Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

Medicaid, a joint Federal-State program, provides health insurance coverage for more than 20 percent of Americans and is particularly important for certain populations, including low-income families, children, pregnant women, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities. Medicaid is jointly operated by states and the Federal government and comprises a large share of both state budgets and overall Federal health care expenditures. As program costs grow despite projected declines in enrollment over the next decade, Congress should consider opportunities for reform to put Medicaid on a sustainable financial trajectory and preserve vital benefits for tens of millions of Americans.

This Explainer provides a description of Medicaid expenditures and program financing; a brief history of the program; the role of states in Medicaid; Medicaid eligibility, benefits, and other program components; Medicaid’s impact; and opportunities for reform outlined by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to set Medicaid on sounder financial footing.

- Federal spending on Medicaid is estimated to be $656 billion in 2025. CBO estimated in January 2025 that spending is expected to rise to $1 trillion by 2035, even with a projected decrease in the number of Medicaid beneficiaries, because of spending on long-term care and an increase in health care costs.

- Two separate factors, rising health care costs in the US and policy changes that have increased coverage and access to Medicaid services, have driven this increase in Medicaid expenditures, which contributes to annual deficits and puts pressure on the Federal budget.

- Medicaid was established in 1965, and eligibility was initially tied to receipt of Federal cash assistance for children, low-income families, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities. Reforms in the 1990s severed the link with cash welfare payments and legislation in the 2010s expanded coverage to more low-income adults.

- States have flexibility in designing their Medicaid programs within broad Federal guidelines, leading to wide variation in eligibility, services covered, and the delivery system used for Medicaid benefits.

- In general, Medicaid covers children, pregnant women, adults earning income below a certain level, individuals with disabilities, and individuals 65 years of age and older. Medicaid also has financial eligibility criteria that beneficiaries must meet, and Medicaid eligibility is typically redetermined on an annual basis.

- Medicaid offers comprehensive health care coverage and is the largest payor for long-term services and supports (frequently for the elderly), births, and behavioral health services in the US. State Medicaid programs have increasingly used managed care to deliver these health care benefits, and states have flexibility to develop benefit packages for targeted populations, including those with complex or chronic health care needs.

- Given Medicaid’s financial trajectory, policymakers should consider opportunities for reform, including caps on Federal Medicaid spending, limits on the use of state taxes on health care providers, and adjustments to Federal Medicaid matching rates. Innovative strategies such as value-based care and an emphasis on primary care, preventive care, and coordination of benefits can also assist in improving Medicaid’s fiscal outlook.

Introduction

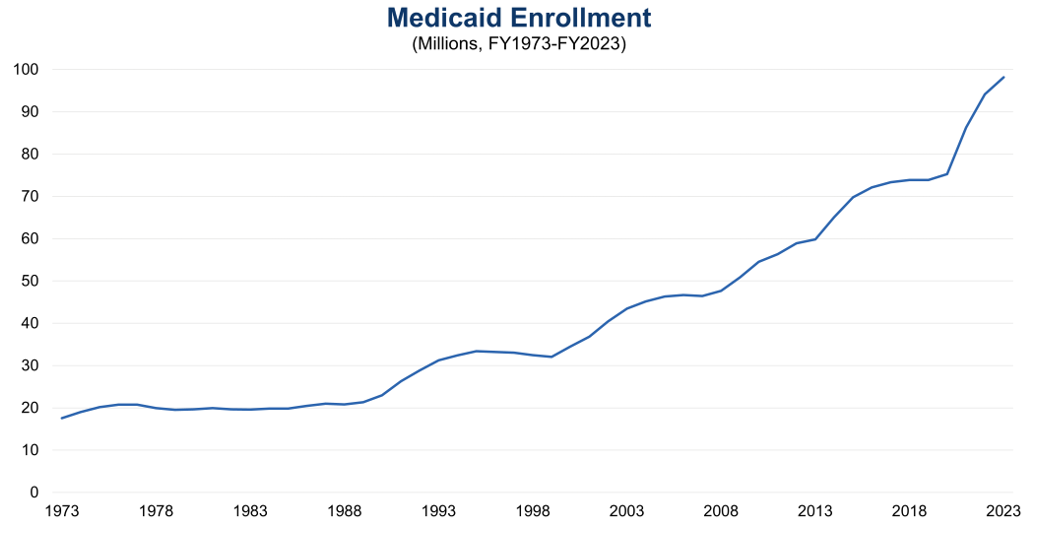

Medicaid is a joint Federal-State health insurance plan for lower-income Americans and those with limited resources, providing coverage primarily to low-income adults, pregnant women, and children. Medicaid covered 100 million individuals (as of fiscal year 2023, the last year for which data are available) and it is the largest payor of mental health services, long-term care services, and births in the US. Federal law requires states to cover specific eligibility groups and services, and states have the flexibility to include additional groups and covered services under their Medicaid program as well as seek waivers for additional modifications to tailor programs to certain sub-populations or areas within the state.

Medicaid Expenditures and Financing

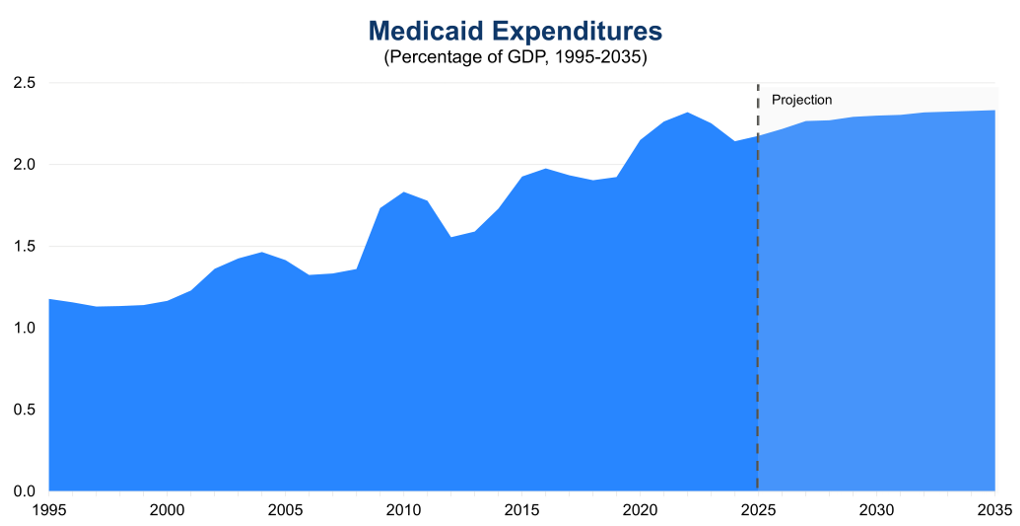

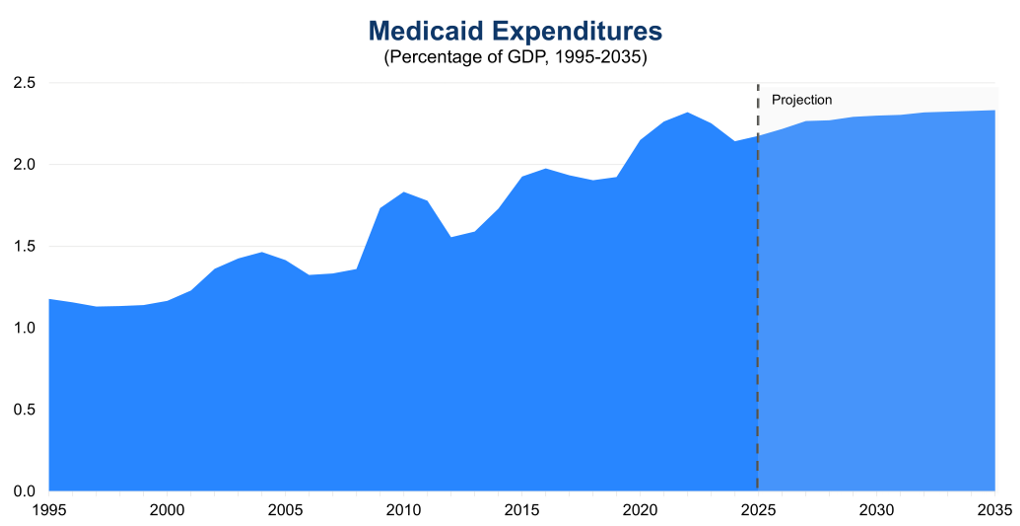

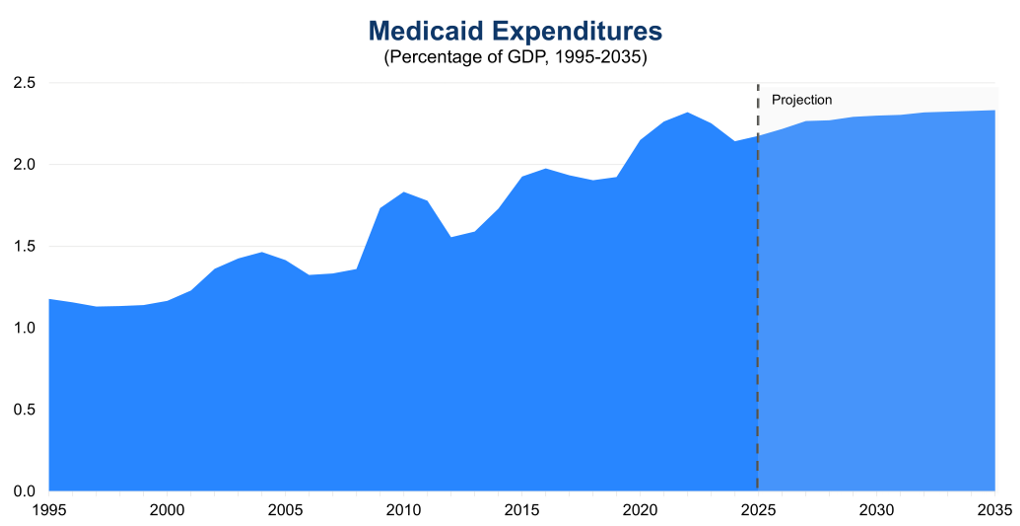

CBO projected in January 2025 that Federal Medicaid spending will reach $656 billion in fiscal year (FY) 2025, with spending projected at that time to rise to $1 trillion by 2035. This spending increase is projected to occur even as CBO estimated in 2024 that total Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollment would decline from 92 million in 2024 to 79 million people by 2034, in part because of Medicaid redeterminations following the pandemic and in part because of some states’ more restrictive enrollment policies. Medicaid spending has increased for a variety of reasons, including rising US health care costs, coverage expansions, an increase in the number of elderly and disabled individuals requiring more long-term care, increases in provider payment rates over the rate of inflation, and enhanced Federal cost matching under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA).

