War in Ukraine: A View from Germany

I was born and grew up in a small rural village in central-western Germany. In many ways, my family’s roots are shaped by war and migration experiences—and the associated hardship as well as opportunities. My mother is a German-turned-American, who as a young child emigrated from post-World War II Germany to the US with her family, in search of a brighter future. My father is German, as are my late grandmothers and grandfathers, both WWII veterans. When getting married and settling in Germany, my parents decided to keep both citizenships in the family. As children of the Cold War era, they wanted us to have access to different parts of the world, just in case. This always sounded far-fetched to me, until February.

My research for my doctorate brought me to the US. My ten-week research visit at Cornell University has turned into more than twenty years in the US. Throughout this time, I’ve kept in close contact with Germany through my family, friends, the media, and regular visits.

When it comes to the view on the war in Ukraine from Germany, three dimensions stand out: the dependency on Russian gas, the intention to rearm the country, and the attitude of consumers vis-à-vis the mounting inflation.

Germany’s “role” in the Russia-Ukraine conflict: envisioning a future without energy from Russia

How can Europe’s largest economy keep running at a time of energy and grain shortages when it runs on cars, bread, and beer? While Germany’s bakeries, households, and wheat beer breweries seem to have enough wheat for now, Germany has been in the spotlight for its significant dependence on Russian energy: it gets almost a third of its overall energy—55 percent of its gas—from Russia. Therefore, Germany’s energy decisions have not only big economic significance but also political importance for Germany as well as the European Union.

Efforts to reduce German dependence on Russian energy

In 2021, almost a third of Germany’s overall energy demand was covered by Russia: gas (55 percent of total gas used came from Russian sources), oil (34 percent), and coal (26 percent).

Given the war, Germany and the EU are trying to reduce—and ideally cut altogether—the energy supply they receive from Russia. The current EU sanctions on Russia include an embargo of Russian coal, and the EU is now discussing further energy sanctions, including an embargo of oil. The sanction-induced cuts of supply have caused energy prices to rise. The German government has responded by reducing the sales tax on car fuel, a one-time reduction of 300 Euros for income taxes and financial aid for heating costs for low-income households.

The big question is whether Germany (and the EU) could do completely without Russian energy. While Germany could get coal and oil from other countries, replacing Russian gas is much more difficult. Russia could initiate a shut off as a retaliatory move, as just happened to Poland and Bulgaria after not meeting Russia’s new demand to pay gas in rubles. However, the ifo Institute estimates that in the case of an immediate shut-off of Russian gas, the gas supply gap could be filled by gas from other countries such as Norway, the Netherlands, Qatar, and the US, and by using coal and nuclear energy for electricity production. But this would still leave a shortfall of about 30 percent of gas or about 8 percent of total energy consumption, requiring significant energy saving, which Germany’s economic secretary has already asked both businesses and consumers to do. Higher taxes on fossil fuel (gas, oil, coal) could be an additional incentive to save energy. The German central bank estimates that ending Russian gas imports, a third of which are used by industries such as steel and pharma, could reduce Germany’s GDP by 5 percent, potentially causing a recession and further inflation. (For comparison, Germany’s drop in 2020 GDP due to the pandemic was 4.5 percent.)

Another important route to cover energy demand is to foster the transition to renewable energies such as wind, biomass, solar, and hydro—especially appropriate for Germany which has been called “the world’s first major renewable energy economy,” and a global leader in renewable energy. This is also due to Germany’s historically greater focus on the environment. Initiated in 1990 and driven further by the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, Germany passed comprehensive legislation in the late-2010s, called “Energiewende” (energy turnaround), to promote carbon-free, eco-friendly, efficient, and reliable energy production and meet total energy demand by renewable energy to at least 60 percent by 2050. Plans included the shutdown of nuclear power plants by 2022 and coal-fired ones by 2038.

The Russia-Ukraine war has increased interest in renewable energy by German consumers and investors. An accelerated, war-inspired transition to clean energy in Germany—analogous to the pandemic-accelerated digitalization—might also help other countries to follow suit. Among the current challenges to accelerate Germany’s energy transition are bureaucratic hurdles of policies, including complex authorization processes, government approvals, and lack of land earmarked for the production of renewable energy.

