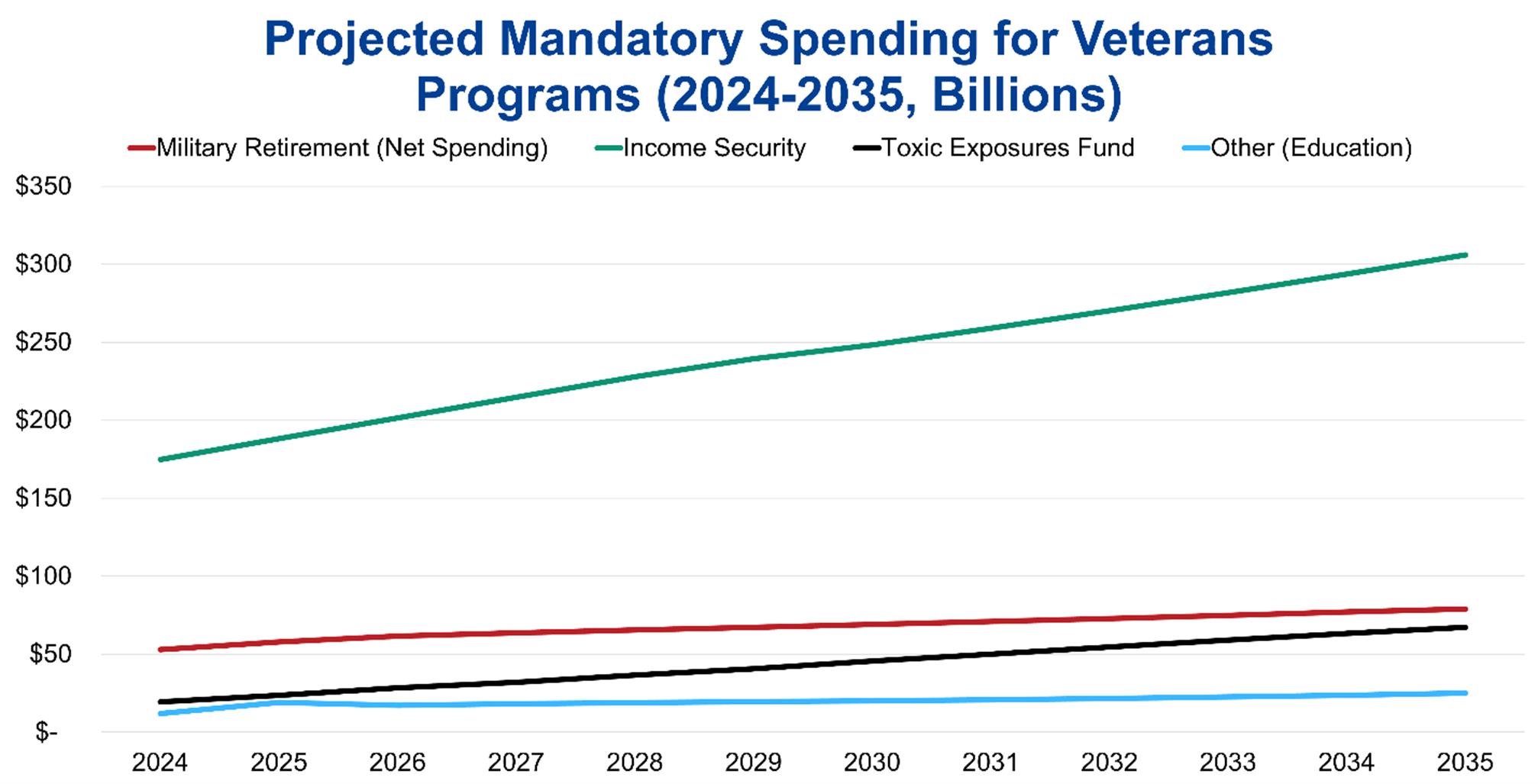

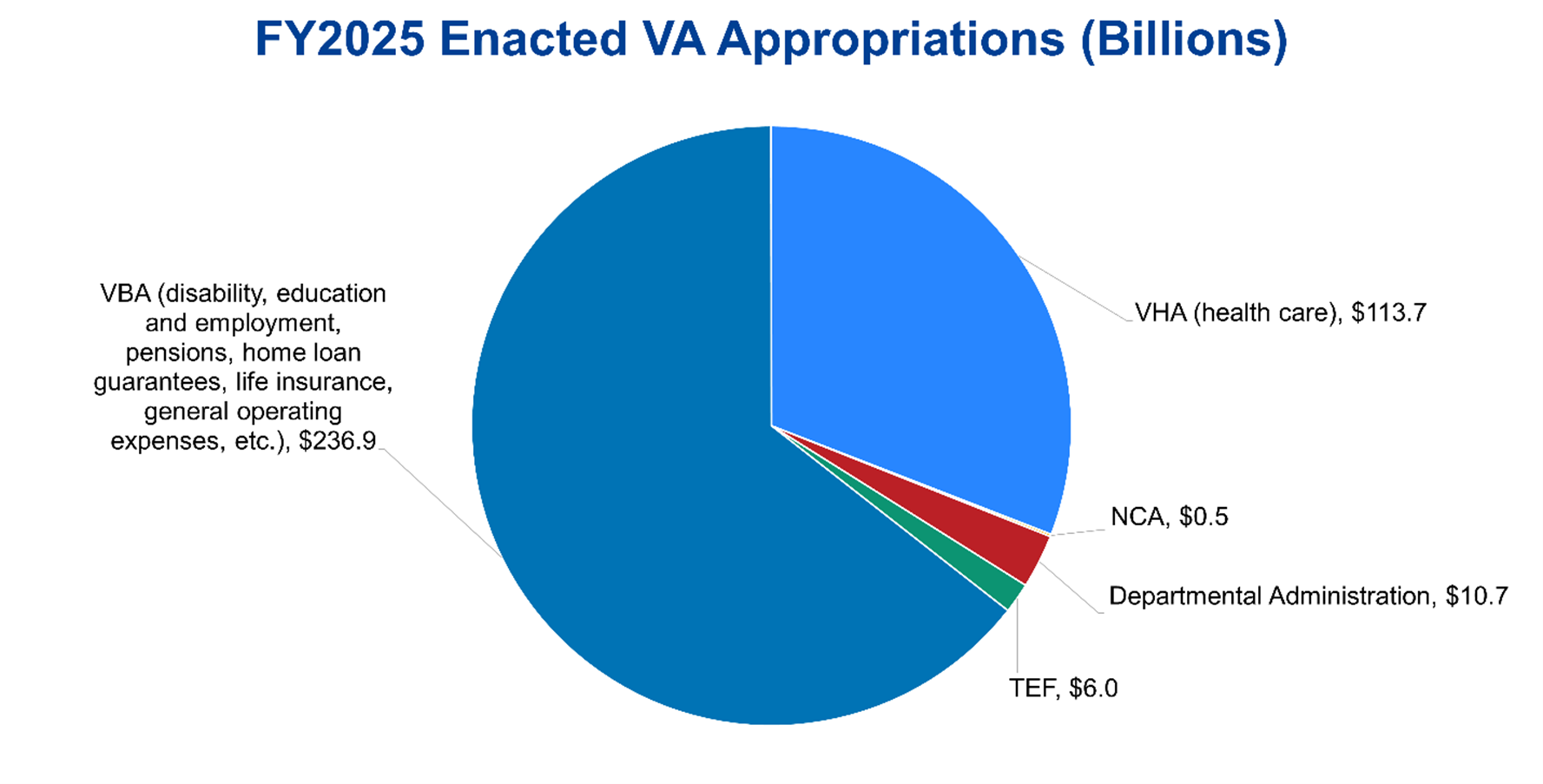

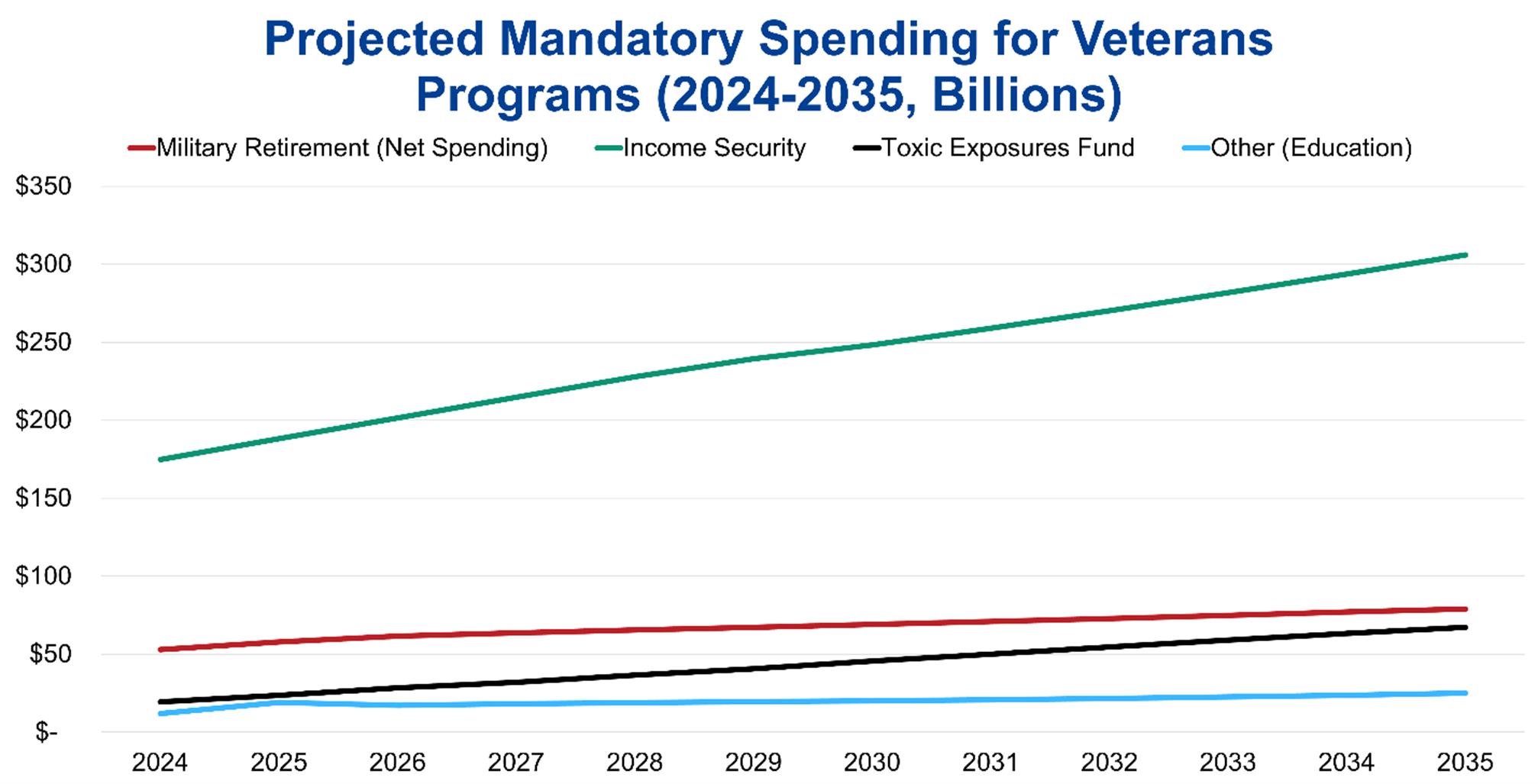

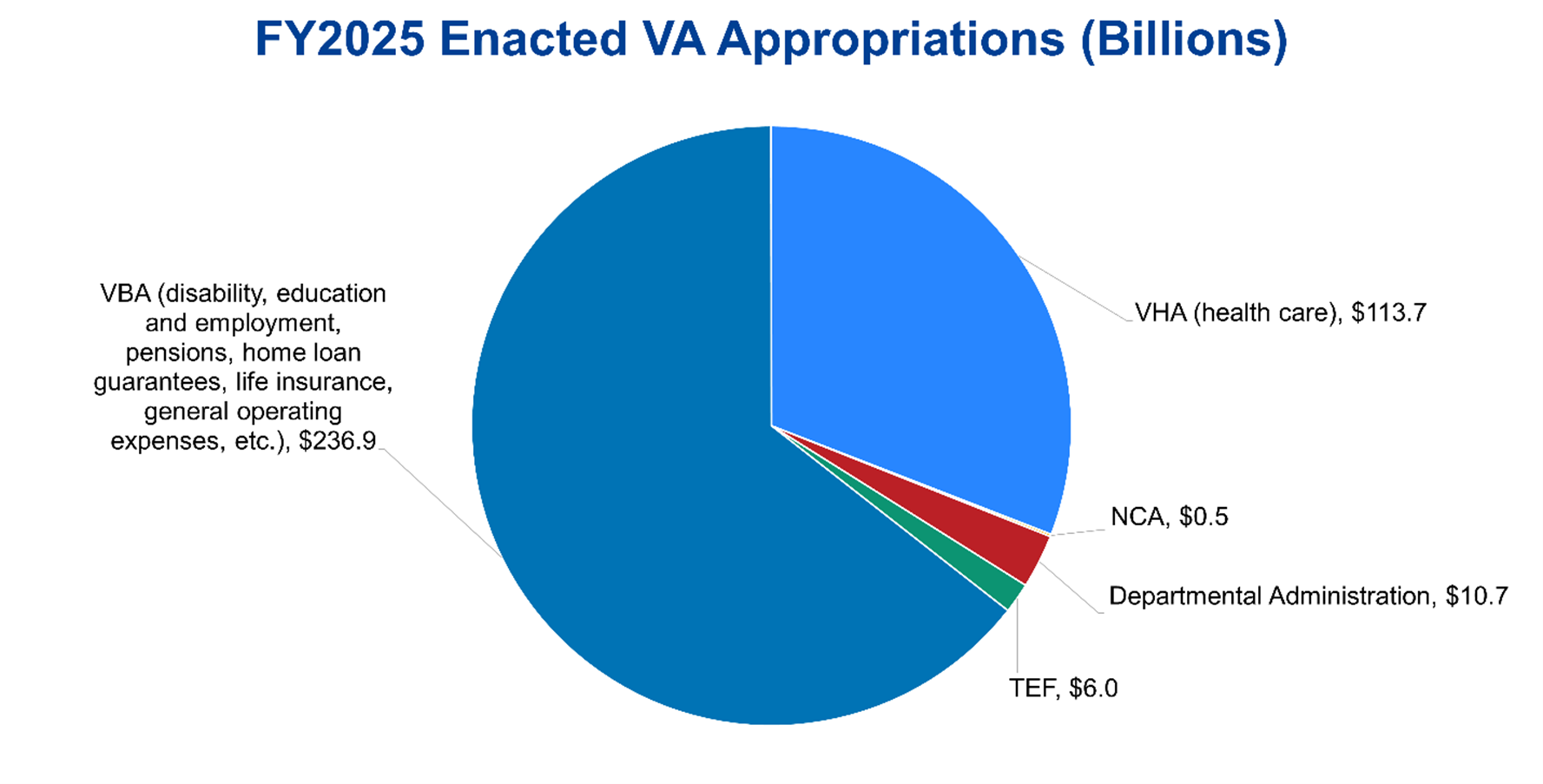

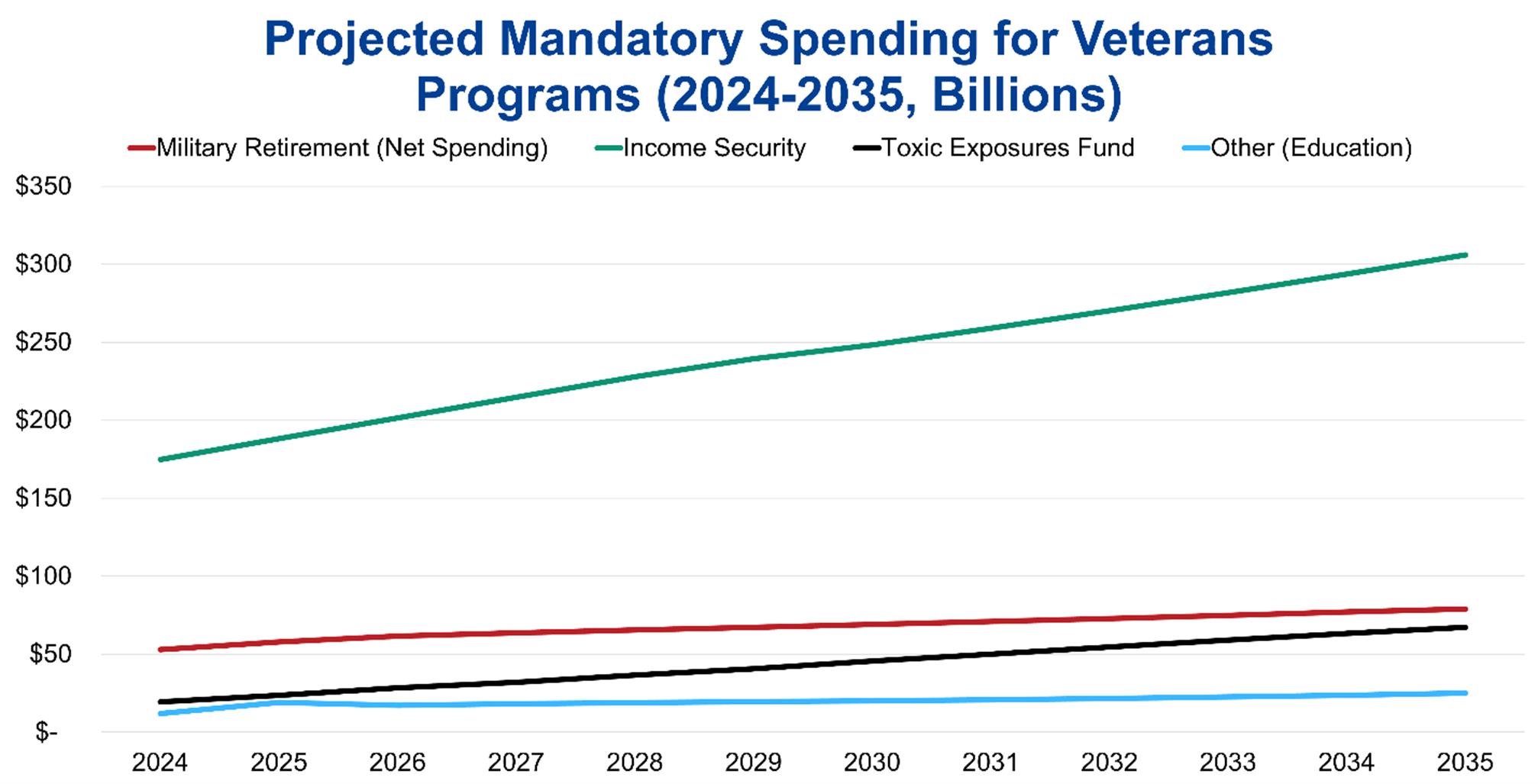

- The VA budget consists of both mandatory and discretionary spending. In FY2025, VA has a total budget of $368 billion. The nonpartisan CBO estimates spending across all agencies on veterans’ programs for income security, Federal military retirement, and education benefits will increase significantly between 2024 and 2035.