Figure 1: Total Federal Medicaid Expenditures (1994-2035)

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections (January 2025), Historical Budget Data (January 2025), and Economic Projections (January 2025); The Conference Board, 2025.

Rising health care costs are a feature of the US health care system, and Medicaid is no exception. The US already has the highest health care costs per capita compared to other advanced countries. Higher costs are tied to higher prices for most health care services and prescription drugs compared to other advanced economies—utilization of services is less of a factor because certain services, including physician consultations per capita and the average length of hospitals stays, are lower in the US compared to other advanced economies. Rising health care costs per beneficiary put pressure on the Federal budget, which is already running sustained, record-breaking deficits. To finance this spending, the Federal government will continue issuing debt in the form of Treasury securities, which will in turn increase the costs of servicing the national debt and begin crowding out other spending priorities.

A key feature of the Medicaid program is joint Federal and state financing. The Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) determines the Federal share for most health care services. Per capita incomes in each state form the basis of the FMAP formula, with higher reimbursement going to states with relatively lower per capita incomes. For example, Mississippi’s FMAP is approximately 77 percent in FY2026, and New York and nine other states have an FMAP of 50 percent. Federal law sets a minimum FMAP of 50 percent and a maximum of 83 percent. Exceptions exist for specific populations, services, and providers, with the Affordable Care Act optional expansion population (discussed below) having an FMAP of 90 percent and certain administrative expenses having an FMAP of 75 percent or higher. Importantly, there is no cap on overall Federal Medicaid spending, which varies by enrollment, utilization, and the types of benefits and eligibility groups states decide to cover.

States finance their share of Medicaid expenditures in five ways, sometimes with the financial assistance of local governments and health care entities. States can use their general funds, which hold revenue collected through income and sales taxes and other sources. States can impose health care-related taxes (also known as provider taxes, fees, or assessments) as long as at least 85 percent of the tax burden falls on health care providers or services or if the tax treats health care providers differently than other entities. Health care providers can make voluntary contributions, known as provider donations, to cover the non-Federal share of certain Medicaid expenditures. Public agencies and local governments, including state university hospitals and state psychiatric hospitals, can make intergovernmental transfers to the state. Finally, states and local governments can certify that certain expenditures are eligible for Federal matching funds, known as certified public expenditures.

In FY2018, state funds made up 68 percent of the non-Federal share of Medicaid payments, with provider taxes and donations providing 17 percent and local governments providing 12 percent. Overall, Medicaid expenditures form a significant part of state budgets—roughly 29 percent of state budgets (as of state FY 2022, the last year for which data are available) goes towards Medicaid when all Federal and state funds are included.

Brief History of Medicaid

Congress enacted Medicaid alongside Medicare in 1965, primarily to provide coverage to groups that were historically excluded from obtaining private insurance, such as individuals with disabilities who require long-term services and supports or low-income residents in regions with limited providers or insurance coverage. This legacy means that Medicaid offers benefits that are not typically covered by many private insurers, such as home and community-based services. Medicaid eligibility was initially linked to receipt of aid under the former Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), in existence until 1997, which provided cash welfare payments for needy children receiving limited or no support from their parents. When Congress established the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program in 1972 to federalize cash assistance for the aged, blind, and disabled, these beneficiaries also became entitled to Medicaid coverage. (For those enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid, Medicare is the primary payor and Medicaid the payor of last resort.)

In the 1980s, Congress established Medicaid waivers to allow states to pursue mandatory managed care enrollment of certain Medicaid populations and to cover home and community-based long-term care services upon approval by the former Health Care Financing Administration, now the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Congress also expanded eligibility to all AFDC-eligible pregnant women.

In the mid-1990s, Congress made fundamental changes to the operations of the Medicaid program. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 repealed AFDC and replaced it with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. This law also severed the link between AFDC and Medicaid, so that enrollment in or termination of Medicaid was no longer automatic with the receipt or loss of AFDC cash assistance. In 1997, in the Balanced Budget Act, Congress established Federal matching funds to expand health insurance coverage for children in families with incomes above states’ Medicaid eligibility levels and updated payment policies for managed care and other health care providers.

In the 2010s, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA) expanded Medicaid eligibility to include nearly all individuals under age 65 with incomes up to 133 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius in 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress could not force states to participate in this expansion of Medicaid coverage. Since enactment of PPACA, 41 states (including DC) have expanded Medicaid eligibility at least to some extent under its provisions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress passed temporary FMAP increases to support state budgets and local economies on the condition that states did not disenroll Medicaid beneficiaries. This provision ended March 31, 2023, leading to a process termed Medicaid unwinding, which removed 25 million recipients from state Medicaid rolls as of September 2024, even as enrollment remained higher than before the pandemic. States also took advantage of emergency authorities during the public health crisis to expand use of telehealth and Medicaid eligibility and benefits, as well as address workforce issues for home and community-based services.

More recently, Public Law 119-21 (H.R. 1, 2025), also referred to as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” or OBBBA, made significant changes to the Medicaid program. The Act restricts the ability for states to raise Medicaid provider taxes (discussed more below), requires states to establish Medicaid community engagement requirements (i.e., 80 hours of work, community service, work program, and/or educational program participation per month) for able-bodied adults without dependents, delays implementation until 2035 of the Eligibility and Enrollment final rule that streamlined application and enrollment processes for Medicare Savings Programs and Medicaid, reduces Medicaid state directed payments from the average commercial rate to 100% of the Medicare rate (for PPACA optional expansion states) or 110% of the Medicare rate (for non-expansion states), and enhances eligibility checks while limiting eligibility for lawfully present immigrants. The Act also includes a Rural Health Transformation Program appropriating $10 billion annually for five years ($50 billion total) for states to apply for funding for rural hospitals and other specified rural health facilities (e.g., federally qualified health centers, community mental health centers, and rural health clinics); many of these facilities have a high percentage of Medicaid recipients. Following the enactment of the OBBBA, CBO estimated the Medicaid policy changes in the Act will reduce the deficit by nearly $940 billion between 2025 and 2034 and will increase the number of people without health insurance by 7.5 million by 2034.

Overview of the Medicaid Program

CMS in the Department of Health and Human Services is responsible for overseeing the Medicaid program at the Federal level. Each state administers its own Medicaid program following broad national guidelines established by Federal statutes, regulations, and policies. Medicaid’s actual delivery of benefits relies on a health care system comprising private health plans under contract to state governments, hospitals, physicians, and other medical providers.

Role of States

While participation in Medicaid is voluntary, all states, the District of Columbia, and all US territories have chosen to participate. Medicaid is also an entitlement for states, which means that states are entitled to Federal Medicaid matching funds if they operate their Medicaid programs within Federal requirements. Thus, total spending on a state’s Medicaid program depends both on that state’s policy decisions, including its decisions on eligibility and coverage, contracts with health plans managing Medicaid services, and the utilization of Medicaid benefits by enrollees within that state.

States typically describe how they will operate their Medicaid programs through a state plan approved by CMS. States have discretion regarding how they determine certain eligibility criteria for Medicaid enrollees and may request a waiver of Federal law from CMS to extend health coverage to groups not described in Federal law or to modify how the state’s Medicaid program provides care. States may also target specific benefits to certain groups through various state plan options, use waiver authority to customize benefits to specified Medicaid subgroups, and offer services outside the standard benefit packages. As such, there exists considerable variation across state Medicaid programs.

Eligibility

Medicaid eligibility is determined by several factors: categorical criteria, financial criteria, whether including a group in a state plan is mandatory or optional under Federal law, and the extent of a state’s discretion in determining the eligibility criteria for a group. In general, assuming eligibility criteria are met, Medicaid can cover children, pregnant women, adults earning income below a certain level, individuals with disabilities, and individuals 65 years of age and older.

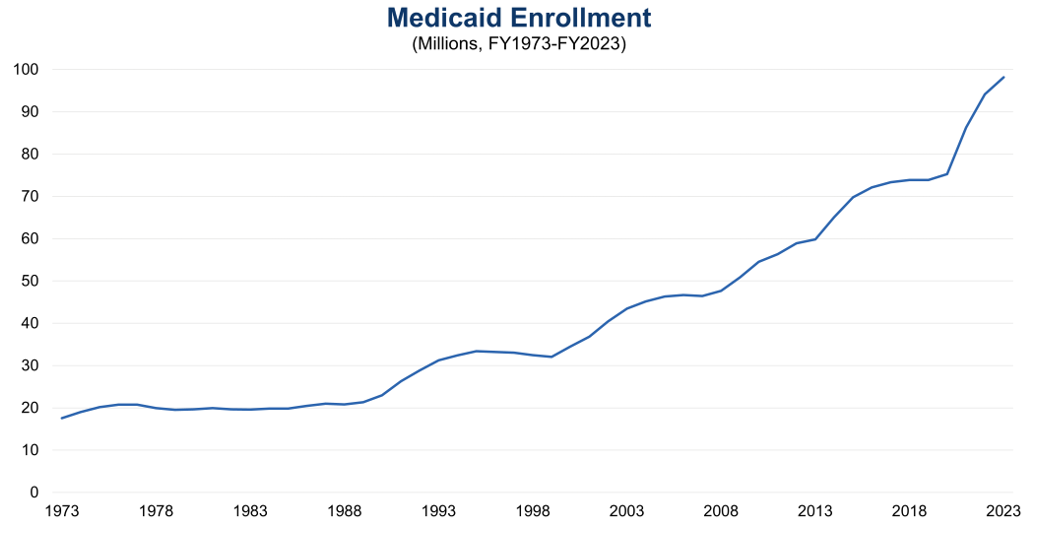

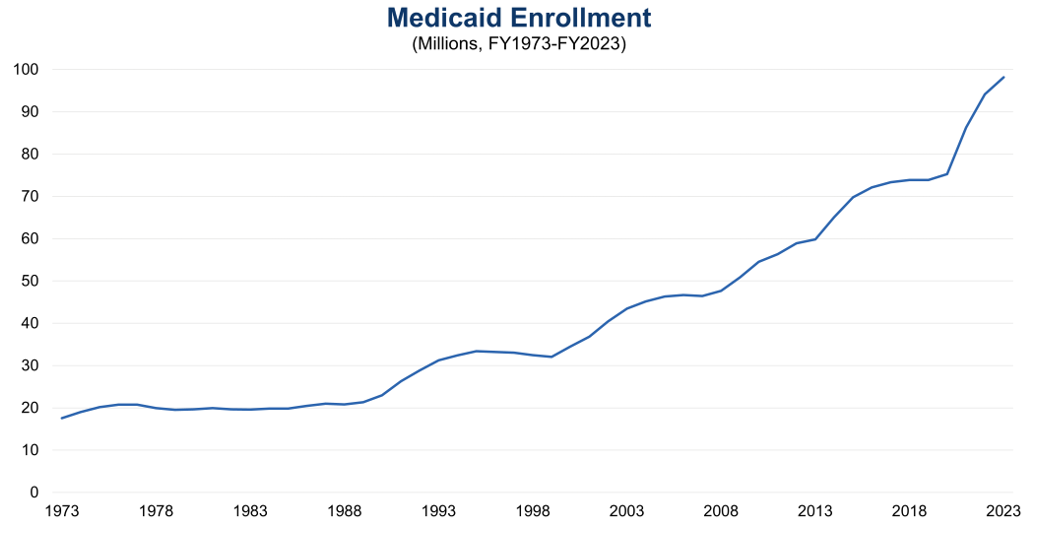

Figure 2: Total Medicaid Enrollment (FY1973-FY2023)

Sources: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), Exhibit 10, Medicaid Enrollment and Total Spending Levels and Annual Growth, December 2024; The Conference Board, 2024. (Last fiscal year for which data are available)

Federal law requires states to cover certain eligibility groups, known as mandatory categorically needy, which include low-income families, qualified pregnant women and children with annual family income at or below 133 percent of the FPL, children receiving foster care or adoption assistance under Title IV-E of the Social Security Act, and individuals obtaining Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits. States also have the option to cover other groups, known as optional categorically needy, including pregnant women and infants with annual family income between 133 and 185 percent of the FPL, individuals obtaining home and community-based services, and children in foster care who are not otherwise eligible.

