The precise role of corporate citizenship varies by company, as does its position in each an organization. Generally speaking, however, corporate citizenship continues to focus on how a company conducts itself in a manner that promotes the welfare of society.

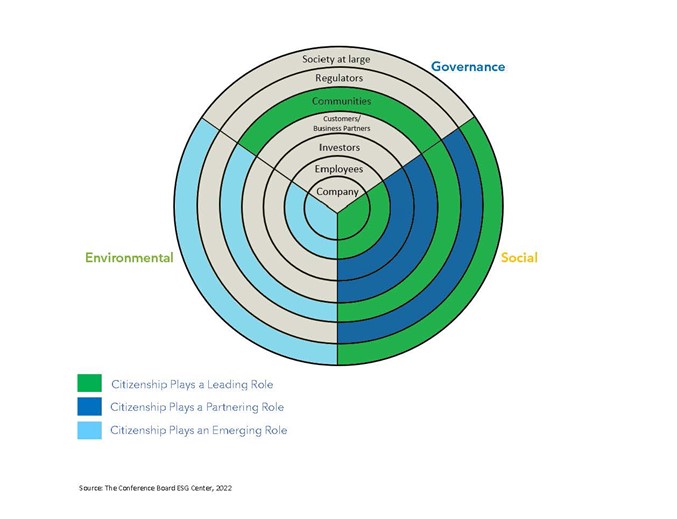

The chart below illustrates how corporate citizenship can map against ESG issues for the company’s stakeholders. Of the three ESG areas, corporate citizenship tends to focus mostly on social issues; it plays only an emerging role on environmental issues; and its role in governance is usually limited to managing any entities that are directly responsible for community engagement (e.g., community advisory boards).

In terms of stakeholders, citizenship tends to focus on the company’s impact on communities and society and, often in partnership with other functions, on employees and customers. Finally, it tends to have more hands-on experience in directly executing programs and deeper expertise in areas such as corporate philanthropy and employee volunteering.

Given the evolving role of corporations in serving the long-term welfare of multiple stakeholders, with a particular emphasis on community, we can expect that corporate citizenship will play an increasing role in responding to a broad array of social and environmental issues, as well as in supporting the execution of corporate business strategies.

Insights for What’s Ahead

Expect CEOs to play a greater role in their company’s corporate citizenship activities. CEOs recognize that evolving stakeholder expectations about the role of business in society will have a substantial impact on their business,[2] so it’s not surprising that most of the participants in our roundtable expect the level of engagement of their CEO with corporate citizenship to increase. As CEOs view corporate citizenship as a key tool in addressing both the “S” and “E” in ESG—and as an important way to retain, attract, and motivate employees—they are likely to become more involved in oversight, decision-making, and direct engagement with communities.

As corporate citizenship is becoming a more important element in corporate business and ESG strategies, look for increased board involvement as well.[3] Most of the corporate citizenship professionals we spoke with expect their level of engagement with their corporate board to increase. We are already seeing an increase in board committees focusing on ESG, CSR, and public responsibility. To be most effective, management should not present information about corporate citizenship to the board in a siloed manner, but should incorporate information from other board materials and discussions; it’s also important to present information not to garner applause for good work, but in a way that elicits constructive feedback from directors on how to optimize the company’s citizenship programs.

Companies should embrace the fact that corporate citizenship serves multiple purposes and stakeholders; when deciding where the function should sit, the key is to place it within an organization, and at a level, where it can effectively serve, collaborate with, and leverage multiple other functions at a company. Executing the company’s citizenship strategy will require governance practices that harness resources from across the organization. Corporate citizenship executives recently cited lack of time, funding, and staff as the biggest obstacles to achieving their goals for 2022.[4] While adding members to typically small corporate citizenship teams can help, successfully advancing the company’s business and citizenship strategies will involve greater engagement with other corporate departments and business units, leveraging their resources. This, in turn, will require governance practices that provide for informed decision-making and clear accountability, oversight of the firms’ citizenship strategy, complying with applicable regulations, protecting the company’s reputation, and stakeholder communication and engagement.

Companies should ensure that corporate citizenship works closely with both sustainability and diversity, equity & inclusion (DEI). In the most expansive view of corporate citizenship, everything a company does to behave in a responsible manner, including efforts toward advancing the long-term welfare of the company, its stockholders and other stakeholders, society, and the natural environment, can be said to fall within this function’s purview. And the function’s long-standing expertise in volunteerism and philanthropy make it the natural management and governing body for community-minded employee resource groups. At a minimum, corporate citizenship, sustainability, and DEI should pool their resources when identifying social issues for the company to address. Each of these functions brings particular expertise to bear in representing the views of key stakeholders in addressing common social issues: broadly, corporate citizenship can be said to represent the voice of the community, sustainability the voice of the investor, and DEI the voice of the employee. As each of these disciplines is also stretched thin and has skills or data that at least one of the others can use, all can better manage time and resources by collaborating as part of a deliberate process rather than ad hoc.

As corporate citizenship is increasingly integrated with the company’s business strategy, it can be helpful to have a steering committee led by corporate citizenship and including other functions (sustainability, legal, finance, communications, business units) to formulate the company’s citizenship strategy for CEO and senior management review. Including multiple stakeholders in the decision-making process strengthens the connections between citizenship and corporate functions and business units, helps build greater understanding of and support for citizenship initiatives, and enhances the ability to identify risks and opportunities. It also helps corporate citizenship professionals both build their skill set and gain deeper understanding of their company’s business. It is helpful to have a charter to govern the steering committee with clearly agreed responsibilities to ensure efficient decision-making.