- Given the rising and unsustainable national debt, Congress should consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations, which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate. Some options that Congress can consider include adjustments to VA disability compensation, eligibility for VA health care, and introducing enrollment fees and minimum out-of-pocket requirements for TRICARE.

Introduction

Under Federal law, a “veteran” is defined as a person who served in the active military, naval, air, or space service and who was discharged or released under conditions other than dishonorable, as defined in 38 U.S.C. § 101(2). Active-duty personnel serve in the military full-time and can be deployed at any time, for any length of time. Veterans who were active duty servicemembers are eligible for the full suite of veterans’ programs discussed below. Members of the military can also serve in the reserves and National Guard, which are typically part-time commitments with drill and training requirements. The reserves are under the control of the Federal government while the National Guard reports to both a state Governor and the President. In addition to national security and wartime responsibilities, members of the National Guard also respond to state and local emergencies and natural disasters. Servicemembers in the reserves and National Guard may be eligible for the full or modified benefits and services described here depending on how much active-duty service time they have under Federal orders, among other criteria. National Guard members are also eligible for state government benefits that vary by state to recognize their state-level role.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the primary Federal agency that provides benefits and services to veterans who meet eligibility criteria, including hospital and medical care, disability compensation, pensions, education, vocational rehabilitation and employment services, life insurance and home loan guarantees, and death benefits that cover burial expenses. VA’s three administrations manage the benefits and services for veterans: the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) administers health care services and medical and prosthetic research programs; the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) provides compensation, pensions, and education assistance; and the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) is responsible for maintaining national veterans cemeteries, providing grants to states and other entities for operating and improving state veterans cemeteries, and providing memorial benefits. The Board of Veterans Appeals is responsible for reviewing all appeals made by veterans or their representatives for eligibility for veterans' benefits. Appeals from the Board are heard by the US Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims.

Veterans may also be eligible to receive TRICARE—the uniformed services health care program for active duty, National Guard, and Reserve members, retirees, survivors, and their families—based on their retirement from the military and other eligibility criteria and may qualify for a military pension after retirement from the military depending on years of service and other criteria. TRICARE combines the Military Health System with a network of civilian health care professionals, including private health systems, to provide health care to eligible recipients, while the Defense Finance and Accounting Service for the Department of Defense establishes and maintains pay for retired servicemembers.

Brief History of Veterans’ Programs

Since the earliest days of the United States, colonies and states have supported disabled service members, widows, and orphans. After independence, the Federal government established the Pension Bureau within the War Department to administer Revolutionary War pensions. The Pension Bureau moved to the Department of the Interior in 1849. In 1865, Congress established the National Homes for Volunteer Disabled Soldiers, providing long-term housing and care across regional campuses, which became the model for today’s VA medical system. After the Civil War, the Federal government continued to implement various programs for veterans tied to medical innovations, vocational training, educational support, home ownership programs, and national memorials.

Following World War I, multiple veterans’ services (disability compensation, insurance, and vocational rehabilitation) were consolidated under the Veterans Bureau in 1921, increasing access to services nationwide. In 1930, President Hoover continued this consolidation by issuing Executive Order 5398, which established the Veterans Administration as an independent agency in the Executive Branch by uniting the Veterans Bureau, the Pension Bureau, and the National Homes program. The expansion of the military during World War II, the passage of the GI Bill in 1944, and the expanded medical infrastructure mandated by the Department of Medicine and Surgery Act in 1946 modernized the Veterans Administration health care system and expanded its role in research, training, and supporting veterans. Congress established the VHA in 1946 and the NCA within VA in 1973, while the VBA was established after an internal reorganization in 1953, to align with the larger presence of the US military and veterans in society. Finally, President Reagan signed legislation in 1988 converting the Veterans Administration to the Cabinet-level Department of Veterans Affairs, which became effective in 1989. Today, VA ranks second only to the Defense Department in terms of both employee headcount and operational budget.

Overview of Programs for Veterans

VA administers most benefits and services for veterans, including health care, disability benefits, education and employment programs, and pensions, among other benefits. VA also provides benefits to the families and caregivers of veterans.

VA Health Care

VHA is tasked with delivering health care to eligible veterans. VHA is also responsible for conducting medical research, training clinicians, and serving as a contingency backup to the Defense Department medical system during a national security emergency, demonstrating the VHA’s mission to both deliver health care and participate in broader emergency readiness. VHA operates as the largest public, integrated direct care system in the US, encompassing over 1,200 medical centers, outpatient clinics, and long-term care facilities, organized across regional Veterans Integrated Service Networks. VHA primarily provides care directly rather than functioning as an insurer, though VHA can arrange community care via the Community Care Network when VA services are inaccessible or when this is in the veteran’s best medical interest. Congress also authorized the VHA to bill insurers and some veterans for non-service-connected care to help offset costs.

Eligibility for VA health care is not universal but has expanded over time in the Veterans’ Health Care Eligibility Reform Act of 1996 and the PACT Act of 2022; the latter established the Toxic Exposure Fund (TEF) for health care and research related to environmental hazards, provided expanded access for veterans exposed to burn pits and toxins, and added new presumptive conditions for Agent Orange exposure for Vietnam-era veterans. Enrollment is organized into one of eight priority groups, and copay requirements depend on income, disability status, and service history. Certain veterans—those with service-connected disabilities, Medal of Honor or Purple Heart recipients, and former POWs—are in the highest priority groups and receive care without premiums, deductibles, or coinsurance. Once enrolled, veterans remain in the system without needing to reapply, providing them with a reliable safety net.

Veterans enrolled in VA health care have access to a core set of benefits and services, including preventive care, treatments for injuries and illnesses, functional improvement support, and quality-of-life enhancements. Preventive services consist of health exams, nutrition education, immunizations, and genetic disease counseling. Emergency and urgent care services are available within VA facilities or through contracted providers such as walk?in retail clinics, though accessing non?VA emergency care for non-service-connected conditions depends on meeting the following VA criteria: veterans must be enrolled, have seen VA care in the past 24 months, and inform the urgent care provider of their VA benefit usage.

Beyond direct medical care, VA benefits extend to critical support services, such as mental health care for service-connected conditions including PTSD, sexual trauma, depression, and substance use, along with assisted living or home health care based on need and availability. Veterans can also access prescriptions, ancillary services (such as diagnostic testing, physical and vision rehabilitation, prosthetics, audiology, and radiation oncology), and non-medical services (such as travel reimbursements, caregiver support, and transportation assistance). Additionally, patient advocates are available to facilitate language services and smooth access to benefits.

Some veterans may receive additional benefits, such as dental coverage, based on their priority group, provider recommendations, and relevant medical standards. VA health care currently excludes certain services, such as cosmetic surgery (unless medically necessary), gender-affirming surgery, health-spa memberships, and non-FDA-approved treatments (unless part of a clinical trial or under compassionate use). VA has a National Formulary listing the drugs and supplies generally covered under VA pharmacy benefits (often supplied through private pharmacies in the network), and prescription coverage from non-VA community providers is possible after meeting specified criteria (enrollment in VA health care, having an assigned VA primary care provider, submission of medical records, and provider agreement). Eligibility and potential out-of-pocket costs depend on income level, disability rating, and military service history. Most veterans must complete a financial assessment during enrollment to determine copay requirements.

Veterans who completed a minimum of 20 years or more of active-duty service are entitled to additional benefits outside of VA. One of those benefits is health care coverage through TRICARE. Retired members of the Armed Forces are eligible for TRICARE Prime, TRICARE Select, and TRICARE for Life. Those who retire from the reserves or National Guard may qualify for TRICARE Retired Reserve when they are under age 60; when they turn 60, these members of the military are eligible for the same TRICARE benefits as all other retired servicemembers. Veterans may also be eligible for these TRICARE benefits if they are on the Temporary Disabled Retirement List (TDRL) or Permanent Disability Retirement List (PDRL). Placement on the TDRL requires a physical condition, injury, or disease that renders a service member unfit for military service and a disability rating of at least 30% (separate from the rating given by VA). Service members are then periodically reevaluated every 18 months for up to five years, after which they may be placed on the PDRL.

VA Disability Benefits

VBA administers the Veterans Disability Compensation (VDC) program, which provides a monthly, tax?free cash benefit to veterans who have disabilities that VA determines to be service?connected, meaning conditions that were “incurred or aggravated” during active military service. To qualify for VA disability compensation, veterans must have a current physical or mental condition that was caused or worsened by active military service, and veterans must have served on active duty or related military training. Veterans must also demonstrate a link between their medical condition and service, whether it arose during service, arose before and was aggravated by service, or manifested afterward (post?service). Certain “presumptive” conditions—such as those that developed within one year of discharge, were caused by exposure to toxic substances, or resulted from being a POW—are automatically deemed to be service-connected. Discharge type is crucial as those who received a dishonorable discharge may be ineligible.