Additionally, states can establish a medically needy program for individuals with significant health needs whose income is too high to otherwise qualify for Medicaid. These individuals must “spend down” their income above a state’s medically needy income standard by incurring expenses for medical care, at which point Medicaid pays the cost of medical and other health-related services that exceeds the expenses the individual had to incur to become eligible for Medicaid. One common use of this program is as a safety net for older adults that provides a pathway to qualify for Medicaid to help pay for long-term care.

Two Medicaid eligibility groups are worth highlighting. The PPACA allows states to expand Medicaid eligibility to all nonelderly adults with income at or below 133 percent of the FPL. As an incentive for states to expand coverage to this optional population, the Federal government provides an enhanced FMAP of 90 percent for these individuals. As of August 2025, 41 states (including DC) have adopted this Medicaid expansion.

Some individuals are also eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare, referred to as dual eligibles. This group of individuals is a growing population within Medicaid, with 13.7 million dually eligible individuals enrolled in Medicaid in FY2022, up from 8.6 million in 2006. Dual eligibles may have partial or full Medicaid benefits and Medicaid assists with some or all of an individual’s Medicare premiums and cost sharing. Dual eligibles represent a disproportionate share of Medicaid expenditures because of higher rates of chronic illnesses, significant long-term care needs, and mental health diagnoses, accounting for 32 percent ($244.5 billion) of Medicaid expenditures in FY2022 despite only making up 15 percent of Medicaid enrollees.

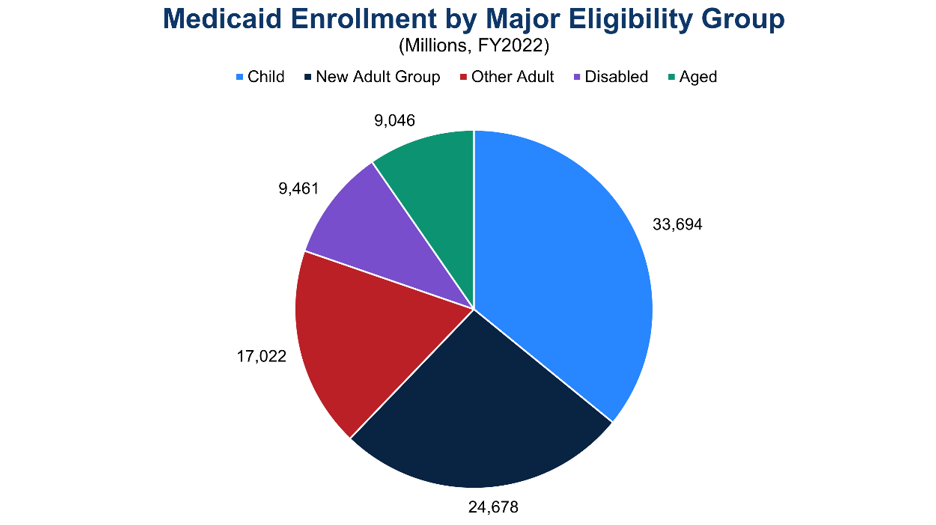

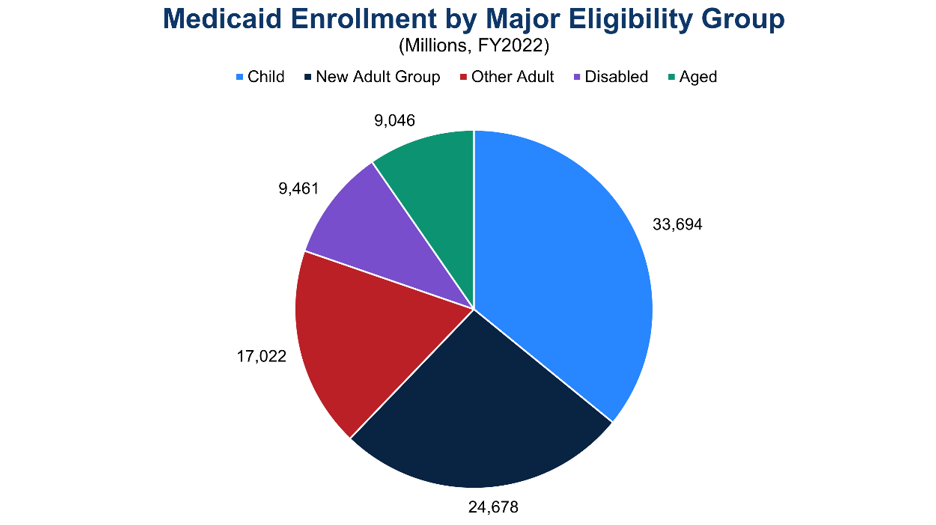

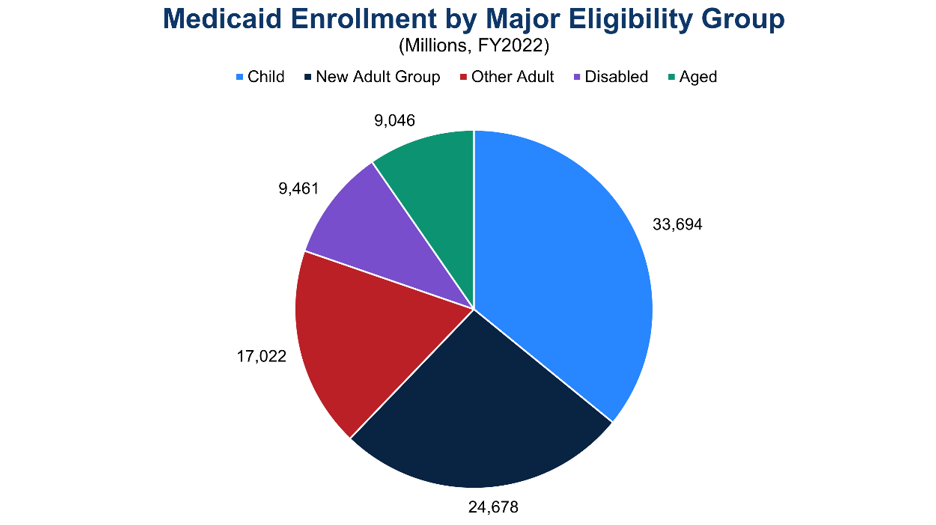

Figure 3: Medicaid Enrollment by Major Eligibility Group (FY2022)

Notes: “New Adult Group” refers to PPACA optional expansion population; “Disabled” refers to children and adults under age 65 who qualify for Medicaid on the basis of disability; “Aged” refers to individuals age 65 and older who qualify for Medicaid through an aged, blind, or disabled pathway. (Last fiscal year for which data are available)

Sources: MACPAC, Exhibit 14, Medicaid Enrollment by State, Eligibility Group, and Dually Eligible Status, October 2024; The Conference Board, 2024.

To determine financial eligibility, Medicaid generally uses a methodology based on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI), which considers taxable income and tax filing relationships. The MAGI methodology does not allow income disregards, nor does it allow an asset or resource test. Most children, pregnant women, parents, and nonelderly adults use MAGI to determine their financial eligibility. Individuals whose eligibility is based on blindness, disability, or age (65 or older) use the income methodologies of the SSI program to determine their financial eligibility. Other groups, such as individuals obtaining SSI and children obtaining adoption assistance under Title IV-E of the Social Security Act, do not require a determination of income to enroll in Medicaid.

Once a state Medicaid agency determines an individual eligible for Medicaid, coverage is effective on the date of application or the first day of the month of application. Benefits may be covered retroactively for up to three months prior to the month of application, and coverage stops at the end of the month when a person no longer meets eligibility requirements. Medicaid eligibility is generally subject to annual redetermination. Medicaid beneficiaries must also generally be residents of the state in which they receive Medicaid and must be either US citizens or lawful permanent residents. The OBBBA will require eligibility redeterminations to be conducted every six months starting in 2027.

Medicaid Benefits

Medicaid requires that states provide a collection of mandatory benefits under Federal law. These mandatory benefits include services for inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, physician, nursing facility, family planning, laboratory and X-ray, and Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT). States may also cover optional benefits, such as dental services, physical and occupational therapy, prescription drugs, eyeglasses, and primary care case management.

To deliver these benefits, states offer two primary benefit packages. Traditional Medicaid benefits are packages of mandatory and optional services that are subject to four broad Federal guidelines related to sufficiency of amount, duration, and scope; comparability; statewideness; and freedom of choice. These

guidelines exist to ensure a service reasonably achieves its purpose, is equal across various population groups, is the same statewide, and provides choice among health care providers. States have discretion in the breadth of coverage for a given benefit within these four Federal guidelines.

States also offer alternative benefit plans (ABPs), which provide comprehensive benefit coverage based on a coverage benchmark as opposed to a list of discrete services under traditional Medicaid. ABPs must include the essential health benefits that most private insurance plans cover, EPSDT benefits, family planning services, and transportation to and from health care providers. States may waive the statewideness and comparability requirements under traditional Medicaid to define populations that will be served by an ABP. The Federal government requires that individuals in the PPACA optional expansion population receive ABP coverage.

