On Governance is a series of guest blog posts from corporate governance thought leaders. The series, which is curated by the ESG Center research team, is meant to serve to spark discussion on some of the most important corporate governance issues.

Directors should be asking for information on the effectiveness of risk management processes. Good practice risk oversight due diligence guidance clearly says they should. Evidence suggests many boards have not been. Why not?

In 2000, after another perfect storm of colossal corporate governance breakdowns, the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) changed the international professional practice standards and said internal auditors should report to boards on the effectiveness of risk management processes. Evidence suggests a large percentage of auditors ignored the new IIA “should-do” standard. In 2010, following the Global Financial Crisis, IIA Global changed the words in the standard from “should” to “must” assess effectiveness of risk management and provided the following interpretation.

Determining whether risk management processes are effective is a judgment resulting from the internal auditor’s assessment that:

- Organizational objectives support and align with the organization’s mission.

- Significant risks are identified and assessed.

- Appropriate risk responses are selected that align risks with the organization’s risk appetite.

- Relevant risk information is captured and communicated in a timely manner across the organization, enabling staff, management, and the board to carry out their responsibilities.

Evidence suggests that since this IIA standard was first enacted almost 20 years ago, a large percentage of Chief Audit Executives (CAEs) have not provided clear opinions to their boards on the effectiveness of their company’s risk management processes. Recognizing the magnitude of this problem, IIA Global has just released new “supplemental” guidance in the hope that more IIA members around the world will comply. (see this site for details)

Given most CAEs are rational and educated people that usually work particularly hard to respond to requests from CEOs and audit committees, it would seem that the number one reason internal auditors haven’t been providing opinions on risk management frameworks is simply that boards of directors haven’t asked for one. An obvious question is “Why not?”

Reason Number 1: Most authoritative guides don’t say boards should ask the company’s Chief Internal Auditor for an opinion on the effectiveness of risk management processes

In 2009, just after the Global Financial Crisis, the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) released some very good guidance for directors via one of their “Blue Ribbon Commissions” reports. It was the best guidance I had seen at the time:

|

While risk oversight objectives may vary from company to company, every board should be certain that:

- The risk appetite implicit in the company’s business model, strategy, and execution is appropriate.

- The expected risks are commensurate with the expected rewards.

- Management has implemented a system to manage, monitor, and mitigate risk, and that system is appropriate given the company’s business model and strategy.

- The risk management system informs the board of the major risks facing the company.

- An appropriate culture of risk-awareness exists throughout the organization.

- There is recognition that management of risk is essential to the successful execution of the company’s strategy.

Source: Report Of The NACD Blue Ribbon Commission, Risk Governance: Balancing Risk And Reward, October 2009

|

What isn’t stated, at least not clearly, is that a simple way to meet these expectations would be to ask the company’s Chief Audit Executive and/or the Chief Risk Officer and/or an outside independent risk management expert for an opinion each year on how the company is doing on each of these NACD risk management “effectiveness” criteria.

In January of this year, 10 years after the NACD issued the guidance above, the NACD released more guidance for directors on how to oversee risk management frameworks. The risk management “effectiveness” criteria have shifted and now put more emphasis on “embedding” risk management in the lines of business and core processes and differentiating “disruptive risks” from “day-to-day risks”:

|

Given the pace of change experienced in the industry and the nature and relative riskiness of the organization’s operations, does the board understand the quality of the ERM process informing its risk oversight? How actionable is management’s risk information for decision making? Does ERM effectively capture and assess early warning signals that indicate more unusual or disruptive risks on the horizon? These and other questions focus on the robustness and maturity of the risk-management process. Directors should ensure that the critical attributes of risk-oversight excellence are present:

- Critical and potentially disruptive enterprise risks are differentiated from the day-to-day risks of managing the business so as to focus the dialogue on the risks that matter to the C-suite and the board.

- Accountability is established for both traditional and disruptive risks and clearly embedded in the lines of business and core processes.

- Actionable new risk information is not only reported up but also widely shared to enable more informed decision making.

- An open, positive dialogue for identifying and evaluating opportunities and risks is encouraged. Consideration should be given to reducing the risk of undue bias and groupthink so that adequate attention is paid to differences in viewpoints that may exist among different executives.