The amount of compensation a veteran may receive depends on the veteran’s disability rating, which ranges from 0% to 100% in 10% increments and is based on criteria outlined in the VA Schedule for Rating Disabilities. To qualify for VDC, a veteran must have a disability that meets or exceeds a 10% VA disability rating. For veterans with a 30% or higher rating, the monthly benefit amount may be increased for veterans with a spouse or dependents. Veterans with higher disability ratings are eligible for correspondingly larger compensation amounts. The compensation is intended to support veterans whose service?connected disabilities impact their quality of life, and the program serves as one of the primary direct financial benefits provided through the VA to mitigate service?related impairments.

VA Education and Employment Programs

Established in 1944, one of the major educational programs for veterans is the GI Bill, which provides educational support to qualifying veterans and their families, helping to cover tuition, fees, and training-related expenses. On or after September 11, 2001, service members who have served at least 90 days on active duty, received a Purple Heart, or served for at least 30 continuous days and were honorably discharged with a service-connected disability are eligible for Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits (Chapter 33). These benefits include tuition and fees, funding for housing, money for books and supplies, tutorial assistance, work study, and licensing and certification tests and prep courses. Veterans may also qualify for the Montgomery GI Bill Active Duty program if they have served at least two years, or for the Selected Reserve program if they are a reservist or Guard member meeting specified requirements. Spouses, dependents, and other family members may be eligible for education benefits as well.

Another crucial career-related program for veterans is Veteran Readiness and Employment (VR&E), formerly known as Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment, which offers support to eligible service members and veterans with service-connected disabilities that impair their ability to work. VBA administers this program designed to enable veterans to become employable and sustain suitable employment; and for those unable to work, to provide independent living services that foster maximum quality of life. Eligibility requires a discharge under conditions other than dishonorable, and either at least a 20% disability rating combined with an employment handicap (defined as impairment of a veteran or servicemember’s ability to prepare for, obtain, or retain employment consistent with his or her abilities, aptitudes, and interests) or a 10% disability rating with a serious employment handicap.

VR&E (also referred to as Chapter 31) helps participants explore employment options, navigate education or training needs, and in certain cases, supports family members who may qualify for benefits. VR&E support is organized into five distinct tracks tailored to specific career or life circumstances: Reemployment, Rapid Access to Employment, Self?Employment, Employment through Long?Term Services, and Independent Living (veterans may transition between tracks if needed).

To access VR&E services, applicants must apply regardless of whether they have received a VA disability rating. Upon applying, veterans are paired with a Vocational Rehabilitation Counselor (VRC) who conducts a holistic evaluation, assesses their eligibility and employment handicap, and collaborates with them to develop a personalized rehabilitation plan. This plan outlines the specific VR&E track and services suited to the individual's skillset and goals, ranging from reemployment and job training to business development and independent living support. The VRC then provides ongoing guidance, including tutorial assistance, job-readiness training, and referrals to other resources to help veterans execute their plan effectively. While services may be provided directly by the VA, they are often outsourced; benefits typically span up to 48 months, with potential extensions. Additionally, participants may receive subsistence allowances and loans.

Pensions for Veterans and Retired Members of the Armed Forces

VBA also manages three pension programs that provide monthly financial support to wartime veterans (those who served during declared periods of conflict such as the Vietnam era) who meet specific age or disability criteria and certain income and net worth limits. The Veterans Pension and Survivors Pension are needs-based and designed for wartime veterans or their surviving spouses and dependent children with limited income and net worth. The Medal of Honor Pension is not tied to income and is solely for recipients of that honor (only about 70 living recipients are eligible).

To be eligible for the Veterans Pension, a veteran must not have received a dishonorable discharge and their annual family income and net worth (including a spouse’s assets but excluding home, vehicle, and most furnishings) must stay below thresholds established by Congress and VA (a net worth limit of roughly $155,000 in 2024 coupled with a 36-month lookback period and five-year penalty period for transferring assets). Service requirements include at least one day of active duty during a recognized wartime period and sufficient total active-duty service tied to enlistment date and status (e.g., at least 90 days before September 8, 1980, or at least 24 months for those enlisting later). Wartime periods recognized for eligibility include the Mexican Border, World War?I, World War?II, the Korean Conflict, two Vietnam-era ranges, and the Gulf War (ongoing as law or Presidential proclamation dictates). Additionally, veterans must satisfy at least one of the following conditions: be 65 years or older, have a permanent and total disability, be a nursing home patient due to disability, or receive Social Security Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income. Dependents (e.g., a spouse, minor child, child in school, or adult child incapable of self-support) can increase a veteran’s pension amount.

Congress sets the maximum annual pension rates for the Veterans and Survivors Pensions, which vary based on aid and attendance benefits, housebound benefits, and the number of dependents in a

household. In 2024, the maximum annual pension amounts for the Veterans Pension were between $16,551 and $32,729 and the amounts for the Survivors Pension were between $11,102 and $21,166. In FY2023, the Veterans Pension paid out an average annual benefit of approximately $14,211 to about 153,000 beneficiaries, totaling around $2.18 billion in payouts. The Survivors Pension provided an average benefit of $10,772 to about 110,000 beneficiaries, totaling roughly $1.18 billion for that year.

For eligible active duty personnel with a minimum of 20 years of active service, the Defense Department provides a military pension, with eligibility depending on the retirement plan for which a veteran qualifies. Active-duty personnel are placed under either the Legacy or High-36 Retirement System (if they joined before January?1,?2006) or the Blended Retirement System (BRS) (for those who joined after December?31,?2017). Veterans who entered service between 2006 and 2017 have the option to choose either system. Both plans calculate retirement pay based on an average of the highest 36 months of basic pay. The BRS also includes employer matching contributions to the Thrift Savings Plan (up to 4%), whereas the legacy system does not.

Reserve service members typically become eligible for pension benefits after accruing 20 years of qualifying service (calculated based on points tied to days of active service, years served, and the completion of training and specified accredited courses), but payments usually only begin at age 60 unless they have spent significant time on active duty. Importantly, these benefits will not start automatically; eligible reservists must actively request their retirement benefits through the servicing military department. Service members who become disabled—specifically those with at least a 30% disability—may qualify for disability retirement (Chapter 61), even if they have fewer than 20 years of service or retired early under the Temporary Early Retirement Act. This option offers a pathway to retirement benefits based on disability rather than years served.

Other VA Benefits (Home Loans, Life Insurance, Family and Caregiver Benefits)

VA offers a variety of home loan programs designed to help veterans, service members, and eligible surviving spouses buy, build, improve, or refinance a home. One option is the VA Direct Home Loan, where VA itself acts as the mortgage lender, often offering terms that are more favorable than those available from private lenders. The other three are VA?backed loans, where private lenders issue the loan with the VA guaranteeing a portion of it, reducing lender risk and frequently enabling veterans to secure loans with no down payment and better interest rates and loan terms. The available VA?backed loan options include: purchase loans for buying, building, or improving a home, often without a down payment; Interest Rate Reduction Refinance Loans (IRRRLs), also known as streamline refinances, for reducing monthly payments or shifting to a fixed-rate mortgage; and Cash?Out Refinance Loans, which allow a veteran to tap into their home equity to pay off debt, fund education, or cover other expenses.

VA also provides several life insurance programs designed to support service members, veterans, and their families. These include Servicemembers’ Group Life Insurance (SGLI) for active-duty personnel, which automatically offers low-cost term coverage (up to $500,000) with options also available for family members (FSGLI) and traumatic injury protection (TSGLI). Upon separation, eligible individuals can convert their SGLI into Veterans’ Group Life Insurance (VGLI)—a renewable term policy—if applied for within 1 year and 120 days, with relaxed health requirements when applied within 240 days. Veterans with service-connected disabilities (including 0% ratings) may be eligible for Veterans Affairs Life Insurance (VALife), a guaranteed acceptance whole life policy with coverage up to $40,000, no requirement to answer medical questions, and a two-year waiting period before full benefits commence.

Additionally, VA offers a range of benefits to spouses, dependents, survivors, and caregivers of veterans. Family members may be eligible for health care through CHAMPVA, life insurance options, education benefits, and survivors’ compensation, depending on their relationship to the veteran and their individual circumstances. Survivors may qualify for burial assistance and monetary benefits like Dependency and Indemnity Compensation (DIC), along with burial support services. Additionally, educational programs such as Survivors’ and Dependents’ Education Assistance (DEA, also known as Chapter?35) and the Fry Scholarship help with tuition, fees, and supplies.

Caregivers to veterans, such as spouses or other close family members, can access specialized Caregiver Support Programs. The Program of General Caregiver Support Services (PGCSS) offers broad assistance including training, peer mentoring, coaching, respite care, and access to VA and community resources. For caregivers of veterans with serious, service?connected conditions rated 70% or higher, the Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) provides more intensive support, including education, mental health counseling, respite care, travel benefits, health care via CHAMPVA if uninsured, and a monthly stipend.

Funding for Veterans’ Programs

VA’s programs consist of both discretionary spending, which is subject to appropriations by Congress, and mandatory spending. VA’s mandatory spending includes disability compensation for veterans, DIC, pensions, VR&E, education programs, life insurance, and housing programs, among others. These entitlements are included in Congressional appropriations bills, though the funding levels are determined by statutory formulas. VA’s discretionary appropriations fund medical care, medical research, construction programs, IT, and other general operating expenses. VA has advanced appropriation authority for certain medical care and benefit accounts, which means that funds appropriated in one fiscal year are available to spend in future fiscal years.

