The Agility Factor: What Organizations Can Learn From the Beatles

12 Aug. 2014 | Comments (0)

![]()

I’ve been studying organization change and effectiveness for more than 40 years. Recently, the word agility has been the latest buzzword in boardrooms, management retreats, and leadership development programs. There is a lot of research on agile software development, adaptive leadership, and flexible manufacturing, but there is little research on what it means to be an agile organization, how they are organized and operated, and whether such an organization pays off in performance. I’ve asked Chris Worley, colleague and co-author of our new book, The Agility Factor, to write about his seven year study of agility. His response follows. (Full disclosure – I am a partner in the research.)

The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band changed the way people think about music; it is regarded as one of the most pivotal music releases of all time. Pop star, Phil Collins, said that it opened a door and showed people a new room.

Yet, the door had already been opened for the Beatles. Paul McCartney said that the single biggest influence on Sergeant Pepper was the Beach Boy’s Pet Sounds album. The Beatles’ awe of Brian Wilson’s creativity challenged them to match sounds from bass harmonicas, sitars, and French horns to create wholly new musical textures and songs.

The topic of agility fills boardrooms, management retreats, and leadership programs, yet an internet search reflects the confusion over what it actually means. You are more likely to get information about dog training and software development than anything related to how organizations can be more flexible, nimble, and adaptable.

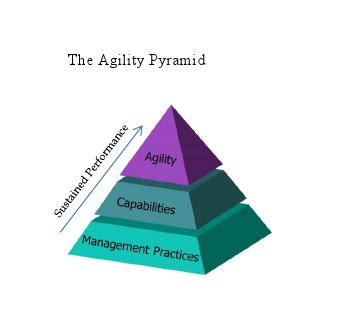

T o help corral misunderstandings, we developed the Agility Pyramid. It helps to explain the success, not only of Sgt. Pepper, but the Beatles’ long term success. Sitting on top of capabilities and management practices, agility is the ability to make timely, effective, and sustained organization changes. It is defined by four routines: the capacity to (1) strategize in dynamic ways; (2) accurately perceive changes in the external environment; (3) test possible responses; and (4) implement a variety of changes. The agility routines help organizations play and win a dangerous game. These practices help businesses keep focused on the differentiated capabilities that drive above-average performance today, and are powerful enough to find and implement the capabilities that will be needed in the future.

o help corral misunderstandings, we developed the Agility Pyramid. It helps to explain the success, not only of Sgt. Pepper, but the Beatles’ long term success. Sitting on top of capabilities and management practices, agility is the ability to make timely, effective, and sustained organization changes. It is defined by four routines: the capacity to (1) strategize in dynamic ways; (2) accurately perceive changes in the external environment; (3) test possible responses; and (4) implement a variety of changes. The agility routines help organizations play and win a dangerous game. These practices help businesses keep focused on the differentiated capabilities that drive above-average performance today, and are powerful enough to find and implement the capabilities that will be needed in the future.

Strategizing involves creating a climate where shared purpose, identity, and intent can be achieved. By 1967, and in the aftermath of deciding not to tour any longer, the Beatles were trying to figure out how to make a different kind of music within their unique culture, brand, and reputation. In terms of perceiving, they were visiting fairs, small cities (the lyrics to “For the Benefit of Mr. Kite” came from a poster in a small store), and different countries looking for new ideas. They were clearly paying attention to other artists, and were discussing their ideas with their managers, producers, as well as each other. Hearing Pet Sounds helped translate that intent into reality. To get Sergeant Pepper done, they had to test out and experiment with a variety of ideas and ultimately implement and execute the ones that worked. Thus, all four of the routines of agility were in play.

In The Agility Factor, we found that when organizations practice 3 or 4 of these routines, they were 7 times more likely to post above-average profitability over long periods of time.

However, the agility pyramid suggests that there is more to sustaining high-performance than just the four routines. In the middle layer of the pyramid, capabilities describe what an organization can do, and what differentiates agile firms is that they can change their capabilities when and where it creates a performance advantage. At the risk of oversimplifying, if an organization can do things better, faster, or cheaper than their competitors, it is able to achieve above-average performance. Even in the early days, the Beatles’ playing, singing, performing, and managing was better than average.

Sergeant Pepper required The Beatles to develop new capabilities. They learned new skills. George Martin, the group’s producer noted that, “When I first met them, they really couldn’t write a decent song. The best they could give me was “Love Me Do,” and yet, they blossomed as songwriters in a way that was breathtaking.” They also developed new ways of working. Paul described the shift from creating just another catchy single to packaging a set of ideas into an album. Finally, they had to learn to do all this in real time. It required lots of practice along with a fair number of both small and large failures. That’s how you build new capabilities.

When organizations are successful, there is a strong motivation to protect their way of working from imitation, or to defend a competitive advantage. In the case of music, many bands with a successful sound hurry to make the next album. More often than not, such a move may generate short-term benefits, but the band ends up in a same-sounding rut. The cruel joke is that in attempting to preserve an advantage, organizations, like musicians, often overcommit to a recipe and doom their future. The Beatles never fell for that. Before Sgt Pepper there was Rubber Soul and Revolver; after Pepper there was The Beatles (White Album) and Abbey Road.

At the base of the pyramid are the management practices – setting goals, developing budgets, and rewarding people – that support the effective execution of capabilities. Both agile and non-agile organizations may manage well, but in agile firms there is a twist. Goal setting occurs more frequently, incentive systems more flexibly reward execution, change, and the right kinds of behaviors, and resource allocation more flexibly balances short- and long-term horizons. Most importantly, agile firms define leadership as an organization capacity, not an individual trait. Good management in agile organization creates a climate where anyone in the organization is capable of influencing change.

Traditional organizations, with their annual budgets, annual performance appraisals, merit-based pay systems, siloed structures, and hierarchically-defined leadership, not only constrain the ability of the agility routines to shift capabilities, they make everyday changes difficult. Innovation, experimentation, and responses to market opportunities can be held hostage to an annual timetable and “it’s not in the budget” decisions.

The Beatles’ used flexible management practices that changed over time to help them sustain high performance. Their group-based incentives, especially between Lennon and McCartney, spurred creative competition. Moreover, leadership was diffuse. Each member’s cultural and political views influenced the band’s direction. The ability of agile firms to execute and change their most basic management practices allows these firms to change capabilities and support execution of the routines of agility.

Sadly, The Beatles’ arc was short, yet between 1960 and 1969, they produced more #1 hits and sold more albums than any other band. Some of their record achievements still stand. In no small way, they changed the world. The Agility Pyramid helps to explain their success and provides for-profit firms a model for improving their agility.

View our complete listing of Strategic HR blogs.

-

About the Author:Edward E. Lawler III

Edward E. Lawler III is Distinguished Professor of Business and Director of the Center for Effective Organizations in the Marshall School of Business at the University of Southern California. He …

0 Comment Comment Policy