- Advancements in the application of new technologies—including AI, machine learning, mobile technologies, advanced data analytics, and visualization techniques—are used by the organization to strengthen risk prevention, detection, and mitigation.

Source: 2019 Governance Outlook: Projections On Emerging Board Matters, NACD, January 2019

|

Again, what isn’t stated, at least not clearly, is that a simple way to meet these expectations would be to ask the company’s CAE and/or the CRO and/or an outside risk management expert for his/her opinion on how the company is doing meeting these expectations.

Reason Number 2: Directors don’t know how to determine whether a company does, or does not, have an effective enterprise risk management (ERM) framework

At this point in this post I have already listed three similar but different sets of “authoritative” risk management effectiveness assessment criteria. Since the 2008 financial crisis, a lot of proposals focused on attributes of an effective risk management framework with differing views have emerged. One of the better ones, albeit with a financial sector bias, was issued by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in November 2013 titled “Principles for An Effective Risk Appetite Framework”. This guidance was sent to national financial regulators and securities regulators around the world, but otherwise received limited exposure, certainly very limited exposure with directors. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) issued new ERM guidance in 2017. International Organization for Standardization (ISO) updated ISO 3100, their risk management standard, in 2018. Both COSO and ISO list risk management effectiveness criteria.

Unfortunately, what isn’t at all clear is whether the FSB, national financial and securities regulators, the IIA, risk associations, ISO, or COSO have really determined the root problem with risk management frameworks in place in the world today. That problem, using terminology from the popular, but seriously flawed, “three lines of defense” framework the IIA originated many years ago and, unfortunately, many national regulators appear to like, is that management, the “first line,” is not responsible for, or expected to, formally assess and report on the status of risk linked to top objectives. As a result, management is not expected to learn how to formally and reliably assess and report on the status of risk linked to top objectives in most companies.

If a group or person is responsible for managing risk to important objectives but unable to assess the acceptability of residual risk linked to those objectives, it appears to be highly questionable they are well equipped to optimally manage those risks.

Today the majority of formal risk assessment and reporting done today is done by what are termed the second line (risk groups and other specialists) and the third lines (internal audit); not the people with primary responsibility for managing risks to key objectives, the first line.

Given virtually all of the companies at the heart of the Global Financial Crisis had internal audit and multiple risk groups using traditional risk and internal audit methods and doing the majority of formal risk assessments, one has to question whether regulators and standard setters really understand the root problem. For more details on flaws in regulatory direction linked to risk oversight see my 2012 report.

Reason Number 3: Boards don’t believe that Chief Audit Executives are qualified/independent enough to give an opinion