The Department’s total budget in FY2024 was approximately $310 billion, of which $175 billion was mandatory spending and $135 billion was discretionary. The VBA received roughly $180 billion in funding and the VHA $120 billion, with $480 million for the NCA and $10 billion for departmental administration. For FY2025, Congress passed a full-year continuing resolution, generally holding discretionary spending flat across most of the Federal government. While total discretionary funding for VA fell to $129 billion, mandatory spending for VA increased by more than 35% to nearly $240 billion, for a total budget of $368 billion in FY2025. The increased mandatory funding in FY2025 was largely allocated to the VBA ($237 billion in total funding) and Congress also included $6 billion for the Cost of War Toxic Exposure Fund (TEF), which funds health care, claims processing, and other expenses related to providing care to veterans exposed to toxic substances.

Figure 1: Breakdown of FY2025 Enacted Funding for VA

Sources: Department of Veterans Affairs FY2025 Appropriations, Congressional Research Service, July 24, 2025; The Conference Board, 2025.

The nonpartisan CBO also makes 10-year projections for certain mandatory spending categories affecting veterans: income security (veterans’ compensation, pensions, and life insurance programs), TEF, Federal military retirement, and “other” (primarily GI Bill and similar education benefits). Between 2024 and 2035, CBO estimates spending on veterans’ income security programs will grow from $175 billion to $306 billion, TEF expenditures will grow from $19 billion to $67 billion, and education and other spending will increase from $12 billion to $25 billion. Including offsetting receipts, military retirement spending is projected to increase from $53 billion in 2024 to $79 billion in 2035.

Figure 2: CBO Projections of Certain Mandatory Spending Affecting Veterans (2024-2035)

Sources: The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035, Congressional Budget Office, January 2025; The Conference Board, 2025.

Impact of Veterans’ Programs

Based on 2023 data, VA estimates there are approximately 17.6 million living veterans in the US (VA uses a deterministic population projection model blending various VA and American Community Survey data sources because VA’s administrative data for older veterans is limited). In 2023, more than 40% of living veterans served in the Gulf War era (since 1990), 30% served during the Vietnam War, and 5% served in the Korean War and WWII. Roughly 80% of living veterans served during wartime. In FY2024, VA provided 127.5 million health care appointments, delivered $187 billion in benefits to 6.7 million veterans and survivors, and processed more than 2.5 million disability benefit claims. Among veterans, trust in VA reached 80% in 2024, up from 55% in 2016 (the first time VA conducted the survey). Veteran trust in VA health care was also more than 90% last year. Among Americans overall, 56% of respondents in a 2023 survey had a favorable opinion of VA, with similar shares of Republicans and Democrats holding favorable views. Nearly 80% of Americans also have broad confidence in the military to act in the public’s best interests, demonstrating the overall favorable opinion that the US population has of the Nation’s military and its veterans.

Opportunities for Reform to Address Long-Term Fiscal Challenges

The Federal government’s rising spending on VA’s budget and other programs for veterans comes in the context of the unsustainable US national debt, which recently reached a record $36.7 trillion. Government spending also exceeded government revenues by $1.9 trillion in FY2024. To finance this increasing spending, the Federal government will continue issuing debt in the form of Treasury securities, which will in turn increase the costs of servicing the national debt and begin crowding out other spending priorities, which could include the discretionary portion of spending on veterans. As such, Congress can consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations, which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate. Congress should also protect vulnerable populations of veterans, their families, and other stakeholders by gradually phasing in any legislative changes to provide beneficiaries sufficient time to adjust.

CBO, the nonpartisan agency that produces independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional budget process, has described several options that would produce large reductions to the deficit (each option would require a statutory change). Policymakers should consider the tradeoffs from these policies to balance the decreases in spending with the reductions in coverage and benefits under the affected veterans’ programs.

The first set of options concerns VA disability compensation. One option would be to means test eligibility for VA disability compensation, restricting benefits for veterans with total household income above $135,000 (corresponds to the 70th percentile of total household income in the US) by decreasing disability compensation by one dollar for every two dollars of gross household income above the threshold, generating a deficit reduction of $384 billion over 10 years. Another option would limit Individual Unemployability (IU) payments for veterans age 67 or older, which is the full retirement age for Social Security benefits for those born after 1959. These IU payments are supplemental compensation for veterans who have a disability rating of between 60 and 90 percent and VA determines cannot maintain substantial gainful employment due to the service-connected disability. Eliminating IU payments for all veterans 67 or older would reduce the deficit by over $60 billion over 10 years, while ending these payments for prospective applicants starting in December 2025 would reduce the deficit by $13.5 billion over 10 years. A third option would reduce disability compensation payments by 30 percent at age 67 for all veterans who start receiving disability compensation in 2026 or later, which CBO projects reduces the deficit by almost $34 billion over 10 years (veterans who already collect disability compensation would see no change). A fourth option would require disability ratings of 30 percent or higher for VA disability compensation (CBO estimates about 20 percent of veterans have a disability rating below 30 percent). Narrowing eligibility for all veterans would reduce the deficit by almost $60 billion over 10 years, while restricting eligibility for new applicants would reduce the deficit by approximately $11 billion over the next decade. Finally, Congress could include VA’s disability benefit payments in taxable income, decreasing the deficit by nearly $235 billion over 10 years due to higher tax revenue; this option is controversial as disability benefits are compensation for injury and a veteran’s sacrifice, not earned income that the Federal government typically taxes.

The next set of options concerns health care for veterans and the active-duty military (as changes for TRICARE would also affect active-duty servicemembers). One option would end enrollment in VA’s health care system for all veterans in priority groups 7 and 8 (about 1 million veterans in 2023), reducing the deficit by approximately $60 billion over 10 years. Some of these veterans would be eligible for Medicare, increasing mandatory spending on that program and thus lowering the net deficit reduction to about $30 billion over the next decade. Two additional options concern TRICARE. Beneficiaries eligible for TRICARE are automatically enrolled in TRICARE for Life (TFL) when they become eligible for Medicare, with TFL paying nearly all medical costs not covered by Medicare for no enrollment fee. About 2.5 million people are currently enrolled in TFL. Charging an enrollment fee for TFL (set to match the fees for the preferred-provider plan in TRICARE paid by retirees who were not yet eligible for Medicare and who entered service after 2017, or about $610 for individual coverage and $1,220 for family coverage in 2027) would produce an estimated net reduction in the deficit of $17 billion over 10 years. Introducing minimum out-of-pocket requirements for TFL, specifically by implementing a deductible of $850 and cost sharing of 50 percent of the next $7,650 (thresholds comparable to certain high deductible private Medigap plans), would reduce the deficit by more than $30 billion over 10 years. The thresholds for both options would grow by the same rate as average Medicare costs in later years.

An alternative delivery system for veterans’ health care benefits is enrolling veterans in Medicare instead of the VHA. A 2016 analysis found that providing a full Medicare Part A, Part B, and Part D benefit as well as Part D deductibles and a typical Medigap policy would cost less than VHA medical care funding. The prospective savings from this alternative delivery of health care would have to be balanced with the administrative burden of selling VHA assets and the unemployment and economic effects of downsizing the significant VHA workforce. Other potential health care reforms include increasing access to VA community care, particularly to address mental health conditions and addiction and promote continuity of care. While VA community care has the potential to reduce barriers to access and long wait times for appointments, the cost and quality of community care compared to VHA-delivered care is still largely unknown, meriting further research. Finally, VA is deploying the Federal Electronic Health Record system in VA medical centers and associated clinics across the country, allowing clinicians to access a veteran’s full medical history in one location easily.

Regarding the programs VBA manages, VA has undertaken several initiatives to modernize benefits delivery and promote digital transformation. VA has established an online platform to access and manage VA education benefits, launched a disability compensation claim tool to facilitate the submission of claims, and implemented an online debt management tool as a central location to access and manage a veteran’s debt information. VA is also focusing on improving the DIC claims process for survivors and dependents of deceased veterans. In 2025, Congress passed and the President signed the VA Home Loan Program and Reform Act, which authorizes VA to take certain actions in cases of default on home loans under the VA home loan program and establishes a partial claim program on VA loans for primary residences that are in default or at imminent risk of default. These new operational and legislative efforts must be considered in light of the reduction of staff within the VA, estimated to be nearly 30,000 employees by the end of FY2025.

Conclusion

VA and other veterans’ programs are crucial supports for veterans, providing health care, disability compensation, education and employment supports, pensions, and other benefits, honoring the promise the Nation has made to our veterans. In the context of the Federal government’s deteriorating fiscal position and unsustainable national debt, Congress must holistically evaluate opportunities for reform throughout the Federal government and address these negative fiscal trends quickly to allow for adequate time to phase in changes to VA and other veterans’ programs. The longer the delays, the greater the chance that necessary legislative changes to preserve veterans’ benefits will be disruptive to veterans, their families, and their communities.

For Further Reading

- CED’s Explainer, US National Debt, August 2025

- CED’s Explainer, Social Security, August 2025

- CED’s Explainer, Medicare, August 2025

- CED’s Explainer, Medicaid, August 2025

- CED’s Solutions Brief, Modernizing Health Programs for Fiscal Sustainability and Quality, November 18, 2024

- CED’s Solutions Brief, Debt Matters: A Road Map for Reducing the Outsized US Debt Burden, February 9, 2023

- “The Debt Crisis is Here,” Dana M. Peterson and Lori Esposito Murray, November 13, 2023

Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and other agencies operating programs benefiting veterans and their families fulfill a national promise to veterans. These programs offer important benefits and services, providing health care, disability compensation, education and employment support, pensions, and other benefits to veterans. However, it is also important to consider the fiscal context: because the US national debt has recently reached a record $36.7 billion and government spending exceeded government revenues by $1.9 trillion in Fiscal Year (FY) 2024, this threatens the fiscal foundation that supports veterans’ programs and other vital government services. As a significant component of Federal spending, programs for veterans must be considered as part of a holistic evaluation of the Federal government’s fiscal position to reverse its negative trajectory while fully honoring our national promise to veterans and ensuring they receive the benefits to which they are entitled. Indeed, only through setting the country on a sounder fiscal footing will the US be able to maintain the levels of spending it has promised to veterans and the quality of care they receive.