Germany’s war experiences have shaped pacifist attitudes and restrained patriotic fervor

The other major topic of discussion in Germany since the start of the war in Ukraine has to do with rearming the country. Germany’s experience of the vast loss of life and destruction of World Wars I and II has been a key source of its pacifist culture and its history of demilitarization. Germany’s general policy is to only involve itself militarily for humanitarian reasons but not for political ones, sometimes to the frustration of allies.

Against this backdrop, Germany’s abrupt turn on its demilitarization policy just days after the initial Russian invasion of Ukraine was a stark departure of its post-WW II posture. Apart from immediate special funding of €100 billion ($110.6?billion) for the German military, defense spending will be raised to up to 2 percent of Germany’s GDP, in line with NATO guidelines.

In addition, shortly after the war started, the German government agreed to supply Ukraine with military equipment from its own stock. It recently promised to provide additional supplies. However, the amount is a fraction of the US’s military support and is also smaller than that of the UK, Italy, and Estonia, for example. According to a recent YouGov poll, Germans are divided on supplying Ukraine with heavy arms.

Germany’s history of Nazism has caused significant restraint in displaying patriotism or national pride overtly. This changed only during the 2006 soccer World Cup, which Germany hosted. It was a new sight to see German flags everywhere. Since then, nationalist sentiment has still been restrained compared to other countries. My German experience makes me wonder how future Russian generations might handle their country’s history.

Over the past decade, Germany has gained a lot of experience with immigration, especially from the 2015-16 influx of more than a million Middle Eastern immigrants. In a way, the challenges and societal debate back then have prepared the country for the current arrival of Ukrainian war refugees, which overall has been well accepted, for a variety of reasons. Germany has welcomed more than 360,000 Ukrainian refugees (as of April 22), according to official immigration numbers, but the actual number may be higher. The EU has granted Ukrainian refugees the right to stay and work for up to three years and move freely within the EU. After entering the Schengen area through Poland, Hungary, or Slovakia, a portion of Ukrainian refugees may have continued on to Germany due to social connections or other reasons.

Germans’ enthusiasm for saving meets record inflation

Savings will play a central role in cushioning European consumers from the impact of higher inflation due to the war in Ukraine. Germans might be well prepared given that they are famous for their frugality, which is rooted, at least partly, in the dire economic situation following the two world wars. A 2018 survey explains the Germans’ psychology behind their focus on saving: it gives them a sense of independence, freedom, and happiness. Eighty percent said that it is calming and creates relaxation, and 61 percent said that it makes them happy.

The saving mentality can pay off at times of record-high inflation, which has hit Germany just like the rest of the world. The year-over-year inflation rate was 7.3 percent in March (12.3 percent for goods, 2.8 percent for services)—much higher than the 3.6 percent salary increase in Q4 2021.

A YouGov survey from March found that 90 percent of respondents were “concerned” and 53 percent “very concerned” about the increased prices of goods and services, up from 44 percent just a couple of months earlier. Germans worry more about increased energy prices (90 percent) than about increased food prices (80 percent), according to a GfK study from March. Around 15 percent barely get by financially.