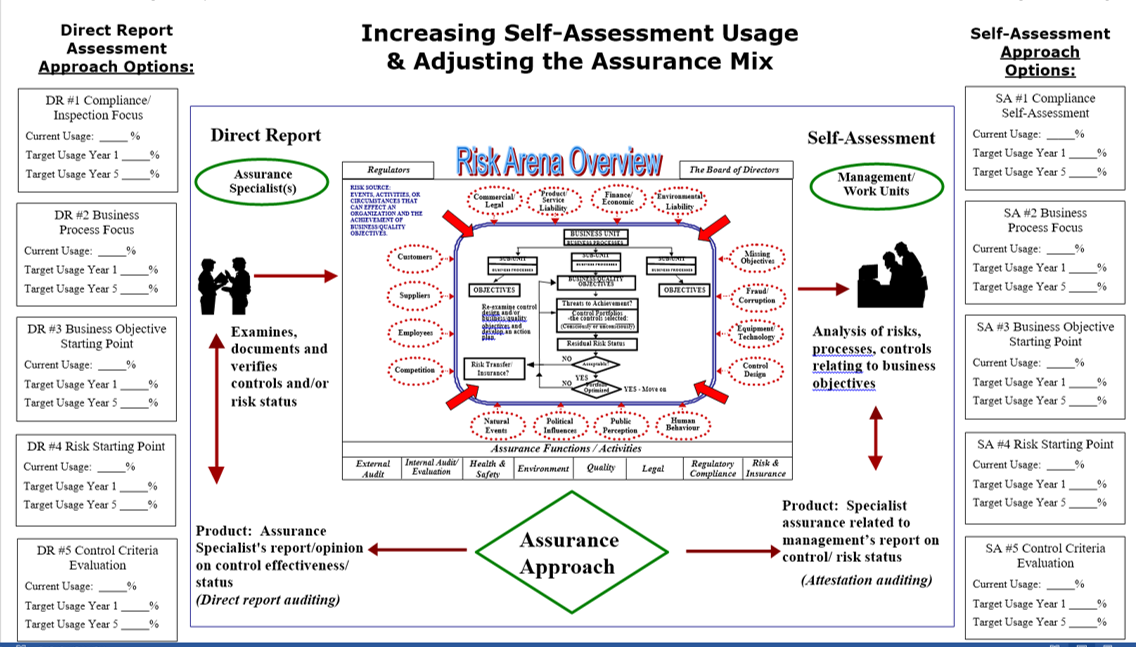

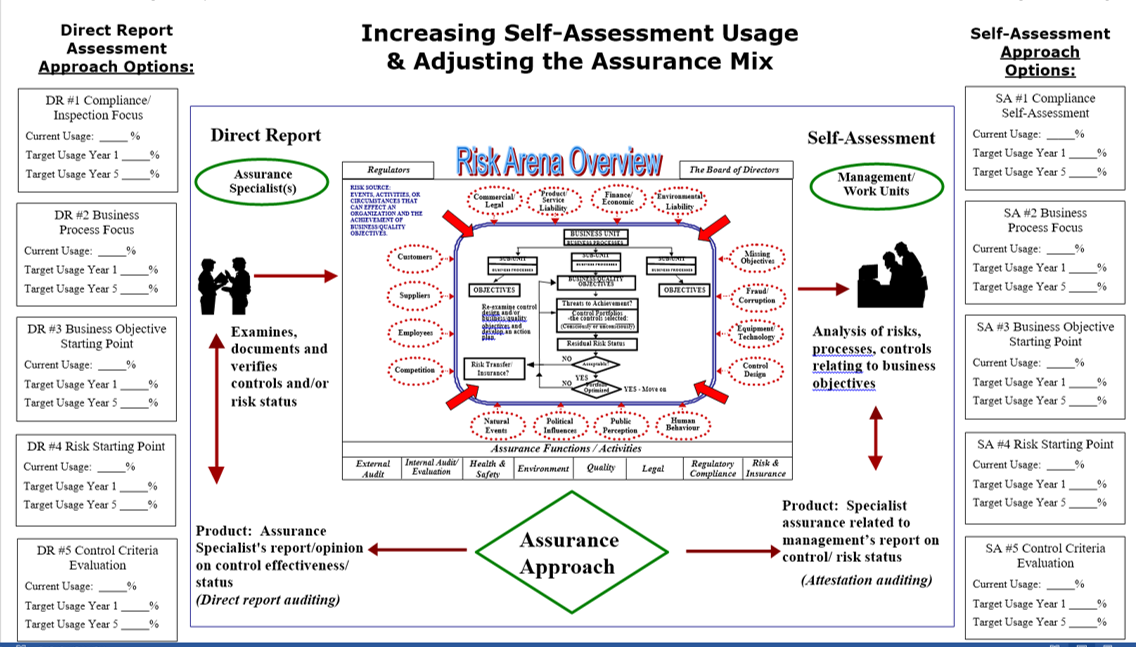

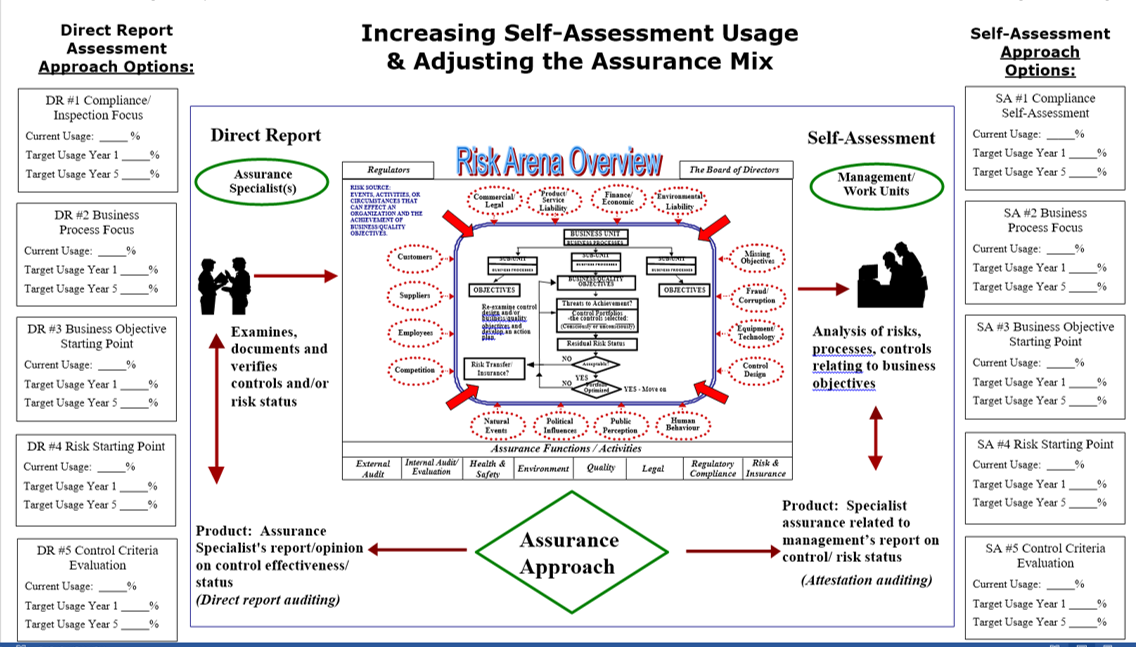

To provide more context an overview of the ten primary assurance methods in use today is shown below. More details on the 10 main assurance methods are available here.

In a large percentage of companies, the internal audit department uses some combination of the methods labeled “Direct Report” options shown on the left side of the diagram. Very few internal audit functions use the “Business Objectives Starting Point” method. Many use some combination of “Compliance/Inspection,” “Business Process,” “Risk Starting Point” or “Control Criteria Evaluation.” Risk groups generally use “Risk Starting Point” methods done by risk specialists from the left or working with management on the right. What this means is the vast majority of internal audit and specialist risk work done today does not follow the COSO ERM 2017 recommended sequence for completing risk assessments. That process starts by identifying corporate strategy and objectives, identifying risks to strategy and objectives, identifying risk responses to those risks, and then evaluating the acceptability of the residual risk status linked to specific objectives. It is “objective centric.”

Unfortunately, only a small percentage of companies, risk functions, or internal audit departments have evolved to objective centric risk assessment methods. A key question has to be:

If internal audit is incapable/unwilling to do its work using the most modern risk assessment methods, are they really equipped to give an opinion on the effectiveness of their company’s risk management framework, a framework that should be objective centric and owned and operated by management?