This Explainer provides a brief history of veterans’ programs; an overview of health care, disability benefits, education and employment programs, pensions, and other benefits for veterans; a description of funding for veterans’ programs; the impact of veterans’ programs; and a discussion of some options prepared by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) for reforms to veterans’ programs that would serve to reduce the national debt.

- The VA is the primary Federal government agency that provides benefits and services to veterans. Veterans may also be eligible to obtain TRICARE and a military pension from the Department of Defense.

- Support for veterans and their survivors has a long tradition, with a variety of health care, housing, disability payment, and pension programs emerging after periods of war. Eventually, these programs were consolidated in 1930 under the Veterans Administration. Legislation in 1988 established the current VA in the Cabinet.

- The Veterans Health Administration provides health care (often directly) to eligible veterans, including preventive care, treatments for injuries and illnesses, functional improvement support, quality-of-life enhancements, and other critical support services.

- The Veterans Benefits Administration offers disability compensation benefits, education and employment programs, pensions, home loan guarantees, life insurance, and family and caregiver benefits.

- The VA budget consists of both mandatory and discretionary spending. In FY2025, VA has a total budget of $368 billion. The nonpartisan CBO estimates spending across all agencies on veterans’ programs for income security, Federal military retirement, and education benefits will increase significantly between 2024 and 2035.

- Given the rising and unsustainable national debt, Congress should consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations, which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate. Some options that Congress can consider include adjustments to VA disability compensation, eligibility for VA health care, and introducing enrollment fees and minimum out-of-pocket requirements for TRICARE.

Introduction

Under Federal law, a “veteran” is defined as a person who served in the active military, naval, air, or space service and who was discharged or released under conditions other than dishonorable, as defined in 38 U.S.C. § 101(2). Active-duty personnel serve in the military full-time and can be deployed at any time, for any length of time. Veterans who were active duty servicemembers are eligible for the full suite of veterans’ programs discussed below. Members of the military can also serve in the reserves and National Guard, which are typically part-time commitments with drill and training requirements. The reserves are under the control of the Federal government while the National Guard reports to both a state Governor and the President. In addition to national security and wartime responsibilities, members of the National Guard also respond to state and local emergencies and natural disasters. Servicemembers in the reserves and National Guard may be eligible for the full or modified benefits and services described here depending on how much active-duty service time they have under Federal orders, among other criteria. National Guard members are also eligible for state government benefits that vary by state to recognize their state-level role.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the primary Federal agency that provides benefits and services to veterans who meet eligibility criteria, including hospital and medical care, disability compensation, pensions, education, vocational rehabilitation and employment services, life insurance and home loan guarantees, and death benefits that cover burial expenses. VA’s three administrations manage the benefits and services for veterans: the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) administers health care services and medical and prosthetic research programs; the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) provides compensation, pensions, and education assistance; and the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) is responsible for maintaining national veterans cemeteries, providing grants to states and other entities for operating and improving state veterans cemeteries, and providing memorial benefits. The Board of Veterans Appeals is responsible for reviewing all appeals made by veterans or their representatives for eligibility for veterans' benefits. Appeals from the Board are heard by the US Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims.

Veterans may also be eligible to receive TRICARE—the uniformed services health care program for active duty, National Guard, and Reserve members, retirees, survivors, and their families—based on their retirement from the military and other eligibility criteria and may qualify for a military pension after retirement from the military depending on years of service and other criteria. TRICARE combines the Military Health System with a network of civilian health care professionals, including private health systems, to provide health care to eligible recipients, while the Defense Finance and Accounting Service for the Department of Defense establishes and maintains pay for retired servicemembers.

Brief History of Veterans’ Programs

Since the earliest days of the United States, colonies and states have supported disabled service members, widows, and orphans. After independence, the Federal government established the Pension Bureau within the War Department to administer Revolutionary War pensions. The Pension Bureau moved to the Department of the Interior in 1849. In 1865, Congress established the National Homes for Volunteer Disabled Soldiers, providing long-term housing and care across regional campuses, which became the model for today’s VA medical system. After the Civil War, the Federal government continued to implement various programs for veterans tied to medical innovations, vocational training, educational support, home ownership programs, and national memorials.

Following World War I, multiple veterans’ services (disability compensation, insurance, and vocational rehabilitation) were consolidated under the Veterans Bureau in 1921, increasing access to services nationwide. In 1930, President Hoover continued this consolidation by issuing Executive Order 5398, which established the Veterans Administration as an independent agency in the Executive Branch by uniting the Veterans Bureau, the Pension Bureau, and the National Homes program. The expansion of the military during World War II, the passage of the GI Bill in 1944, and the expanded medical infrastructure mandated by the Department of Medicine and Surgery Act in 1946 modernized the Veterans Administration health care system and expanded its role in research, training, and supporting veterans. Congress established the VHA in 1946 and the NCA within VA in 1973, while the VBA was established after an internal reorganization in 1953, to align with the larger presence of the US military and veterans in society. Finally, President Reagan signed legislation in 1988 converting the Veterans Administration to the Cabinet-level Department of Veterans Affairs, which became effective in 1989. Today, VA ranks second only to the Defense Department in terms of both employee headcount and operational budget.

Overview of Programs for Veterans

VA administers most benefits and services for veterans, including health care, disability benefits, education and employment programs, and pensions, among other benefits. VA also provides benefits to the families and caregivers of veterans.

VA Health Care

VHA is tasked with delivering health care to eligible veterans. VHA is also responsible for conducting medical research, training clinicians, and serving as a contingency backup to the Defense Department medical system during a national security emergency, demonstrating the VHA’s mission to both deliver health care and participate in broader emergency readiness. VHA operates as the largest public, integrated direct care system in the US, encompassing over 1,200 medical centers, outpatient clinics, and long-term care facilities, organized across regional Veterans Integrated Service Networks. VHA primarily provides care directly rather than functioning as an insurer, though VHA can arrange community care via the Community Care Network when VA services are inaccessible or when this is in the veteran’s best medical interest. Congress also authorized the VHA to bill insurers and some veterans for non-service-connected care to help offset costs.

Eligibility for VA health care is not universal but has expanded over time in the Veterans’ Health Care Eligibility Reform Act of 1996 and the PACT Act of 2022; the latter established the Toxic Exposure Fund (TEF) for health care and research related to environmental hazards, provided expanded access for veterans exposed to burn pits and toxins, and added new presumptive conditions for Agent Orange exposure for Vietnam-era veterans. Enrollment is organized into one of eight priority groups, and copay requirements depend on income, disability status, and service history. Certain veterans—those with service-connected disabilities, Medal of Honor or Purple Heart recipients, and former POWs—are in the highest priority groups and receive care without premiums, deductibles, or coinsurance. Once enrolled, veterans remain in the system without needing to reapply, providing them with a reliable safety net.

Veterans enrolled in VA health care have access to a core set of benefits and services, including preventive care, treatments for injuries and illnesses, functional improvement support, and quality-of-life enhancements. Preventive services consist of health exams, nutrition education, immunizations, and genetic disease counseling. Emergency and urgent care services are available within VA facilities or through contracted providers such as walk?in retail clinics, though accessing non?VA emergency care for non-service-connected conditions depends on meeting the following VA criteria: veterans must be enrolled, have seen VA care in the past 24 months, and inform the urgent care provider of their VA benefit usage.

Beyond direct medical care, VA benefits extend to critical support services, such as mental health care for service-connected conditions including PTSD, sexual trauma, depression, and substance use, along with assisted living or home health care based on need and availability. Veterans can also access prescriptions, ancillary services (such as diagnostic testing, physical and vision rehabilitation, prosthetics, audiology, and radiation oncology), and non-medical services (such as travel reimbursements, caregiver support, and transportation assistance). Additionally, patient advocates are available to facilitate language services and smooth access to benefits.

Some veterans may receive additional benefits, such as dental coverage, based on their priority group, provider recommendations, and relevant medical standards. VA health care currently excludes certain services, such as cosmetic surgery (unless medically necessary), gender-affirming surgery, health-spa memberships, and non-FDA-approved treatments (unless part of a clinical trial or under compassionate use). VA has a National Formulary listing the drugs and supplies generally covered under VA pharmacy benefits (often supplied through private pharmacies in the network), and prescription coverage from non-VA community providers is possible after meeting specified criteria (enrollment in VA health care, having an assigned VA primary care provider, submission of medical records, and provider agreement). Eligibility and potential out-of-pocket costs depend on income level, disability rating, and military service history. Most veterans must complete a financial assessment during enrollment to determine copay requirements.

