-

Email

Linkedin

Facebook

Twitter

Copy Link

Loading...

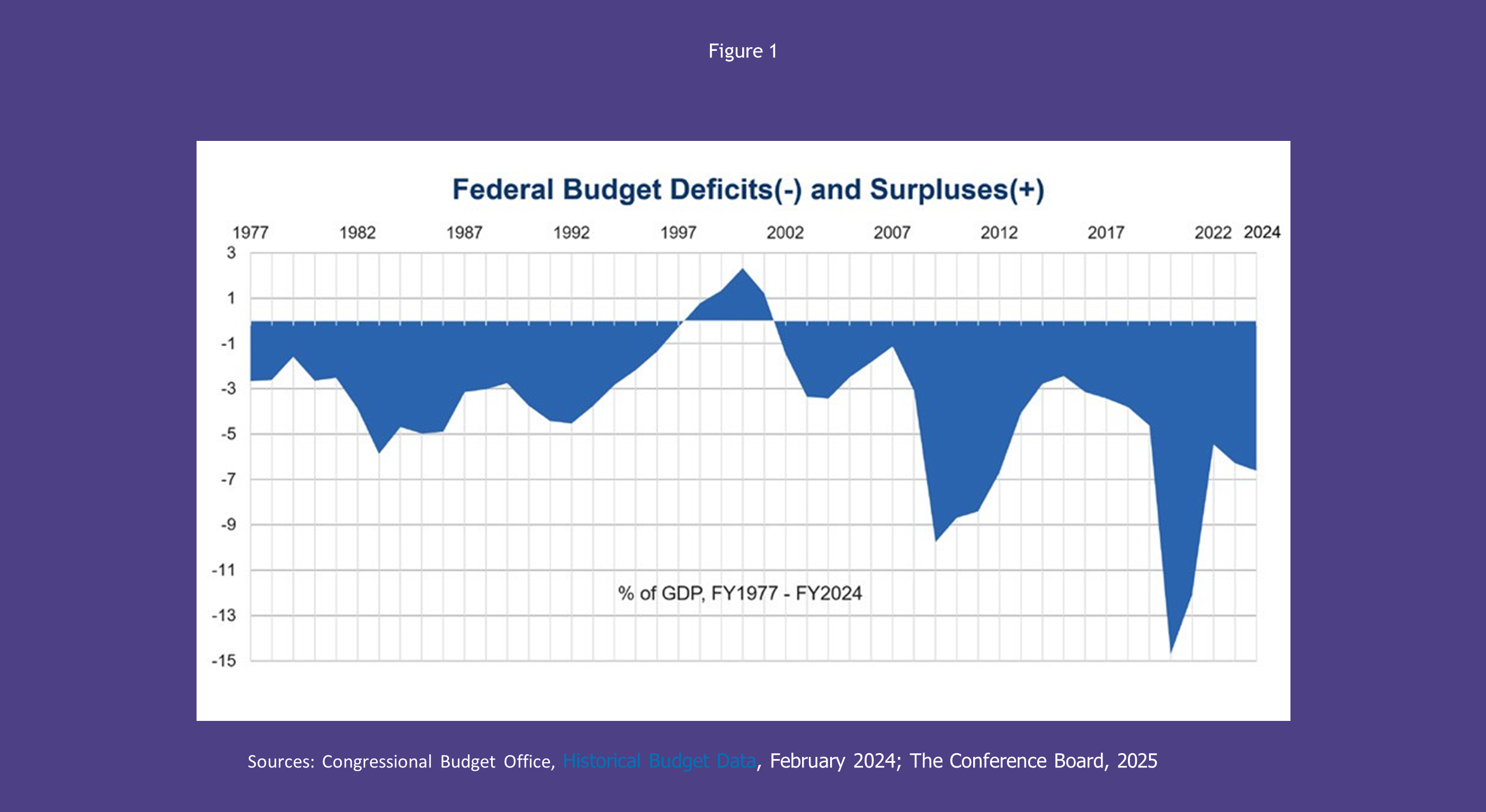

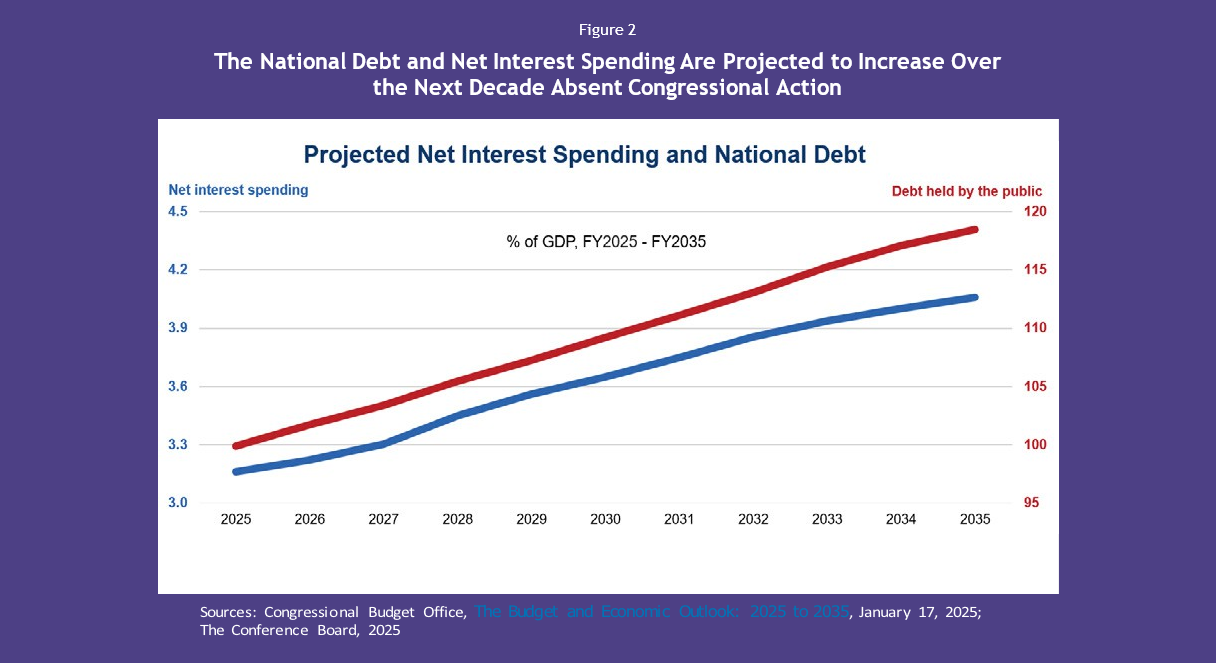

While Congress is responsible for setting the Federal budget through the annual appropriations process, in recent decades it has too often failed to fulfill its duties in a timely and orderly manner, with late and incomplete budgets leading to omnibus bills, continuing resolutions (CRs), and regularly recurring threats of government shutdown. Of course, Congress is also responsible for setting its own rules of procedure—and this provides a significant opportunity to change course. Urgent reform is needed to rebuild a predictable and fair annual budget process that permits Congress to debate fully the important issues at stake in each budget and restore confidence in our fiscal policy for the American people, businesses, and the government itself. The following recommendations are ideally intended to be part of a comprehensive reform package. Congress may consider these options either through reforms to rules, via legislation, or through a bipartisan Congressional committee on fiscal responsibility to facilitate reform. Before the 1970s, Congressional action on the Federal budget lacked formal coordi- nation, with the President taking the lead through the preparation of a Presidential budget request under what is now the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The Defense Department, then under Robert McNamara, implemented the Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System as a management tool to analyze and operationalize budgetary decisions by outlining a program structure, quantitative metrics of inputs and outputs, the information system required to collect these data, a decision- making process, and an evaluation of outcomes. President Lyndon B. Johnson expanded this system to the entire Federal government by Executive Order in 1965. In the early 1970s, President Richard Nixon defied Congress by refusing to fully spend appropriated funds for social programs. As lawmakers challenged the President’s actions in court, President Nixon argued that Congress did not have a formal budget process to aggregate spending and revenue policies and relating total spending to total revenue, meaning that Presidential decisions to “impound” funding were necessary to restrain total spending and deficits. In response, Congress passed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (the “Act”) to limit the President’s ability to impound funding and establish the current Federal budget process. The Supreme Court agreed with Congress’ view in a case on funds withheld in 1972 in Train v. City of New York (1975). As noted above, the Act established a formal process to develop, coordinate, and enforce budgetary priorities. The Act specifies the process of developing a concurrent resolution to guide Congress. Title X of the law (known as the “Impoundment Control Act”) constrains Presidential authority to spend less than Congress appropriates. The Impoundment Control Act classifies impoundment into two distinct