In general, premiums and cost sharing under Medicaid are limited. States may charge limited premiums to certain groups of Medicaid enrollees, such as pregnant women with family income above 150 percent of the FPL or qualified disabled and working individuals with income above 150 percent of the FPL. States may also charge copayments for prescription drugs and non-emergency use of the emergency department. However, certain groups, such as pregnant women, and services, including preventive services for children, are exempt from cost sharing in Medicaid under the Social Security Act.

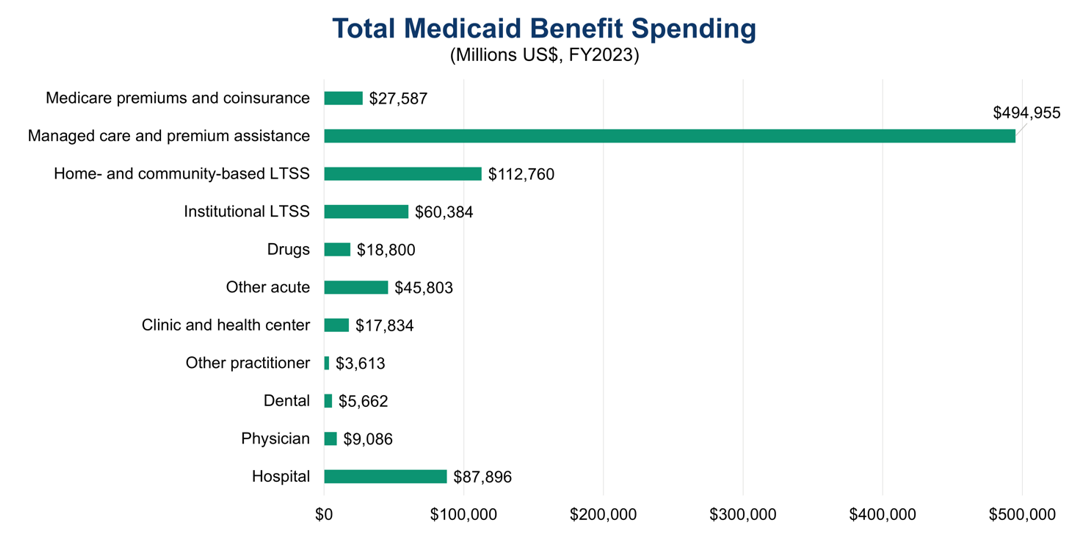

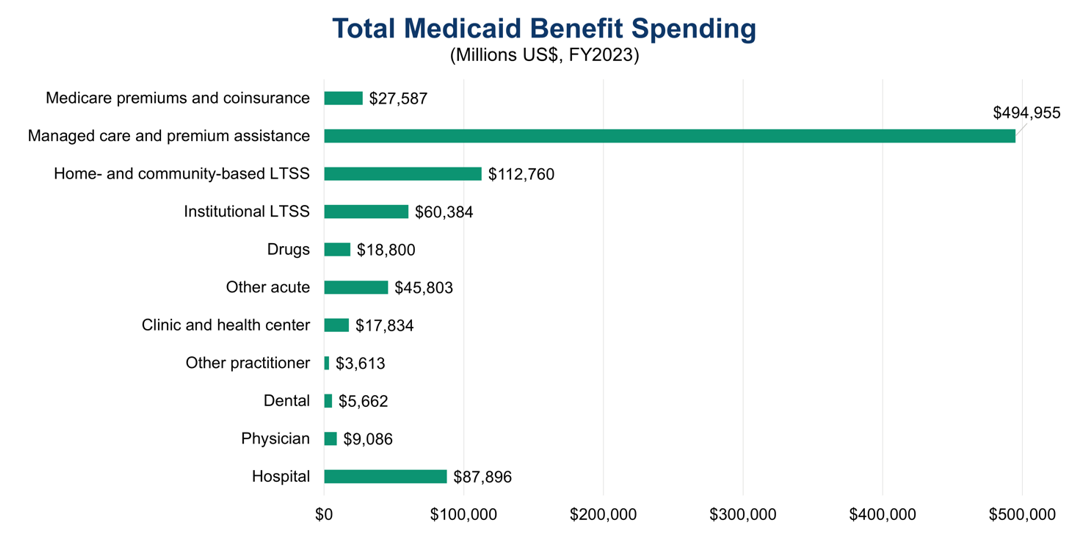

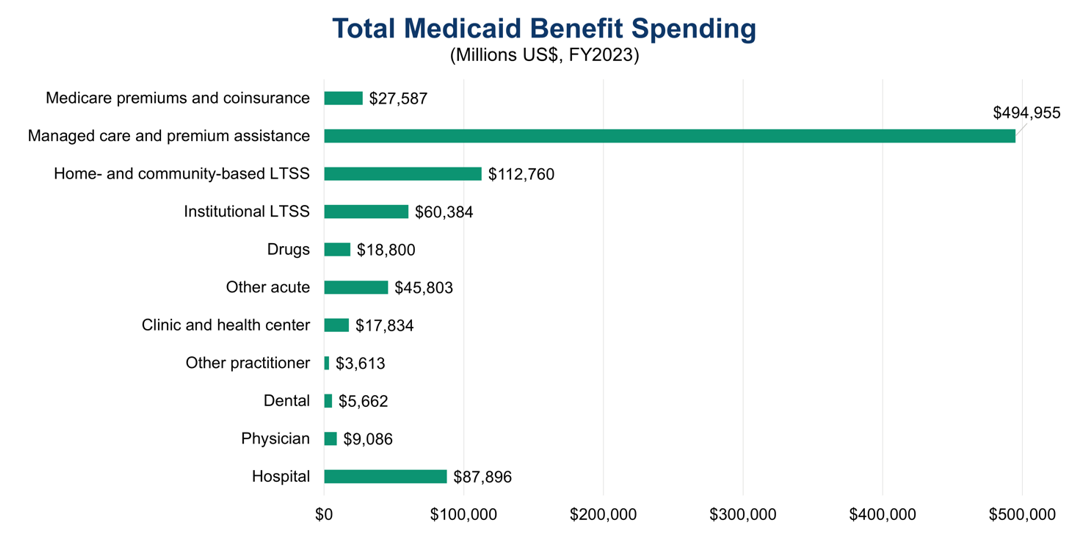

Figure 4: Medicaid Spending on Benefits by Major Category (FY2023)

Notes: Excludes collections from Medicaid enrollees; all categories are fee-for-service benefits apart from “Managed care and premium assistance” and “Medicare premiums and coinsurance.” (Last fiscal year for which data are available)

Sources: MACPAC, Exhibit 17, Total Medicaid Benefit Spending by State and Category, September 2024; The Conference Board, 2024.

Medicaid Managed Care

Historically, the Medicaid delivery system has operated on a fee-for-service basis, meaning that state Medicaid programs paid health care providers for each service they delivered to Medicaid enrollees. Since the 1990s, Medicaid has moved towards managed care, in which state Medicaid programs contract with one or more organizations to provide benefits to Medicaid enrollees. These managed care organizations (MCOs), which are private health insurance companies, typically receive payments on a capitated basis. Under capitated payment arrangements, MCOs receive a fixed per member per month prospective payment for each Medicaid enrollee that they cover. MCOs are then responsible for arranging health care services for their Medicaid enrollees and paying health care providers.

As of July 2022, nearly 75 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in comprehensive risk-based managed care, in which enrollees receive a comprehensive package of health benefits from an MCO. Approximately 6 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in primary care case management (PCCM), contracts between state Medicaid programs and primary care providers to provide case management services to Medicaid enrollees. Primary care providers receive a monthly case management fee for each enrollee, though they continue to bill the Medicaid program on a fee-for-service basis for medical care. Medicaid also has limited benefit plans that provide coverage for one or two Medicaid services on a capitated basis, such as behavioral health benefits, dental services, and transportation. Some states, including Hawaii and South Carolina, exclusively provide Medicaid benefits via managed care, while others, including Alaska and Connecticut, do not provide managed care coverage.

Waivers and Long-Term Care

In addition to the flexibilities described above, states have several waiver and demonstration authorities that allow them to experiment with different approaches to deliver health care or tailor programs to the needs of particular populations or geographic areas. States apply to CMS for these waivers, which are time-limited and may be subject to reporting, evaluation, and financing requirements. Each waiver is tied to a specific section of the Social Security Act and allows state Medicaid programs to waive one or more of the four Federal guidelines that govern traditional Medicaid benefits.

A prominent waiver authority is the Section 1915(c) home and community-based services (HCBS) waiver. This waiver allows states to develop programs for individuals who prefer to obtain long-term care services and supports in their home or community as opposed to in an institutional setting. States must demonstrate that the waiver services will not cost more than providing these services in an institution, ensure the protection of a beneficiary’s health and welfare, provide adequate and reasonable provider standards to meet the needs of the target population, and ensure that services follow an individualized and person-centered plan of care. In exchange, states receive a waiver of the statewideness and comparability Federal guidelines and of certain income and resource rules to target services to areas with the greatest need or to certain groups who are at risk of institutionalization, such as the elderly and people with intellectual disabilities. Almost all states operate at least one 1915(c) HCBS waiver.

Another popular waiver authority is the Section 1915(b) managed care and freedom of choice waiver. States can use Section 1915(b) waivers to implement their managed care programs by requiring enrollment in managed care, utilizing a centralized broker for managed care enrollment, using cost savings to provide additional services to enrollees, and/or limiting provider networks. CMS approves Section 1915(b) waivers for two years at a time.

States may also conduct Section 1115 demonstrations to develop experimental or pilot programs with the goal of demonstrating and evaluating state-specific policy approaches to better serve Medicaid beneficiaries. CMS reviews Section 1115 demonstrations on a case-by-case basis, and the applications must show how the demonstrations will be budget neutral to the Federal government. CMS approves these programs for an initial five-year period, which can be extended by an additional three to five years. States have used this authority in a variety of ways, including to expand coverage to new populations, institute work or community engagement requirements, address an enrollee’s housing or other health-related social needs, and offer different combinations of services in different areas of the state. Starting in 2027, the OBBBA prohibits CMS from approving an application for or renewal of a Section 1115 demonstration unless the Chief Actuary for CMS certifies the demonstration is budget neutral to the Federal government.