Another strong argument can be made that traditional internal auditing that reports on internal control effectiveness is, in fact, out of sync with modern risk management and risk terminology and is, in fact, a core part of many companies’ risk management frameworks. This would suggest that internal audit in many companies today are using outdated methods, are not independent, and should not be asked by boards for an opinion on risk management effectiveness.

Reason Number 4: Boards have been led to believe by major consulting firms, the IIA, CROs, regulators, and others that effective ERM means creating and maintaining a “risk register” as a foundation. This simply isn’t true.

COSO ERM 2004 – one of the first authoritative ERM guidance documents – unfortunately caused many people to believe that ERM is about creating and maintaining a risk register as the foundation for a framework. Consultants seized on this and promoted that idea to clients around the world. When COSO updated its 2004 ERM framework in 2017 it put a lot more emphasis on the need to start with strategy and objectives. Unfortunately, rather than clearly stating ERM should start by deciding which strategies and objectives are important enough to warrant formal risk analysis and then identifying risks that could create uncertainty that key objectives will be achieved, they were unwilling to take a position whether ERM should be objective centric or risk centric. The strongest statement in the COSO ERM 2017 Executive Summary on the many serious negatives of using a risk register as a foundation for ERM reads:

“Enterprise risk is more than a risk listing. It requires more than taking an inventory of all the risks in the organization. It is broader and includes practices management puts in place to actively manage the risks.”