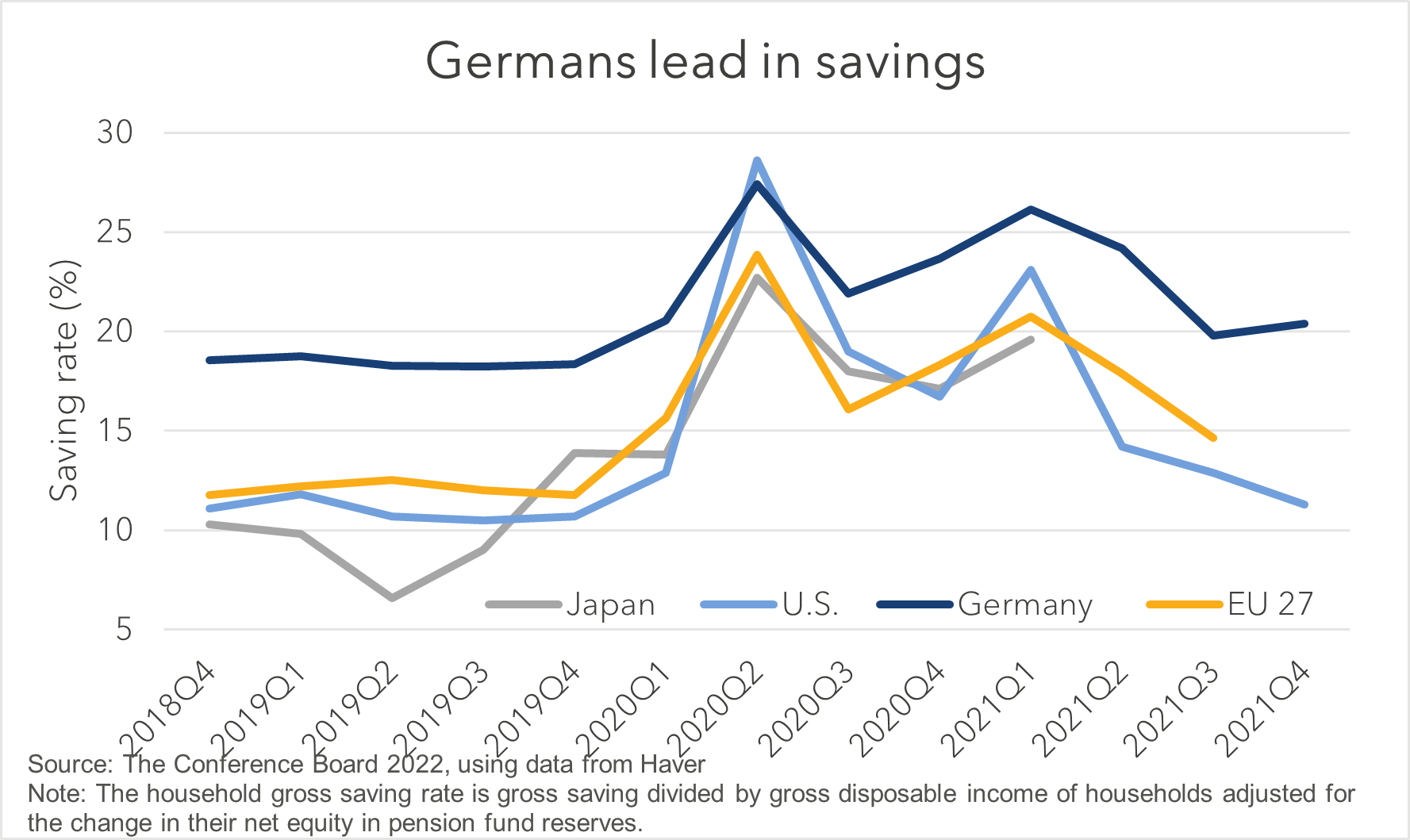

Historically, Germans’ saving rate has been significantly higher than that of other countries, as the chart below shows. The spikes in savings during the pandemic are due to the limited spending caused by lockdowns as well as governmental support payments.

The question is how Germans’ spending, including spending for basics such as energy and food, will develop in the face of record prices. Given Germans’ longer-term thinking and the uncertainty of how long the inflationary period will last, Germans are unlikely to just live off their higher savings and continue consuming as usual.

Indeed, consumer sentiment has dropped significantly since February, and people’s inclination to buy bigger ticket items is close to record lows.

Two thirds of Germans say they are reducing their expenses, especially on energy. Ipsos research found that two-thirds dress for colder temperatures to save on heating, and more than a third—and almost half of households with kids—buy more frequently at discount stores. (It’s no coincidence that Aldi and Lidl are from Germany, a country that loves discounters no matter the economy). Almost four out of ten have reduced their shower time. A third have stockpiled goods affected by shortages such as flour and cooking oil.

Even more significant are the changes in how people use their cars: around three-quarters have changed their way of driving and switched to walking or biking for short distances. Two-thirds are even canceling trips with their cars, and a third use public transportation more.

The expected decrease in domestic demand resulting from the cautious behavior of households adds to the challenges of supply chains and input prices for the German economy. Before the Russia-Ukraine war, and with the relaxation of Covid-19 restrictions, The Conference Board anticipated 2022 GDP growth for Germany of 3.5 percent and 2.9 percent as of January and February, respectively. However, the conflict has reduced this estimate to 1.7 percent as of April, much below the 2.8 percent anticipated growth for the Euro Area, indicating the significant GDP impact of the war on Germany.