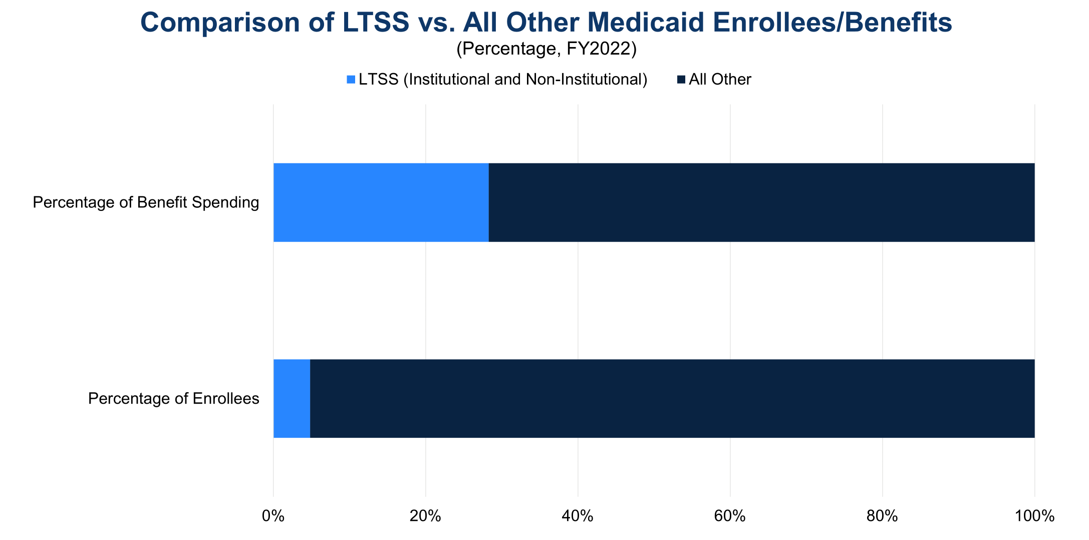

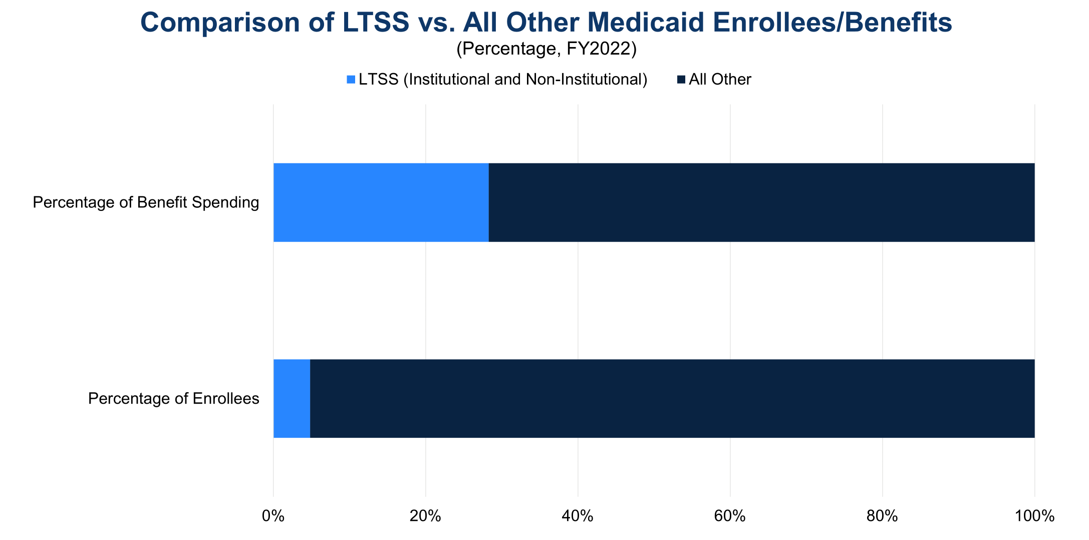

In general, Medicaid is an important provider of long-term care, also known as long-term services and supports (LTSS), with over 30 percent of total Medicaid spending going to LTSS in FY2020. Medicaid beneficiaries must typically demonstrate the need for LTSS by meeting functional, disease, or condition-specific eligibility criteria set by states. LTSS can be provided in an institutional setting such as a nursing home or in the home or community as is done through HCBS. There are separate financial eligibility rules to obtain Medicaid-covered LTSS regarding limits on the value of home equity and asset transfer rules. Eligibility for Medicaid LTSS generally requires a “spend down” of assets and income to reach asset and income limits for LTSS, which can involve a five-year look-back period of past transfers to prevent the gifting of assets or selling them under market value to qualify for LTSS.

States have three main state plan options to provide LTSS coverage to targeted populations of Medicaid beneficiaries. Section 1915(i) of the Social Security Act, first enacted in 2005, allows states to offer a wide range of HCBS for specific populations, and states can tailor the benefit package by population by adjusting the amount, duration, and scope of services. States can receive increased FMAP to offer community-based attendant services and supports to certain populations who require LTSS by using Section 1915(k) authority, also known as the community first choice state plan option. States can also integrate services and coordinate care for Medicaid enrollees with complex or chronic physical or behavioral health needs through Section 1945 authority, also known as health homes, and can receive enhanced FMAP during the startup phase of this program.

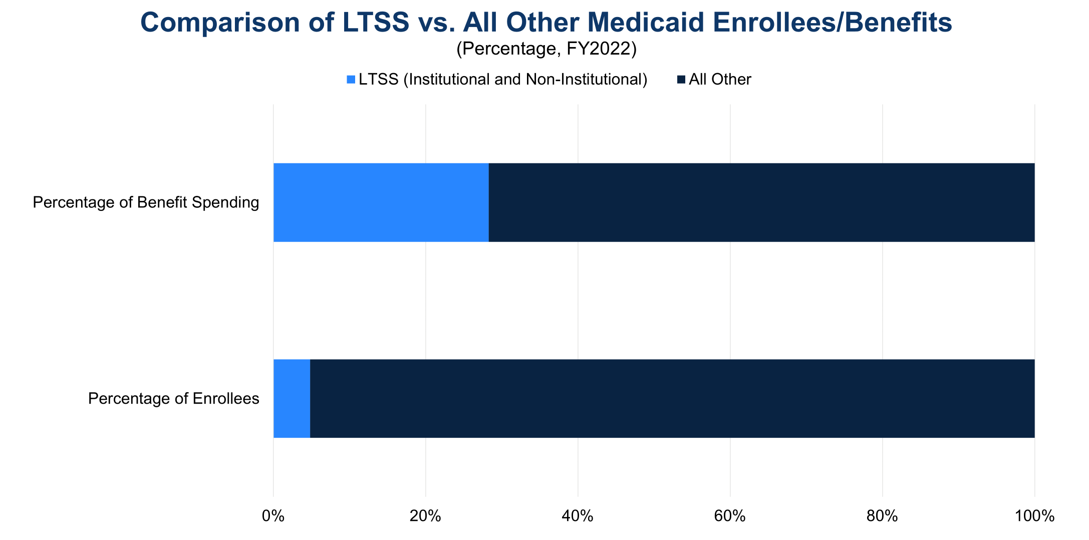

Figure 5: Comparison of LTSS Users and Benefit Spending vs. All Other Medicaid Enrollees and Services (FY2022)

Sources: MACPAC, Exhibit 20, Distribution of Medicaid Enrollment and Benefit Spending by Users and Non-Users of Long-Term Services and Supports, October 2024; The Conference Board, 2024. (Last fiscal year for which data are available)

Medicaid’s Impact

Medicaid has a significant impact on the US health care system, covering more than 20 percent of all Americans. Medicaid covers four in ten children, eight in ten children living in poverty, 41 percent of all births, and nearly half of children with special health care needs in the US, defined as children who “have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral or emotional conditions and also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.” Medicaid also covers almost half of adults living in poverty, five in eight nursing home residents, 23 percent of non-elderly adults with a mental illness, and 40 percent of non-elderly adults with HIV. Medicaid is the largest payor of LTSS and behavioral health services in the US and a key source of financing for certain providers such as federally qualified health centers, rural health clinics, and Indian Health Service facilities.

Medicaid’s impact is reflected in the program’s popularity across party lines. While Democrats and independents are more likely to view Medicaid favorably than Republicans, 29 percent of respondents in a 2023 poll held a very favorable view of the program and 47 percent held a somewhat favorable view of the program. The Medicaid PPACA optional expansion is also widely popular, so much so that seven states (Iowa, Maine, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Utah) have adopted the expansion via ballot measure, with voters effectively overriding state legislatures that refused to expand Medicaid eligibility. Two-thirds of respondents in non-expansion states including Texas and Florida want their state to expand Medicaid, demonstrating the value of Medicaid to many Americans.

Opportunities for Reform

Given the expected increase in Medicaid expenditures amid the Federal government’s sustained deficits, Congress should consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations to set Medicaid on a more sustainable fiscal path, which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate.

Congress should also protect vulnerable populations of Americans by gradually phasing in any legislative changes to provide Medicaid enrollees, health care providers, and health insurers sufficient time to adjust. CBO, the nonpartisan agency that produces independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional budget process, has described three options that would produce large reductions to the deficit. Policymakers should consider the tradeoffs from these policies to balance the decreases in spending with increased costs for states and health care providers and potential reductions in access to Medicaid services.

One policy option is caps on Federal Medicaid spending. These caps could be to overall spending, which would not be tied to changes in enrollment, or to per enrollee spending, which would make total Federal funding vary according to enrollment. In December 2024, CBO modeled these two types of caps alongside two potential growth rates based on the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Over ten years, overall spending caps would produce a net decrease in the deficit of $742 billion (with growth based on CPI-U) and a net decrease of $459 billion (with growth based on CPI-U plus one percentage point). Over a decade, caps on spending per enrollee would provide a net reduction in the deficit of $893 billion with growth based on CPI-U and a net reduction of $588 billion with growth based on CPI-U plus one percentage point. Policymakers have flexibility in selecting spending and eligibility categories, the base year, and the specific growth factor to balance this option’s tradeoffs.

Another policy option is to limit state taxes on health care providers. States in the late 1980s and early 1990s established taxes on health care providers that held providers harmless by returning funding to them in the form of higher Medicaid payments, with states pocketing additional revenue through Federal matching payments. To limit this practice, Congress prevented these “hold harmless” arrangements unless a state collects taxes at a rate that is less than six percent of a provider’s net revenues from treating patients. In December 2024, CBO modeled three changes to the threshold for this “safe harbor” exception over a ten-year period: 1) lowering it to five percent produces a net reduction in the cumulative deficit of $48 billion; 2) lowering it to 2.5 percent produces a net reduction of $241 billion; 3) and eliminating hold harmless arrangements would result in a net reduction of $612 billion. The OBBBA reduces the hold harmless threshold for provider classes other than nursing or intermediate care facilities by 0.5 percentage points annually starting in FY2028 until reaching 3.5 percent in FY2032, which CBO estimates will reduce the deficit by more than $190 billion over the next decade. Currently, 38 states have at least one provider tax over 5.5 percent of net patient revenues.