Compounding the problem, the state of North Carolina and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants have conducted an annual survey on risk oversight practices for the past 10 years. Even a cursory read of those “authoritative” surveys quickly communicates the survey authors’ view is that the risk registers are the foundation for ERM.

More details on the differences between risk-centric and objective-centric ERM and the business case for change are available here.

The Way Forward

Directors all over the world need to be asking: Does the company have an effective risk management framework? If not, why not?

This would immediately require senior management disclose to the board, if they haven’t already, what risk management framework “effectiveness” criteria have they been using/aspiring to if any; and agreeing the risk management effectiveness criteria and measurement metrics that will be used with the board.

The next obvious question is: Given the board needs reliable information on the current effectiveness of the company’s risk management framework, who should/will provide the board with the information?

The answer to the second question isn’t simple. The flawed three lines of defense framework mentioned earlier says the second line, the risk function, should be reporting on the effectiveness of the first line/management’s risk management framework. The third line, internal audit, should be reporting on the effectiveness of the first line and the second line. For reasons stated above, and other reasons too long to cover here, this hasn’t been happening in a lot of companies. Boards need to ask why.

Directors that are unable to demonstrate they are monitoring the effectiveness of risk management frameworks in the companies they oversee may themselves be assuming significant personal risk. Boards asking management the questions above is increasingly seen by regulators and the courts as an important element of effective board risk oversight. It’s time to ask some tough questions.

The views presented on the ESG Blog are not the official views of The Conference Board or the ESG Center and are not necessarily endorsed by all members, sponsors, advisors, contributors, staff members, others associated with The Conference Board or the ESG Center.

On Governance is a series of guest blog posts from corporate governance thought leaders. The series, which is curated by the ESG Center research team, is meant to serve to spark discussion on some of the most important corporate governance issues.

Directors should be asking for information on the effectiveness of risk management processes. Good practice risk oversight due diligence guidance clearly says they should. Evidence suggests many boards have not been. Why not?

In 2000, after another perfect storm of colossal corporate governance breakdowns, the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) changed the international professional practice standards and said internal auditors should report to boards on the effectiveness of risk management processes. Evidence suggests a large percentage of auditors ignored the new IIA “should-do” standard. In 2010, following the Global Financial Crisis, IIA Global changed the words in the standard from “should” to “must” assess effectiveness of risk management and provided the following interpretation.

Determining whether risk management processes are effective is a judgment resulting from the internal auditor’s assessment that:

- Organizational objectives support and align with the organization’s mission.

- Significant risks are identified and assessed.

- Appropriate risk responses are selected that align risks with the organization’s risk appetite.

- Relevant risk information is captured and communicated in a timely manner across the organization, enabling staff, management, and the board to carry out their responsibilities.

Evidence suggests that since this IIA standard was first enacted almost 20 years ago, a large percentage of Chief Audit Executives (CAEs) have not provided clear opinions to their boards on the effectiveness of their company’s risk management processes. Recognizing the magnitude of this problem, IIA Global has just released new “supplemental” guidance in the hope that more IIA members around the world will comply. (see this site for details)

Given most CAEs are rational and educated people that usually work particularly hard to respond to requests from CEOs and audit committees, it would seem that the number one reason internal auditors haven’t been providing opinions on risk management frameworks is simply that boards of directors haven’t asked for one. An obvious question is “Why not?”

Reason Number 1: Most authoritative guides don’t say boards should ask the company’s Chief Internal Auditor for an opinion on the effectiveness of risk management processes

In 2009, just after the Global Financial Crisis, the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) released some very good guidance for directors via one of their “Blue Ribbon Commissions” reports. It was the best guidance I had seen at the time:

|

While risk oversight objectives may vary from company to company, every board should be certain that:

- The risk appetite implicit in the company’s business model, strategy, and execution is appropriate.

- The expected risks are commensurate with the expected rewards.

- Management has implemented a system to manage, monitor, and mitigate risk, and that system is appropriate given the company’s business model and strategy.

- The risk management system informs the board of the major risks facing the company.

- An appropriate culture of risk-awareness exists throughout the organization.

- There is recognition that management of risk is essential to the successful execution of the company’s strategy.