categories: a “deferral” that delays the use of funds and a “recission” (a request to Congress to cancel an appropriation or other form of budget authority). The Impoundment Control Act specifies the process for the President to request a rescission of funds or withhold appropriated funds from obligation. The President must submit a special message explaining the amounts to be rescinded, the estimated fiscal and program effects, and the reasons for rescission. Funds may be withheld for 45 days as Congress considers the request. Under expedited procedures to facilitate review of the request that limit committee consideration and restrict floor debate, Congress may pass a bill that includes all or part of the requested rescission. If Congress has not completed action on the request within 45 days, the President must release the funds. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) oversees the Executive Branch’s compliance with the Act. The President may request rescissions outside of this process, but funds may not be withheld while Congress reviews these separate requests. Congress may also rescind funds on its own under the standard legislative process. Rising deficits in the late 1970s and early 1980s prompted Presidential action and Congress to pass legislation to enforce budgetary outcomes to reduce the budget deficit, limit spending, or prevent deficit increases. President Carter established zero- based budgeting during his Administration, calling for the full reevaluation of the budgets of each Federal agency instead of simply proposing cuts or increases from current base funding. The Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 established a statutory requirement for gradual reduction of deficits over six years by setting annual deficit limits. The President could enforce these deficit limits through “sequestration” orders cancelling spending if legislation did not stick to the statutory targets. Once sequestration is triggered, spending reductions are automatic. The Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 focused on preventing future legislation from undoing the savings achieved. This law implemented “pay-as-you-go” (PAYGO) procedures to limit increases in the deficit due to new direct spending or revenue adjustments and instituted statutory caps on discretionary spending. These procedures were initially in effect for five years, though Congress extended them twice in subsequent legislation to apply until 2002. In the 2010s, Congress passed the Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010 that reinstated PAYGO. The Budget Control Act of 2011 reestablished statutory limits on discretionary spending, split into defense and nondefense limits, for fiscal years (FY) 2012 through 2021. Subsequent legislation modified the spending limits and enforcement procedures of the Budget Control Act until the expiration of the original law at the end of FY2021. More recently, the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 established discretionary spending caps for FY2024 and FY2025 and provided an incentive to avoid