Finally, CBO analyzed in December 2024 the effects of reducing Federal matching rates on the deficit by modeling three scenarios. Reducing the Federal matching rate for certain administrative costs from 70-100 percent to the standard 50 percent would reduce the deficit by $69 billion over 10 years. Removing the FMAP floor of 50 percent would reduce the FMAP for the states with the highest per capita incomes to between 4 percent and 49.75 percent, resulting in a decrease in the deficit of $530 billion over 10 years. Aligning the current 90 percent FMAP for the PPACA optional expansion population with the FMAP for other Medicaid enrollees would produce a net decrease in the deficit of $561 billion over 10 years. In every scenario, states would have to backfill the loss of Federal funding with state funds or consider changes to Medicaid eligibility and benefits.

An innovative strategy to modernize Federal health programs is value-based care, which can be combined with alternative payment models to move away from a delivery system based on fee-for-service reimbursement. In practice, value-based care, which is increasingly used for Medicare and in commercial health insurance, means coordination and collaboration between physicians and other providers to focus on quality of care, provider performance, and the patient experience. To realize fully the potential of these innovative strategies, the Federal government, hospitals, and other medical providers should make the appropriate upfront investments in the health care workforce and data infrastructure. This will produce benefits throughout the US health care system, not just the Medicaid population.

In addition to value-based care, encouraging primary care, preventive care, and care coordination often leads to improved health outcomes throughout the health care system and potentially saves money for the health system in the long run by reducing the cost of care. This is true in particular for Medicare if these types of interventions are introduced earlier in a beneficiary’s life so that beneficiaries enter Medicare either healthier or already under treatment for chronic conditions. Similarly, interventions such as immunizations, promoting healthy lifestyle choices, and regular health screenings help reduce costs by preventing hospitalizations and identifying health conditions early. Private health insurers are increasingly employing care coordinators to assist their enrollees, and Medicaid has approved care coordination waiver programs in which dedicated staff assist patients with coordinating health care services. More broadly, the Administration and Congress should also assess strategies to streamline regulations and payment policies that are adding costs and administrative burden to the health care system.

Conclusion

Medicaid is a crucial health insurance program for low-income Americans, individuals with disabilities, and many seniors in long-term care. Together with Medicare, it accounts for the vast majority of Federal health spending. Given rising Federal health care costs and unsustainable Federal budget deficits, it is vital that Congress address Medicaid’s fiscal trends quickly to allow for adequate time to phase in changes to Medicaid. The longer the delays, the greater the chance that necessary legislative changes to preserve Medicaid will be disruptive to beneficiaries, health care providers, and the broader economy.

For Further Reading

- CED’s Solutions Brief, Modernizing Health Programs for Fiscal Sustainability and Quality, November 18, 2024

- CED’s Explainer, Medicare, August 2025

- CED’s Explainer, US National Debt, August 2025

- CED’s Policy Backgrounder, “Health Care Policy Update,” May 17, 2024

- “The Debt Crisis is Here,” Dana M. Peterson and Lori Esposito Murray, November 13, 2023

- CED’s Policy Backgrounder, “The End of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency,” April 14, 2023

- CED’s Solutions Brief, Debt Matters: A Road Map for Reducing the Outsized US Debt Burden, February 9, 2023

Trusted Insights for What’s Ahead®

Medicaid, a joint Federal-State program, provides health insurance coverage for more than 20 percent of Americans and is particularly important for certain populations, including low-income families, children, pregnant women, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities. Medicaid is jointly operated by states and the Federal government and comprises a large share of both state budgets and overall Federal health care expenditures. As program costs grow despite projected declines in enrollment over the next decade, Congress should consider opportunities for reform to put Medicaid on a sustainable financial trajectory and preserve vital benefits for tens of millions of Americans.

This Explainer provides a description of Medicaid expenditures and program financing; a brief history of the program; the role of states in Medicaid; Medicaid eligibility, benefits, and other program components; Medicaid’s impact; and opportunities for reform outlined by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to set Medicaid on sounder financial footing.

- Federal spending on Medicaid is estimated to be $656 billion in 2025. CBO estimated in January 2025 that spending is expected to rise to $1 trillion by 2035, even with a projected decrease in the number of Medicaid beneficiaries, because of spending on long-term care and an increase in health care costs.

- Two separate factors, rising health care costs in the US and policy changes that have increased coverage and access to Medicaid services, have driven this increase in Medicaid expenditures, which contributes to annual deficits and puts pressure on the Federal budget.

- Medicaid was established in 1965, and eligibility was initially tied to receipt of Federal cash assistance for children, low-income families, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities. Reforms in the 1990s severed the link with cash welfare payments and legislation in the 2010s expanded coverage to more low-income adults.

- States have flexibility in designing their Medicaid programs within broad Federal guidelines, leading to wide variation in eligibility, services covered, and the delivery system used for Medicaid benefits.

- In general, Medicaid covers children, pregnant women, adults earning income below a certain level, individuals with disabilities, and individuals 65 years of age and older. Medicaid also has financial eligibility criteria that beneficiaries must meet, and Medicaid eligibility is typically redetermined on an annual basis.

- Medicaid offers comprehensive health care coverage and is the largest payor for long-term services and supports (frequently for the elderly), births, and behavioral health services in the US. State Medicaid programs have increasingly used managed care to deliver these health care benefits, and states have flexibility to develop benefit packages for targeted populations, including those with complex or chronic health care needs.

- Given Medicaid’s financial trajectory, policymakers should consider opportunities for reform, including caps on Federal Medicaid spending, limits on the use of state taxes on health care providers, and adjustments to Federal Medicaid matching rates. Innovative strategies such as value-based care and an emphasis on primary care, preventive care, and coordination of benefits can also assist in improving Medicaid’s fiscal outlook.

Introduction

Medicaid is a joint Federal-State health insurance plan for lower-income Americans and those with limited resources, providing coverage primarily to low-income adults, pregnant women, and children. Medicaid covered 100 million individuals (as of fiscal year 2023, the last year for which data are available) and it is the largest payor of mental health services, long-term care services, and births in the US. Federal law requires states to cover specific eligibility groups and services, and states have the flexibility to include additional groups and covered services under their Medicaid program as well as seek waivers for additional modifications to tailor programs to certain sub-populations or areas within the state.

Medicaid Expenditures and Financing

CBO projected in January 2025 that Federal Medicaid spending will reach $656 billion in fiscal year (FY) 2025, with spending projected at that time to rise to $1 trillion by 2035. This spending increase is projected to occur even as CBO estimated in 2024 that total Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollment would decline from 92 million in 2024 to 79 million people by 2034, in part because of Medicaid redeterminations following the pandemic and in part because of some states’ more restrictive enrollment policies. Medicaid spending has increased for a variety of reasons, including rising US health care costs, coverage expansions, an increase in the number of elderly and disabled individuals requiring more long-term care, increases in provider payment rates over the rate of inflation, and enhanced Federal cost matching under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA).

Figure 1: Total Federal Medicaid Expenditures (1994-2035)

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections (January 2025), Historical Budget Data (January 2025), and Economic Projections (January 2025); The Conference Board, 2025.

Rising health care costs are a feature of the US health care system, and Medicaid is no exception. The US already has the highest health care costs per capita compared to other advanced countries. Higher costs are tied to higher prices for most health care services and prescription drugs compared to other advanced economies—utilization of services is less of a factor because certain services, including physician consultations per capita and the average length of hospitals stays, are lower in the US compared to other advanced economies. Rising health care costs per beneficiary put pressure on the Federal budget, which is already running sustained, record-breaking deficits. To finance this spending, the Federal government will continue issuing debt in the form of Treasury securities, which will in turn increase the costs of servicing the national debt and begin crowding out other spending priorities.

A key feature of the Medicaid program is joint Federal and state financing. The Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) determines the Federal share for most health care services. Per capita incomes in each state form the basis of the FMAP formula, with higher reimbursement going to states with relatively lower per capita incomes. For example, Mississippi’s FMAP is approximately 77 percent in FY2026, and New York and nine other states have an FMAP of 50 percent. Federal law sets a minimum FMAP of 50 percent and a maximum of 83 percent. Exceptions exist for specific populations, services, and providers, with the Affordable Care Act optional expansion population (discussed below) having an FMAP of 90 percent and certain administrative expenses having an FMAP of 75 percent or higher. Importantly, there is no cap on overall Federal Medicaid spending, which varies by enrollment, utilization, and the types of benefits and eligibility groups states decide to cover.

States finance their share of Medicaid expenditures in five ways, sometimes with the financial assistance of local governments and health care entities. States can use their general funds, which hold revenue collected through income and sales taxes and other sources. States can impose health care-related taxes (also known as provider taxes, fees, or assessments) as long as at least 85 percent of the tax burden falls on health care providers or services or if the tax treats health care providers differently than other entities. Health care providers can make voluntary contributions, known as provider donations, to cover the non-Federal share of certain Medicaid expenditures. Public agencies and local governments, including state university hospitals and state psychiatric hospitals, can make intergovernmental transfers to the state. Finally, states and local governments can certify that certain expenditures are eligible for Federal matching funds, known as certified public expenditures.

In FY2018, state funds made up 68 percent of the non-Federal share of Medicaid payments, with provider taxes and donations providing 17 percent and local governments providing 12 percent. Overall, Medicaid expenditures form a significant part of state budgets—roughly 29 percent of state budgets (as of state FY 2022, the last year for which data are available) goes towards Medicaid when all Federal and state funds are included.

Brief History of Medicaid

Congress enacted Medicaid alongside Medicare in 1965, primarily to provide coverage to groups that were historically excluded from obtaining private insurance, such as individuals with disabilities who require long-term services and supports or low-income residents in regions with limited providers or insurance coverage. This legacy means that Medicaid offers benefits that are not typically covered by many private insurers, such as home and community-based services. Medicaid eligibility was initially linked to receipt of aid under the former Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), in existence until 1997, which provided cash welfare payments for needy children receiving limited or no support from their parents. When Congress established the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program in 1972 to federalize cash assistance for the aged, blind, and disabled, these beneficiaries also became entitled to Medicaid coverage. (For those enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid, Medicare is the primary payor and Medicaid the payor of last resort.)

In the 1980s, Congress established Medicaid waivers to allow states to pursue mandatory managed care enrollment of certain Medicaid populations and to cover home and community-based long-term care services upon approval by the former Health Care Financing Administration, now the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Congress also expanded eligibility to all AFDC-eligible pregnant women.

In the mid-1990s, Congress made fundamental changes to the operations of the Medicaid program. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 repealed AFDC and replaced it with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. This law also severed the link between AFDC and Medicaid, so that enrollment in or termination of Medicaid was no longer automatic with the receipt or loss of AFDC cash assistance. In 1997, in the Balanced Budget Act, Congress established Federal matching funds to expand health insurance coverage for children in families with incomes above states’ Medicaid eligibility levels and updated payment policies for managed care and other health care providers.