Source: Report Of The NACD Blue Ribbon Commission, Risk Governance: Balancing Risk And Reward, October 2009

|

What isn’t stated, at least not clearly, is that a simple way to meet these expectations would be to ask the company’s Chief Audit Executive and/or the Chief Risk Officer and/or an outside independent risk management expert for an opinion each year on how the company is doing on each of these NACD risk management “effectiveness” criteria.

In January of this year, 10 years after the NACD issued the guidance above, the NACD released more guidance for directors on how to oversee risk management frameworks. The risk management “effectiveness” criteria have shifted and now put more emphasis on “embedding” risk management in the lines of business and core processes and differentiating “disruptive risks” from “day-to-day risks”:

|

Given the pace of change experienced in the industry and the nature and relative riskiness of the organization’s operations, does the board understand the quality of the ERM process informing its risk oversight? How actionable is management’s risk information for decision making? Does ERM effectively capture and assess early warning signals that indicate more unusual or disruptive risks on the horizon? These and other questions focus on the robustness and maturity of the risk-management process. Directors should ensure that the critical attributes of risk-oversight excellence are present:

- Critical and potentially disruptive enterprise risks are differentiated from the day-to-day risks of managing the business so as to focus the dialogue on the risks that matter to the C-suite and the board.

- Accountability is established for both traditional and disruptive risks and clearly embedded in the lines of business and core processes.

- Actionable new risk information is not only reported up but also widely shared to enable more informed decision making.

- An open, positive dialogue for identifying and evaluating opportunities and risks is encouraged. Consideration should be given to reducing the risk of undue bias and groupthink so that adequate attention is paid to differences in viewpoints that may exist among different executives.

- Advancements in the application of new technologies—including AI, machine learning, mobile technologies, advanced data analytics, and visualization techniques—are used by the organization to strengthen risk prevention, detection, and mitigation.

Source: 2019 Governance Outlook: Projections On Emerging Board Matters, NACD, January 2019

|

Again, what isn’t stated, at least not clearly, is that a simple way to meet these expectations would be to ask the company’s CAE and/or the CRO and/or an outside risk management expert for his/her opinion on how the company is doing meeting these expectations.

Reason Number 2: Directors don’t know how to determine whether a company does, or does not, have an effective enterprise risk management (ERM) framework

At this point in this post I have already listed three similar but different sets of “authoritative” risk management effectiveness assessment criteria. Since the 2008 financial crisis, a lot of proposals focused on attributes of an effective risk management framework with differing views have emerged. One of the better ones, albeit with a financial sector bias, was issued by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in November 2013 titled “Principles for An Effective Risk Appetite Framework”. This guidance was sent to national financial regulators and securities regulators around the world, but otherwise received limited exposure, certainly very limited exposure with directors. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) issued new ERM guidance in 2017. International Organization for Standardization (ISO) updated ISO 3100, their risk management standard, in 2018. Both COSO and ISO list risk management effectiveness criteria.

Unfortunately, what isn’t at all clear is whether the FSB, national financial and securities regulators, the IIA, risk associations, ISO, or COSO have really determined the root problem with risk management frameworks in place in the world today. That problem, using terminology from the popular, but seriously flawed, “three lines of defense” framework the IIA originated many years ago and, unfortunately, many national regulators appear to like, is that management, the “first line,” is not responsible for, or expected to, formally assess and report on the status of risk linked to top objectives. As a result, management is not expected to learn how to formally and reliably assess and report on the status of risk linked to top objectives in most companies.

If a group or person is responsible for managing risk to important objectives but unable to assess the acceptability of residual risk linked to those objectives, it appears to be highly questionable they are well equipped to optimally manage those risks.

Today the majority of formal risk assessment and reporting done today is done by what are termed the second line (risk groups and other specialists) and the third lines (internal audit); not the people with primary responsibility for managing risks to key objectives, the first line.

Given virtually all of the companies at the heart of the Global Financial Crisis had internal audit and multiple risk groups using traditional risk and internal audit methods and doing the majority of formal risk assessments, one has to question whether regulators and standard setters really understand the root problem. For more details on flaws in regulatory direction linked to risk oversight see my 2012 report.

Reason Number 3: Boards don’t believe that Chief Audit Executives are qualified/independent enough to give an opinion

To provide more context an overview of the ten primary assurance methods in use today is shown below. More details on the 10 main assurance methods are available here.