Veterans who completed a minimum of 20 years or more of active-duty service are entitled to additional benefits outside of VA. One of those benefits is health care coverage through TRICARE. Retired members of the Armed Forces are eligible for TRICARE Prime, TRICARE Select, and TRICARE for Life. Those who retire from the reserves or National Guard may qualify for TRICARE Retired Reserve when they are under age 60; when they turn 60, these members of the military are eligible for the same TRICARE benefits as all other retired servicemembers. Veterans may also be eligible for these TRICARE benefits if they are on the Temporary Disabled Retirement List (TDRL) or Permanent Disability Retirement List (PDRL). Placement on the TDRL requires a physical condition, injury, or disease that renders a service member unfit for military service and a disability rating of at least 30% (separate from the rating given by VA). Service members are then periodically reevaluated every 18 months for up to five years, after which they may be placed on the PDRL.

VA Disability Benefits

VBA administers the Veterans Disability Compensation (VDC) program, which provides a monthly, tax?free cash benefit to veterans who have disabilities that VA determines to be service?connected, meaning conditions that were “incurred or aggravated” during active military service. To qualify for VA disability compensation, veterans must have a current physical or mental condition that was caused or worsened by active military service, and veterans must have served on active duty or related military training. Veterans must also demonstrate a link between their medical condition and service, whether it arose during service, arose before and was aggravated by service, or manifested afterward (post?service). Certain “presumptive” conditions—such as those that developed within one year of discharge, were caused by exposure to toxic substances, or resulted from being a POW—are automatically deemed to be service-connected. Discharge type is crucial as those who received a dishonorable discharge may be ineligible.

The amount of compensation a veteran may receive depends on the veteran’s disability rating, which ranges from 0% to 100% in 10% increments and is based on criteria outlined in the VA Schedule for Rating Disabilities. To qualify for VDC, a veteran must have a disability that meets or exceeds a 10% VA disability rating. For veterans with a 30% or higher rating, the monthly benefit amount may be increased for veterans with a spouse or dependents. Veterans with higher disability ratings are eligible for correspondingly larger compensation amounts. The compensation is intended to support veterans whose service?connected disabilities impact their quality of life, and the program serves as one of the primary direct financial benefits provided through the VA to mitigate service?related impairments.

VA Education and Employment Programs

Established in 1944, one of the major educational programs for veterans is the GI Bill, which provides educational support to qualifying veterans and their families, helping to cover tuition, fees, and training-related expenses. On or after September 11, 2001, service members who have served at least 90 days on active duty, received a Purple Heart, or served for at least 30 continuous days and were honorably discharged with a service-connected disability are eligible for Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits (Chapter 33). These benefits include tuition and fees, funding for housing, money for books and supplies, tutorial assistance, work study, and licensing and certification tests and prep courses. Veterans may also qualify for the Montgomery GI Bill Active Duty program if they have served at least two years, or for the Selected Reserve program if they are a reservist or Guard member meeting specified requirements. Spouses, dependents, and other family members may be eligible for education benefits as well.

Another crucial career-related program for veterans is Veteran Readiness and Employment (VR&E), formerly known as Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment, which offers support to eligible service members and veterans with service-connected disabilities that impair their ability to work. VBA administers this program designed to enable veterans to become employable and sustain suitable employment; and for those unable to work, to provide independent living services that foster maximum quality of life. Eligibility requires a discharge under conditions other than dishonorable, and either at least a 20% disability rating combined with an employment handicap (defined as impairment of a veteran or servicemember’s ability to prepare for, obtain, or retain employment consistent with his or her abilities, aptitudes, and interests) or a 10% disability rating with a serious employment handicap.

VR&E (also referred to as Chapter 31) helps participants explore employment options, navigate education or training needs, and in certain cases, supports family members who may qualify for benefits. VR&E support is organized into five distinct tracks tailored to specific career or life circumstances: Reemployment, Rapid Access to Employment, Self?Employment, Employment through Long?Term Services, and Independent Living (veterans may transition between tracks if needed).

To access VR&E services, applicants must apply regardless of whether they have received a VA disability rating. Upon applying, veterans are paired with a Vocational Rehabilitation Counselor (VRC) who conducts a holistic evaluation, assesses their eligibility and employment handicap, and collaborates with them to develop a personalized rehabilitation plan. This plan outlines the specific VR&E track and services suited to the individual's skillset and goals, ranging from reemployment and job training to business development and independent living support. The VRC then provides ongoing guidance, including tutorial assistance, job-readiness training, and referrals to other resources to help veterans execute their plan effectively. While services may be provided directly by the VA, they are often outsourced; benefits typically span up to 48 months, with potential extensions. Additionally, participants may receive subsistence allowances and loans.

Pensions for Veterans and Retired Members of the Armed Forces

VBA also manages three pension programs that provide monthly financial support to wartime veterans (those who served during declared periods of conflict such as the Vietnam era) who meet specific age or disability criteria and certain income and net worth limits. The Veterans Pension and Survivors Pension are needs-based and designed for wartime veterans or their surviving spouses and dependent children with limited income and net worth. The Medal of Honor Pension is not tied to income and is solely for recipients of that honor (only about 70 living recipients are eligible).

To be eligible for the Veterans Pension, a veteran must not have received a dishonorable discharge and their annual family income and net worth (including a spouse’s assets but excluding home, vehicle, and most furnishings) must stay below thresholds established by Congress and VA (a net worth limit of roughly $155,000 in 2024 coupled with a 36-month lookback period and five-year penalty period for transferring assets). Service requirements include at least one day of active duty during a recognized wartime period and sufficient total active-duty service tied to enlistment date and status (e.g., at least 90 days before September 8, 1980, or at least 24 months for those enlisting later). Wartime periods recognized for eligibility include the Mexican Border, World War?I, World War?II, the Korean Conflict, two Vietnam-era ranges, and the Gulf War (ongoing as law or Presidential proclamation dictates). Additionally, veterans must satisfy at least one of the following conditions: be 65 years or older, have a permanent and total disability, be a nursing home patient due to disability, or receive Social Security Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income. Dependents (e.g., a spouse, minor child, child in school, or adult child incapable of self-support) can increase a veteran’s pension amount.

Congress sets the maximum annual pension rates for the Veterans and Survivors Pensions, which vary based on aid and attendance benefits, housebound benefits, and the number of dependents in a

household. In 2024, the maximum annual pension amounts for the Veterans Pension were between $16,551 and $32,729 and the amounts for the Survivors Pension were between $11,102 and $21,166. In FY2023, the Veterans Pension paid out an average annual benefit of approximately $14,211 to about 153,000 beneficiaries, totaling around $2.18 billion in payouts. The Survivors Pension provided an average benefit of $10,772 to about 110,000 beneficiaries, totaling roughly $1.18 billion for that year.

For eligible active duty personnel with a minimum of 20 years of active service, the Defense Department provides a military pension, with eligibility depending on the retirement plan for which a veteran qualifies. Active-duty personnel are placed under either the Legacy or High-36 Retirement System (if they joined before January?1,?2006) or the Blended Retirement System (BRS) (for those who joined after December?31,?2017). Veterans who entered service between 2006 and 2017 have the option to choose either system. Both plans calculate retirement pay based on an average of the highest 36 months of basic pay. The BRS also includes employer matching contributions to the Thrift Savings Plan (up to 4%), whereas the legacy system does not.

Reserve service members typically become eligible for pension benefits after accruing 20 years of qualifying service (calculated based on points tied to days of active service, years served, and the completion of training and specified accredited courses), but payments usually only begin at age 60 unless they have spent significant time on active duty. Importantly, these benefits will not start automatically; eligible reservists must actively request their retirement benefits through the servicing military department. Service members who become disabled—specifically those with at least a 30% disability—may qualify for disability retirement (Chapter 61), even if they have fewer than 20 years of service or retired early under the Temporary Early Retirement Act. This option offers a pathway to retirement benefits based on disability rather than years served.

Other VA Benefits (Home Loans, Life Insurance, Family and Caregiver Benefits)

VA offers a variety of home loan programs designed to help veterans, service members, and eligible surviving spouses buy, build, improve, or refinance a home. One option is the VA Direct Home Loan, where VA itself acts as the mortgage lender, often offering terms that are more favorable than those available from private lenders. The other three are VA?backed loans, where private lenders issue the loan with the VA guaranteeing a portion of it, reducing lender risk and frequently enabling veterans to secure loans with no down payment and better interest rates and loan terms. The available VA?backed loan options include: purchase loans for buying, building, or improving a home, often without a down payment; Interest Rate Reduction Refinance Loans (IRRRLs), also known as streamline refinances, for reducing monthly payments or shifting to a fixed-rate mortgage; and Cash?Out Refinance Loans, which allow a veteran to tap into their home equity to pay off debt, fund education, or cover other expenses.

VA also provides several life insurance programs designed to support service members, veterans, and their families. These include Servicemembers’ Group Life Insurance (SGLI) for active-duty personnel, which automatically offers low-cost term coverage (up to $500,000) with options also available for family members (FSGLI) and traumatic injury protection (TSGLI). Upon separation, eligible individuals can convert their SGLI into Veterans’ Group Life Insurance (VGLI)—a renewable term policy—if applied for within 1 year and 120 days, with relaxed health requirements when applied within 240 days. Veterans with service-connected disabilities (including 0% ratings) may be eligible for Veterans Affairs Life Insurance (VALife), a guaranteed acceptance whole life policy with coverage up to $40,000, no requirement to answer medical questions, and a two-year waiting period before full benefits commence.

Additionally, VA offers a range of benefits to spouses, dependents, survivors, and caregivers of veterans. Family members may be eligible for health care through CHAMPVA, life insurance options, education benefits, and survivors’ compensation, depending on their relationship to the veteran and their individual circumstances. Survivors may qualify for burial assistance and monetary benefits like Dependency and Indemnity Compensation (DIC), along with burial support services. Additionally, educational programs such as Survivors’ and Dependents’ Education Assistance (DEA, also known as Chapter?35) and the Fry Scholarship help with tuition, fees, and supplies.