In the 2010s, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA) expanded Medicaid eligibility to include nearly all individuals under age 65 with incomes up to 133 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius in 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress could not force states to participate in this expansion of Medicaid coverage. Since enactment of PPACA, 41 states (including DC) have expanded Medicaid eligibility at least to some extent under its provisions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress passed temporary FMAP increases to support state budgets and local economies on the condition that states did not disenroll Medicaid beneficiaries. This provision ended March 31, 2023, leading to a process termed Medicaid unwinding, which removed 25 million recipients from state Medicaid rolls as of September 2024, even as enrollment remained higher than before the pandemic. States also took advantage of emergency authorities during the public health crisis to expand use of telehealth and Medicaid eligibility and benefits, as well as address workforce issues for home and community-based services.

More recently, Public Law 119-21 (H.R. 1, 2025), also referred to as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” or OBBBA, made significant changes to the Medicaid program. The Act restricts the ability for states to raise Medicaid provider taxes (discussed more below), requires states to establish Medicaid community engagement requirements (i.e., 80 hours of work, community service, work program, and/or educational program participation per month) for able-bodied adults without dependents, delays implementation until 2035 of the Eligibility and Enrollment final rule that streamlined application and enrollment processes for Medicare Savings Programs and Medicaid, reduces Medicaid state directed payments from the average commercial rate to 100% of the Medicare rate (for PPACA optional expansion states) or 110% of the Medicare rate (for non-expansion states), and enhances eligibility checks while limiting eligibility for lawfully present immigrants. The Act also includes a Rural Health Transformation Program appropriating $10 billion annually for five years ($50 billion total) for states to apply for funding for rural hospitals and other specified rural health facilities (e.g., federally qualified health centers, community mental health centers, and rural health clinics); many of these facilities have a high percentage of Medicaid recipients. Following the enactment of the OBBBA, CBO estimated the Medicaid policy changes in the Act will reduce the deficit by nearly $940 billion between 2025 and 2034 and will increase the number of people without health insurance by 7.5 million by 2034.

Overview of the Medicaid Program

CMS in the Department of Health and Human Services is responsible for overseeing the Medicaid program at the Federal level. Each state administers its own Medicaid program following broad national guidelines established by Federal statutes, regulations, and policies. Medicaid’s actual delivery of benefits relies on a health care system comprising private health plans under contract to state governments, hospitals, physicians, and other medical providers.

Role of States

While participation in Medicaid is voluntary, all states, the District of Columbia, and all US territories have chosen to participate. Medicaid is also an entitlement for states, which means that states are entitled to Federal Medicaid matching funds if they operate their Medicaid programs within Federal requirements. Thus, total spending on a state’s Medicaid program depends both on that state’s policy decisions, including its decisions on eligibility and coverage, contracts with health plans managing Medicaid services, and the utilization of Medicaid benefits by enrollees within that state.

States typically describe how they will operate their Medicaid programs through a state plan approved by CMS. States have discretion regarding how they determine certain eligibility criteria for Medicaid enrollees and may request a waiver of Federal law from CMS to extend health coverage to groups not described in Federal law or to modify how the state’s Medicaid program provides care. States may also target specific benefits to certain groups through various state plan options, use waiver authority to customize benefits to specified Medicaid subgroups, and offer services outside the standard benefit packages. As such, there exists considerable variation across state Medicaid programs.

Eligibility

Medicaid eligibility is determined by several factors: categorical criteria, financial criteria, whether including a group in a state plan is mandatory or optional under Federal law, and the extent of a state’s discretion in determining the eligibility criteria for a group. In general, assuming eligibility criteria are met, Medicaid can cover children, pregnant women, adults earning income below a certain level, individuals with disabilities, and individuals 65 years of age and older.

Figure 2: Total Medicaid Enrollment (FY1973-FY2023)

Sources: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), Exhibit 10, Medicaid Enrollment and Total Spending Levels and Annual Growth, December 2024; The Conference Board, 2024. (Last fiscal year for which data are available)

Federal law requires states to cover certain eligibility groups, known as mandatory categorically needy, which include low-income families, qualified pregnant women and children with annual family income at or below 133 percent of the FPL, children receiving foster care or adoption assistance under Title IV-E of the Social Security Act, and individuals obtaining Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits. States also have the option to cover other groups, known as optional categorically needy, including pregnant women and infants with annual family income between 133 and 185 percent of the FPL, individuals obtaining home and community-based services, and children in foster care who are not otherwise eligible.

Additionally, states can establish a medically needy program for individuals with significant health needs whose income is too high to otherwise qualify for Medicaid. These individuals must “spend down” their income above a state’s medically needy income standard by incurring expenses for medical care, at which point Medicaid pays the cost of medical and other health-related services that exceeds the expenses the individual had to incur to become eligible for Medicaid. One common use of this program is as a safety net for older adults that provides a pathway to qualify for Medicaid to help pay for long-term care.

Two Medicaid eligibility groups are worth highlighting. The PPACA allows states to expand Medicaid eligibility to all nonelderly adults with income at or below 133 percent of the FPL. As an incentive for states to expand coverage to this optional population, the Federal government provides an enhanced FMAP of 90 percent for these individuals. As of August 2025, 41 states (including DC) have adopted this Medicaid expansion.

Some individuals are also eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare, referred to as dual eligibles. This group of individuals is a growing population within Medicaid, with 13.7 million dually eligible individuals enrolled in Medicaid in FY2022, up from 8.6 million in 2006. Dual eligibles may have partial or full Medicaid benefits and Medicaid assists with some or all of an individual’s Medicare premiums and cost sharing. Dual eligibles represent a disproportionate share of Medicaid expenditures because of higher rates of chronic illnesses, significant long-term care needs, and mental health diagnoses, accounting for 32 percent ($244.5 billion) of Medicaid expenditures in FY2022 despite only making up 15 percent of Medicaid enrollees.

Figure 3: Medicaid Enrollment by Major Eligibility Group (FY2022)

Notes: “New Adult Group” refers to PPACA optional expansion population; “Disabled” refers to children and adults under age 65 who qualify for Medicaid on the basis of disability; “Aged” refers to individuals age 65 and older who qualify for Medicaid through an aged, blind, or disabled pathway. (Last fiscal year for which data are available)

Sources: MACPAC, Exhibit 14, Medicaid Enrollment by State, Eligibility Group, and Dually Eligible Status, October 2024; The Conference Board, 2024.

To determine financial eligibility, Medicaid generally uses a methodology based on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI), which considers taxable income and tax filing relationships. The MAGI methodology does not allow income disregards, nor does it allow an asset or resource test. Most children, pregnant women, parents, and nonelderly adults use MAGI to determine their financial eligibility. Individuals whose eligibility is based on blindness, disability, or age (65 or older) use the income methodologies of the SSI program to determine their financial eligibility. Other groups, such as individuals obtaining SSI and children obtaining adoption assistance under Title IV-E of the Social Security Act, do not require a determination of income to enroll in Medicaid.

Once a state Medicaid agency determines an individual eligible for Medicaid, coverage is effective on the date of application or the first day of the month of application. Benefits may be covered retroactively for up to three months prior to the month of application, and coverage stops at the end of the month when a person no longer meets eligibility requirements. Medicaid eligibility is generally subject to annual redetermination. Medicaid beneficiaries must also generally be residents of the state in which they receive Medicaid and must be either US citizens or lawful permanent residents. The OBBBA will require eligibility redeterminations to be conducted every six months starting in 2027.

Medicaid Benefits

Medicaid requires that states provide a collection of mandatory benefits under Federal law. These mandatory benefits include services for inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, physician, nursing facility, family planning, laboratory and X-ray, and Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT). States may also cover optional benefits, such as dental services, physical and occupational therapy, prescription drugs, eyeglasses, and primary care case management.

To deliver these benefits, states offer two primary benefit packages. Traditional Medicaid benefits are packages of mandatory and optional services that are subject to four broad Federal guidelines related to sufficiency of amount, duration, and scope; comparability; statewideness; and freedom of choice. These

guidelines exist to ensure a service reasonably achieves its purpose, is equal across various population groups, is the same statewide, and provides choice among health care providers. States have discretion in the breadth of coverage for a given benefit within these four Federal guidelines.

States also offer alternative benefit plans (ABPs), which provide comprehensive benefit coverage based on a coverage benchmark as opposed to a list of discrete services under traditional Medicaid. ABPs must include the essential health benefits that most private insurance plans cover, EPSDT benefits, family planning services, and transportation to and from health care providers. States may waive the statewideness and comparability requirements under traditional Medicaid to define populations that will be served by an ABP. The Federal government requires that individuals in the PPACA optional expansion population receive ABP coverage.

In general, premiums and cost sharing under Medicaid are limited. States may charge limited premiums to certain groups of Medicaid enrollees, such as pregnant women with family income above 150 percent of the FPL or qualified disabled and working individuals with income above 150 percent of the FPL. States may also charge copayments for prescription drugs and non-emergency use of the emergency department. However, certain groups, such as pregnant women, and services, including preventive services for children, are exempt from cost sharing in Medicaid under the Social Security Act.

Figure 4: Medicaid Spending on Benefits by Major Category (FY2023)

Notes: Excludes collections from Medicaid enrollees; all categories are fee-for-service benefits apart from “Managed care and premium assistance” and “Medicare premiums and coinsurance.” (Last fiscal year for which data are available)

Sources: MACPAC, Exhibit 17, Total Medicaid Benefit Spending by State and Category, September 2024; The Conference Board, 2024.

Medicaid Managed Care

Historically, the Medicaid delivery system has operated on a fee-for-service basis, meaning that state Medicaid programs paid health care providers for each service they delivered to Medicaid enrollees. Since the 1990s, Medicaid has moved towards managed care, in which state Medicaid programs contract with one or more organizations to provide benefits to Medicaid enrollees. These managed care organizations (MCOs), which are private health insurance companies, typically receive payments on a capitated basis. Under capitated payment arrangements, MCOs receive a fixed per member per month prospective payment for each Medicaid enrollee that they cover. MCOs are then responsible for arranging health care services for their Medicaid enrollees and paying health care providers.

As of July 2022, nearly 75 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in comprehensive risk-based managed care, in which enrollees receive a comprehensive package of health benefits from an MCO. Approximately 6 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in primary care case management (PCCM), contracts between state Medicaid programs and primary care providers to provide case management services to Medicaid enrollees. Primary care providers receive a monthly case management fee for each enrollee, though they continue to bill the Medicaid program on a fee-for-service basis for medical care. Medicaid also has limited benefit plans that provide coverage for one or two Medicaid services on a capitated basis, such as behavioral health benefits, dental services, and transportation. Some states, including Hawaii and South Carolina, exclusively provide Medicaid benefits via managed care, while others, including Alaska and Connecticut, do not provide managed care coverage.