In a large percentage of companies, the internal audit department uses some combination of the methods labeled “Direct Report” options shown on the left side of the diagram. Very few internal audit functions use the “Business Objectives Starting Point” method. Many use some combination of “Compliance/Inspection,” “Business Process,” “Risk Starting Point” or “Control Criteria Evaluation.” Risk groups generally use “Risk Starting Point” methods done by risk specialists from the left or working with management on the right. What this means is the vast majority of internal audit and specialist risk work done today does not follow the COSO ERM 2017 recommended sequence for completing risk assessments. That process starts by identifying corporate strategy and objectives, identifying risks to strategy and objectives, identifying risk responses to those risks, and then evaluating the acceptability of the residual risk status linked to specific objectives. It is “objective centric.”

Unfortunately, only a small percentage of companies, risk functions, or internal audit departments have evolved to objective centric risk assessment methods. A key question has to be:

If internal audit is incapable/unwilling to do its work using the most modern risk assessment methods, are they really equipped to give an opinion on the effectiveness of their company’s risk management framework, a framework that should be objective centric and owned and operated by management?

Another strong argument can be made that traditional internal auditing that reports on internal control effectiveness is, in fact, out of sync with modern risk management and risk terminology and is, in fact, a core part of many companies’ risk management frameworks. This would suggest that internal audit in many companies today are using outdated methods, are not independent, and should not be asked by boards for an opinion on risk management effectiveness.

Reason Number 4: Boards have been led to believe by major consulting firms, the IIA, CROs, regulators, and others that effective ERM means creating and maintaining a “risk register” as a foundation. This simply isn’t true.

COSO ERM 2004 – one of the first authoritative ERM guidance documents – unfortunately caused many people to believe that ERM is about creating and maintaining a risk register as the foundation for a framework. Consultants seized on this and promoted that idea to clients around the world. When COSO updated its 2004 ERM framework in 2017 it put a lot more emphasis on the need to start with strategy and objectives. Unfortunately, rather than clearly stating ERM should start by deciding which strategies and objectives are important enough to warrant formal risk analysis and then identifying risks that could create uncertainty that key objectives will be achieved, they were unwilling to take a position whether ERM should be objective centric or risk centric. The strongest statement in the COSO ERM 2017 Executive Summary on the many serious negatives of using a risk register as a foundation for ERM reads:

“Enterprise risk is more than a risk listing. It requires more than taking an inventory of all the risks in the organization. It is broader and includes practices management puts in place to actively manage the risks.”

Compounding the problem, the state of North Carolina and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants have conducted an annual survey on risk oversight practices for the past 10 years. Even a cursory read of those “authoritative” surveys quickly communicates the survey authors’ view is that the risk registers are the foundation for ERM.

More details on the differences between risk-centric and objective-centric ERM and the business case for change are available here.

The Way Forward

Directors all over the world need to be asking: Does the company have an effective risk management framework? If not, why not?

This would immediately require senior management disclose to the board, if they haven’t already, what risk management framework “effectiveness” criteria have they been using/aspiring to if any; and agreeing the risk management effectiveness criteria and measurement metrics that will be used with the board.

The next obvious question is: Given the board needs reliable information on the current effectiveness of the company’s risk management framework, who should/will provide the board with the information?

The answer to the second question isn’t simple. The flawed three lines of defense framework mentioned earlier says the second line, the risk function, should be reporting on the effectiveness of the first line/management’s risk management framework. The third line, internal audit, should be reporting on the effectiveness of the first line and the second line. For reasons stated above, and other reasons too long to cover here, this hasn’t been happening in a lot of companies. Boards need to ask why.

Directors that are unable to demonstrate they are monitoring the effectiveness of risk management frameworks in the companies they oversee may themselves be assuming significant personal risk. Boards asking management the questions above is increasingly seen by regulators and the courts as an important element of effective board risk oversight. It’s time to ask some tough questions.

The views presented on the ESG Blog are not the official views of The Conference Board or the ESG Center and are not necessarily endorsed by all members, sponsors, advisors, contributors, staff members, others associated with The Conference Board or the ESG Center.

0 Comment Comment Policy