Caregivers to veterans, such as spouses or other close family members, can access specialized Caregiver Support Programs. The Program of General Caregiver Support Services (PGCSS) offers broad assistance including training, peer mentoring, coaching, respite care, and access to VA and community resources. For caregivers of veterans with serious, service?connected conditions rated 70% or higher, the Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) provides more intensive support, including education, mental health counseling, respite care, travel benefits, health care via CHAMPVA if uninsured, and a monthly stipend.

Funding for Veterans’ Programs

VA’s programs consist of both discretionary spending, which is subject to appropriations by Congress, and mandatory spending. VA’s mandatory spending includes disability compensation for veterans, DIC, pensions, VR&E, education programs, life insurance, and housing programs, among others. These entitlements are included in Congressional appropriations bills, though the funding levels are determined by statutory formulas. VA’s discretionary appropriations fund medical care, medical research, construction programs, IT, and other general operating expenses. VA has advanced appropriation authority for certain medical care and benefit accounts, which means that funds appropriated in one fiscal year are available to spend in future fiscal years.

The Department’s total budget in FY2024 was approximately $310 billion, of which $175 billion was mandatory spending and $135 billion was discretionary. The VBA received roughly $180 billion in funding and the VHA $120 billion, with $480 million for the NCA and $10 billion for departmental administration. For FY2025, Congress passed a full-year continuing resolution, generally holding discretionary spending flat across most of the Federal government. While total discretionary funding for VA fell to $129 billion, mandatory spending for VA increased by more than 35% to nearly $240 billion, for a total budget of $368 billion in FY2025. The increased mandatory funding in FY2025 was largely allocated to the VBA ($237 billion in total funding) and Congress also included $6 billion for the Cost of War Toxic Exposure Fund (TEF), which funds health care, claims processing, and other expenses related to providing care to veterans exposed to toxic substances.

Figure 1: Breakdown of FY2025 Enacted Funding for VA

Sources: Department of Veterans Affairs FY2025 Appropriations, Congressional Research Service, July 24, 2025; The Conference Board, 2025.

The nonpartisan CBO also makes 10-year projections for certain mandatory spending categories affecting veterans: income security (veterans’ compensation, pensions, and life insurance programs), TEF, Federal military retirement, and “other” (primarily GI Bill and similar education benefits). Between 2024 and 2035, CBO estimates spending on veterans’ income security programs will grow from $175 billion to $306 billion, TEF expenditures will grow from $19 billion to $67 billion, and education and other spending will increase from $12 billion to $25 billion. Including offsetting receipts, military retirement spending is projected to increase from $53 billion in 2024 to $79 billion in 2035.

Figure 2: CBO Projections of Certain Mandatory Spending Affecting Veterans (2024-2035)

Sources: The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035, Congressional Budget Office, January 2025; The Conference Board, 2025.

Impact of Veterans’ Programs

Based on 2023 data, VA estimates there are approximately 17.6 million living veterans in the US (VA uses a deterministic population projection model blending various VA and American Community Survey data sources because VA’s administrative data for older veterans is limited). In 2023, more than 40% of living veterans served in the Gulf War era (since 1990), 30% served during the Vietnam War, and 5% served in the Korean War and WWII. Roughly 80% of living veterans served during wartime. In FY2024, VA provided 127.5 million health care appointments, delivered $187 billion in benefits to 6.7 million veterans and survivors, and processed more than 2.5 million disability benefit claims. Among veterans, trust in VA reached 80% in 2024, up from 55% in 2016 (the first time VA conducted the survey). Veteran trust in VA health care was also more than 90% last year. Among Americans overall, 56% of respondents in a 2023 survey had a favorable opinion of VA, with similar shares of Republicans and Democrats holding favorable views. Nearly 80% of Americans also have broad confidence in the military to act in the public’s best interests, demonstrating the overall favorable opinion that the US population has of the Nation’s military and its veterans.

Opportunities for Reform to Address Long-Term Fiscal Challenges

The Federal government’s rising spending on VA’s budget and other programs for veterans comes in the context of the unsustainable US national debt, which recently reached a record $36.7 trillion. Government spending also exceeded government revenues by $1.9 trillion in FY2024. To finance this increasing spending, the Federal government will continue issuing debt in the form of Treasury securities, which will in turn increase the costs of servicing the national debt and begin crowding out other spending priorities, which could include the discretionary portion of spending on veterans. As such, Congress can consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations, which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate. Congress should also protect vulnerable populations of veterans, their families, and other stakeholders by gradually phasing in any legislative changes to provide beneficiaries sufficient time to adjust.

CBO, the nonpartisan agency that produces independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional budget process, has described several options that would produce large reductions to the deficit (each option would require a statutory change). Policymakers should consider the tradeoffs from these policies to balance the decreases in spending with the reductions in coverage and benefits under the affected veterans’ programs.

The first set of options concerns VA disability compensation. One option would be to means test eligibility for VA disability compensation, restricting benefits for veterans with total household income above $135,000 (corresponds to the 70th percentile of total household income in the US) by decreasing disability compensation by one dollar for every two dollars of gross household income above the threshold, generating a deficit reduction of $384 billion over 10 years. Another option would limit Individual Unemployability (IU) payments for veterans age 67 or older, which is the full retirement age for Social Security benefits for those born after 1959. These IU payments are supplemental compensation for veterans who have a disability rating of between 60 and 90 percent and VA determines cannot maintain substantial gainful employment due to the service-connected disability. Eliminating IU payments for all veterans 67 or older would reduce the deficit by over $60 billion over 10 years, while ending these payments for prospective applicants starting in December 2025 would reduce the deficit by $13.5 billion over 10 years. A third option would reduce disability compensation payments by 30 percent at age 67 for all veterans who start receiving disability compensation in 2026 or later, which CBO projects reduces the deficit by almost $34 billion over 10 years (veterans who already collect disability compensation would see no change). A fourth option would require disability ratings of 30 percent or higher for VA disability compensation (CBO estimates about 20 percent of veterans have a disability rating below 30 percent). Narrowing eligibility for all veterans would reduce the deficit by almost $60 billion over 10 years, while restricting eligibility for new applicants would reduce the deficit by approximately $11 billion over the next decade. Finally, Congress could include VA’s disability benefit payments in taxable income, decreasing the deficit by nearly $235 billion over 10 years due to higher tax revenue; this option is controversial as disability benefits are compensation for injury and a veteran’s sacrifice, not earned income that the Federal government typically taxes.

The next set of options concerns health care for veterans and the active-duty military (as changes for TRICARE would also affect active-duty servicemembers). One option would end enrollment in VA’s health care system for all veterans in priority groups 7 and 8 (about 1 million veterans in 2023), reducing the deficit by approximately $60 billion over 10 years. Some of these veterans would be eligible for Medicare, increasing mandatory spending on that program and thus lowering the net deficit reduction to about $30 billion over the next decade. Two additional options concern TRICARE. Beneficiaries eligible for TRICARE are automatically enrolled in TRICARE for Life (TFL) when they become eligible for Medicare, with TFL paying nearly all medical costs not covered by Medicare for no enrollment fee. About 2.5 million people are currently enrolled in TFL. Charging an enrollment fee for TFL (set to match the fees for the preferred-provider plan in TRICARE paid by retirees who were not yet eligible for Medicare and who entered service after 2017, or about $610 for individual coverage and $1,220 for family coverage in 2027) would produce an estimated net reduction in the deficit of $17 billion over 10 years. Introducing minimum out-of-pocket requirements for TFL, specifically by implementing a deductible of $850 and cost sharing of 50 percent of the next $7,650 (thresholds comparable to certain high deductible private Medigap plans), would reduce the deficit by more than $30 billion over 10 years. The thresholds for both options would grow by the same rate as average Medicare costs in later years.

An alternative delivery system for veterans’ health care benefits is enrolling veterans in Medicare instead of the VHA. A 2016 analysis found that providing a full Medicare Part A, Part B, and Part D benefit as well as Part D deductibles and a typical Medigap policy would cost less than VHA medical care funding. The prospective savings from this alternative delivery of health care would have to be balanced with the administrative burden of selling VHA assets and the unemployment and economic effects of downsizing the significant VHA workforce. Other potential health care reforms include increasing access to VA community care, particularly to address mental health conditions and addiction and promote continuity of care. While VA community care has the potential to reduce barriers to access and long wait times for appointments, the cost and quality of community care compared to VHA-delivered care is still largely unknown, meriting further research. Finally, VA is deploying the Federal Electronic Health Record system in VA medical centers and associated clinics across the country, allowing clinicians to access a veteran’s full medical history in one location easily.

Regarding the programs VBA manages, VA has undertaken several initiatives to modernize benefits delivery and promote digital transformation. VA has established an online platform to access and manage VA education benefits, launched a disability compensation claim tool to facilitate the submission of claims, and implemented an online debt management tool as a central location to access and manage a veteran’s debt information. VA is also focusing on improving the DIC claims process for survivors and dependents of deceased veterans. In 2025, Congress passed and the President signed the VA Home Loan Program and Reform Act, which authorizes VA to take certain actions in cases of default on home loans under the VA home loan program and establishes a partial claim program on VA loans for primary residences that are in default or at imminent risk of default. These new operational and legislative efforts must be considered in light of the reduction of staff within the VA, estimated to be nearly 30,000 employees by the end of FY2025.

Conclusion