Waivers and Long-Term Care

In addition to the flexibilities described above, states have several waiver and demonstration authorities that allow them to experiment with different approaches to deliver health care or tailor programs to the needs of particular populations or geographic areas. States apply to CMS for these waivers, which are time-limited and may be subject to reporting, evaluation, and financing requirements. Each waiver is tied to a specific section of the Social Security Act and allows state Medicaid programs to waive one or more of the four Federal guidelines that govern traditional Medicaid benefits.

A prominent waiver authority is the Section 1915(c) home and community-based services (HCBS) waiver. This waiver allows states to develop programs for individuals who prefer to obtain long-term care services and supports in their home or community as opposed to in an institutional setting. States must demonstrate that the waiver services will not cost more than providing these services in an institution, ensure the protection of a beneficiary’s health and welfare, provide adequate and reasonable provider standards to meet the needs of the target population, and ensure that services follow an individualized and person-centered plan of care. In exchange, states receive a waiver of the statewideness and comparability Federal guidelines and of certain income and resource rules to target services to areas with the greatest need or to certain groups who are at risk of institutionalization, such as the elderly and people with intellectual disabilities. Almost all states operate at least one 1915(c) HCBS waiver.

Another popular waiver authority is the Section 1915(b) managed care and freedom of choice waiver. States can use Section 1915(b) waivers to implement their managed care programs by requiring enrollment in managed care, utilizing a centralized broker for managed care enrollment, using cost savings to provide additional services to enrollees, and/or limiting provider networks. CMS approves Section 1915(b) waivers for two years at a time.

States may also conduct Section 1115 demonstrations to develop experimental or pilot programs with the goal of demonstrating and evaluating state-specific policy approaches to better serve Medicaid beneficiaries. CMS reviews Section 1115 demonstrations on a case-by-case basis, and the applications must show how the demonstrations will be budget neutral to the Federal government. CMS approves these programs for an initial five-year period, which can be extended by an additional three to five years. States have used this authority in a variety of ways, including to expand coverage to new populations, institute work or community engagement requirements, address an enrollee’s housing or other health-related social needs, and offer different combinations of services in different areas of the state. Starting in 2027, the OBBBA prohibits CMS from approving an application for or renewal of a Section 1115 demonstration unless the Chief Actuary for CMS certifies the demonstration is budget neutral to the Federal government.

In general, Medicaid is an important provider of long-term care, also known as long-term services and supports (LTSS), with over 30 percent of total Medicaid spending going to LTSS in FY2020. Medicaid beneficiaries must typically demonstrate the need for LTSS by meeting functional, disease, or condition-specific eligibility criteria set by states. LTSS can be provided in an institutional setting such as a nursing home or in the home or community as is done through HCBS. There are separate financial eligibility rules to obtain Medicaid-covered LTSS regarding limits on the value of home equity and asset transfer rules. Eligibility for Medicaid LTSS generally requires a “spend down” of assets and income to reach asset and income limits for LTSS, which can involve a five-year look-back period of past transfers to prevent the gifting of assets or selling them under market value to qualify for LTSS.

States have three main state plan options to provide LTSS coverage to targeted populations of Medicaid beneficiaries. Section 1915(i) of the Social Security Act, first enacted in 2005, allows states to offer a wide range of HCBS for specific populations, and states can tailor the benefit package by population by adjusting the amount, duration, and scope of services. States can receive increased FMAP to offer community-based attendant services and supports to certain populations who require LTSS by using Section 1915(k) authority, also known as the community first choice state plan option. States can also integrate services and coordinate care for Medicaid enrollees with complex or chronic physical or behavioral health needs through Section 1945 authority, also known as health homes, and can receive enhanced FMAP during the startup phase of this program.

Figure 5: Comparison of LTSS Users and Benefit Spending vs. All Other Medicaid Enrollees and Services (FY2022)

Sources: MACPAC, Exhibit 20, Distribution of Medicaid Enrollment and Benefit Spending by Users and Non-Users of Long-Term Services and Supports, October 2024; The Conference Board, 2024. (Last fiscal year for which data are available)

Medicaid’s Impact

Medicaid has a significant impact on the US health care system, covering more than 20 percent of all Americans. Medicaid covers four in ten children, eight in ten children living in poverty, 41 percent of all births, and nearly half of children with special health care needs in the US, defined as children who “have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral or emotional conditions and also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.” Medicaid also covers almost half of adults living in poverty, five in eight nursing home residents, 23 percent of non-elderly adults with a mental illness, and 40 percent of non-elderly adults with HIV. Medicaid is the largest payor of LTSS and behavioral health services in the US and a key source of financing for certain providers such as federally qualified health centers, rural health clinics, and Indian Health Service facilities.

Medicaid’s impact is reflected in the program’s popularity across party lines. While Democrats and independents are more likely to view Medicaid favorably than Republicans, 29 percent of respondents in a 2023 poll held a very favorable view of the program and 47 percent held a somewhat favorable view of the program. The Medicaid PPACA optional expansion is also widely popular, so much so that seven states (Iowa, Maine, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Utah) have adopted the expansion via ballot measure, with voters effectively overriding state legislatures that refused to expand Medicaid eligibility. Two-thirds of respondents in non-expansion states including Texas and Florida want their state to expand Medicaid, demonstrating the value of Medicaid to many Americans.

Opportunities for Reform

Given the expected increase in Medicaid expenditures amid the Federal government’s sustained deficits, Congress should consider a comprehensive package of reforms through bipartisan negotiations to set Medicaid on a more sustainable fiscal path, which a bipartisan Fiscal Commission could facilitate.

Congress should also protect vulnerable populations of Americans by gradually phasing in any legislative changes to provide Medicaid enrollees, health care providers, and health insurers sufficient time to adjust. CBO, the nonpartisan agency that produces independent analyses of budgetary and economic issues to support the Congressional budget process, has described three options that would produce large reductions to the deficit. Policymakers should consider the tradeoffs from these policies to balance the decreases in spending with increased costs for states and health care providers and potential reductions in access to Medicaid services.

One policy option is caps on Federal Medicaid spending. These caps could be to overall spending, which would not be tied to changes in enrollment, or to per enrollee spending, which would make total Federal funding vary according to enrollment. In December 2024, CBO modeled these two types of caps alongside two potential growth rates based on the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Over ten years, overall spending caps would produce a net decrease in the deficit of $742 billion (with growth based on CPI-U) and a net decrease of $459 billion (with growth based on CPI-U plus one percentage point). Over a decade, caps on spending per enrollee would provide a net reduction in the deficit of $893 billion with growth based on CPI-U and a net reduction of $588 billion with growth based on CPI-U plus one percentage point. Policymakers have flexibility in selecting spending and eligibility categories, the base year, and the specific growth factor to balance this option’s tradeoffs.

Another policy option is to limit state taxes on health care providers. States in the late 1980s and early 1990s established taxes on health care providers that held providers harmless by returning funding to them in the form of higher Medicaid payments, with states pocketing additional revenue through Federal matching payments. To limit this practice, Congress prevented these “hold harmless” arrangements unless a state collects taxes at a rate that is less than six percent of a provider’s net revenues from treating patients. In December 2024, CBO modeled three changes to the threshold for this “safe harbor” exception over a ten-year period: 1) lowering it to five percent produces a net reduction in the cumulative deficit of $48 billion; 2) lowering it to 2.5 percent produces a net reduction of $241 billion; 3) and eliminating hold harmless arrangements would result in a net reduction of $612 billion. The OBBBA reduces the hold harmless threshold for provider classes other than nursing or intermediate care facilities by 0.5 percentage points annually starting in FY2028 until reaching 3.5 percent in FY2032, which CBO estimates will reduce the deficit by more than $190 billion over the next decade. Currently, 38 states have at least one provider tax over 5.5 percent of net patient revenues.

Finally, CBO analyzed in December 2024 the effects of reducing Federal matching rates on the deficit by modeling three scenarios. Reducing the Federal matching rate for certain administrative costs from 70-100 percent to the standard 50 percent would reduce the deficit by $69 billion over 10 years. Removing the FMAP floor of 50 percent would reduce the FMAP for the states with the highest per capita incomes to between 4 percent and 49.75 percent, resulting in a decrease in the deficit of $530 billion over 10 years. Aligning the current 90 percent FMAP for the PPACA optional expansion population with the FMAP for other Medicaid enrollees would produce a net decrease in the deficit of $561 billion over 10 years. In every scenario, states would have to backfill the loss of Federal funding with state funds or consider changes to Medicaid eligibility and benefits.

An innovative strategy to modernize Federal health programs is value-based care, which can be combined with alternative payment models to move away from a delivery system based on fee-for-service reimbursement. In practice, value-based care, which is increasingly used for Medicare and in commercial health insurance, means coordination and collaboration between physicians and other providers to focus on quality of care, provider performance, and the patient experience. To realize fully the potential of these innovative strategies, the Federal government, hospitals, and other medical providers should make the appropriate upfront investments in the health care workforce and data infrastructure. This will produce benefits throughout the US health care system, not just the Medicaid population.

In addition to value-based care, encouraging primary care, preventive care, and care coordination often leads to improved health outcomes throughout the health care system and potentially saves money for the health system in the long run by reducing the cost of care. This is true in particular for Medicare if these types of interventions are introduced earlier in a beneficiary’s life so that beneficiaries enter Medicare either healthier or already under treatment for chronic conditions. Similarly, interventions such as immunizations, promoting healthy lifestyle choices, and regular health screenings help reduce costs by preventing hospitalizations and identifying health conditions early. Private health insurers are increasingly employing care coordinators to assist their enrollees, and Medicaid has approved care coordination waiver programs in which dedicated staff assist patients with coordinating health care services. More broadly, the Administration and Congress should also assess strategies to streamline regulations and payment policies that are adding costs and administrative burden to the health care system.

Conclusion

Medicaid is a crucial health insurance program for low-income Americans, individuals with disabilities, and many seniors in long-term care. Together with Medicare, it accounts for the vast majority of Federal health spending. Given rising Federal health care costs and unsustainable Federal budget deficits, it is vital that Congress address Medicaid’s fiscal trends quickly to allow for adequate time to phase in changes to Medicaid. The longer the delays, the greater the chance that necessary legislative changes to preserve Medicaid will be disruptive to beneficiaries, health care providers, and the broader economy.

For Further Reading

- CED’s Solutions Brief, Modernizing Health Programs for Fiscal Sustainability and Quality, November 18, 2024

- CED’s Explainer, Medicare, August 2025

- CED’s Explainer, US National Debt, August 2025

- CED’s Policy Backgrounder, “Health Care Policy Update,” May 17, 2024

- “The Debt Crisis is Here,” Dana M. Peterson and Lori Esposito Murray, November 13, 2023