Inviting community leaders to speak to the corporate citizenship steering committee, while it may involve some initial unease, is one way to collaborate with community stakeholders in defining problems, identifying goals, and developing solutions. Including community voices as part of the company’s process for developing its strategy and programs can help foster open and honest dialogue about what nonprofit organizations truly need, thereby improving the likelihood of positive outcomes.[5]

Companies (and society) can benefit from a combination of grants made from corporate funds through the annual budgeting process as well as from giving through corporate foundations, but firms should periodically evaluate the costs and benefits of each mode of giving. Direct corporate giving is often better suited to supporting initiatives that are closely linked to the company’s business. Because it is subject to the annual budgeting process, direct giving can help increase CEO and senior management buy-in and, depending on the firm’s financial resources, result in broader, more sustained commitments to corporate citizenship programs than giving through a foundation could achieve. Giving through a corporate foundation, on the other hand, can allow funding of long-term grants without the full expense hitting the corporate books in a single year. It is also a good source for matching employee gifts, and its separate status helps reinforce the message that grants are made for the benefit of the recipients, not of the company. Some companies are finding that the incremental costs associated with maintaining a foundation outweigh the benefits. And given certain legal restrictions that can limit a foundation’s ability to work with a company, firms should periodically assess whether it makes sense to maintain one.

Many companies have been centralizing their corporate citizenship budgets and, as the level of alignment between corporate citizenship and corporate strategy increases, we expect this trend toward centralization to continue. Fifty-four percent of the corporate citizenship professionals who responded to our 2021 survey indicated that their department operates within a hybrid model: both a centralized budget managed by corporate headquarters and budgets embedded within and managed by regional or business unit budgets. While placing some budgetary control in the business units and regions can mean more targeted and effective philanthropy, it can also lead to inefficiency and a lack of corporate-wide coordination. Whichever budget model corporate citizenship departments use, they should focus on achieving both efficiency and effectiveness, and ensure that business unit and regional philanthropy is in sync with corporate’s.

Companies should govern and manage corporate citizenship in a way that enables them to attract, retain, and motivate employees. A common way for companies to engage employees in corporate citizenship efforts is through volunteering; employees often mention in engagement surveys that they feel proud knowing the company they work for is a good corporate citizen and that their own actions contribute to that citizenship.[6] And the benefits of employee engagement with communities can go deeper than that: as communities come to trust the employees working among them, they also trust the company itself; a three-way stickiness occurs between the company, its employees, and the community, with engaged employees as the glue. At the same time, the connections between corporate citizenship and employees can run deeper than volunteering and employee engagement. Corporate citizenship departments should have processes in place to ensure that they are coordinating effectively with their human resources counterparts on areas of shared interest, such as DEI. It’s also helpful for corporate citizenship, HR, and the company’s business leaders to coordinate their engagement with employee resource groups, and to leverage those groups in informing and executing their strategies.

As companies move toward more innovation in corporate citizenship, their governance processes will need to keep pace. Companies are increasingly moving beyond traditional modes of corporate citizenship (cash donations, in-kind contributions, and employee volunteering) to other arenas, including helping to build minority- and women-owned suppliers, investing in socially oriented for-profit entities, and providing no-interest loans to entities. In many cases, corporate citizenship departments take the lead; in others they are the catalyst, convener, consultant, or supporter. But in every case, it’s critical for the company to have clear criteria for deciding which areas to focus on and the objectives of such investments (whether financial or social).

Corporate citizenship leaders will increasingly be expected to measure and report on the impact of their initiatives as part of their overall disclosure practices. To date, shareholder proposals urging companies to be more forthcoming about the direct recipients of their charitable giving funds—or to otherwise be more transparent—have not gained much traction.[7] Further, companies may have a harder time measuring the positive impact of corporate citizenship efforts than they do measuring carbon emissions. But it is nonetheless important for companies to provide both qualitative and quantitative measures of impact. Companies should not underestimate the power of a narrative to convey impact to current and prospective employees, customers, communities, regulators, and investors. And benchmarking corporate citizenship goals against similarly situated companies can be one step on the journey to quantitative impact measurement. ESGAUGE’s Human Capital and Social Practices Benchmarking Tool and Impact Genome Project’s Price of Impact Index both offer avenues for assessing social impact.[8] Perhaps most importantly, however, effective disclosure can also be a powerful tool in leading to more effective governance and management of corporate citizenship resources.

About This Series

As corporate citizenship’s role evolves, so should its governance.[9] This series of three reports offers guidance on the governance and management of corporate citizenship based on the proceedings of The Conference Board Corporate Citizenship & Philanthropy Councils’ discussion group, which held regular sessions over a six-month period in 2020; on a June 2021 roundtable The Conference Board Governance & Sustainability Center held (81 attendees representing 61 companies); related surveys; and external research.

[1] The Conference Board tends to use the term “corporate citizenship” rather than “corporate social responsibility” or other names, as “corporate citizenship” is more globally accepted.

[7] Shareholder Voting Benchmarking Platform, Proxy Seasons 2018-2022, ESGAUGE, 2022.