continuing resolutions through the threat of sequestration in exchange for a suspension in the debt limit. Recent debate on the President’s ability to reduce or pause Federal funding appropriated by Congress and the operations of the US DOGE Service (also known as the “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE)) demonstrates the salience of issues involving the Federal budget process and the roles of each stakeholder in the process. Despite the formal process in the established Act and subsequent legislation that established other budgetary control procedures, Congress has failed to pass the Federal budget in a timely and orderly manner, particularly in the past several decades. The concurrent budget resolution has not been passed by the April 15 target date in 30 of the past 49 fiscal years, excluding FY2025. In nine of the past 15 years, the House and Senate have used deeming resolutions or other ad hoc legislation to guide the overall Federal budget process. Congress has only passed all appropriations bills on time four times since FY1977. Since FY1997, Congress has never passed more than five of the 12 appro- priations bills on time. The situation has deteriorated since FY2010, as Congress failed to pass all 12 appropriations bills by October 1 in all but two fiscal years. These challenges to regular order in the budget process have led to the increased use of omnibus legislation, continuing resolutions (CRs), and threats of a government shutdown. Omnibus bills have been used to pass all or nearly all the Federal budget since FY2007, except for two fiscal years. CRs are becoming standard practice in Congress: between FY1998 and FY2023, Congress has taken an average of 113 days past the October 1 start of a fiscal year to enact that fiscal year’s final appropriations bill. The final appropriations bill for FY2017 did not become law until May 2017, more than seven months after the start of the fiscal year. Because of the increased need for CRs, the threat of a government shutdown has been ever-present, highlighting the dysfunctional process. Excluding a technical shutdown in 2018, there have been five government shutdowns since 1995, with the longest one in 2018-19 lasting 35 days. Government shutdowns require “nones- sential” functions to shut down, cause furloughs, and delay pay for Federal government workers, impacting US businesses and the broader economy. All the while, the Federal government has run an annual deficit in every fiscal year since FY2002, with the total Federal debt held by the public projected to reach 100% of GDP in FY2025. The Federal budget has four major components: mandatory spending, discretionary spending, net interest spending, and revenues. The current process concerns only discre- tionary spending, which is subject to annual appropriations set by Congress. (Revenues are considered separately because legislation on taxes and tariffs falls under the juris- diction of the House Committee on Ways and Means and the Senate Finance Committee, and the Origination Clause of the Constitution requires that all revenue measures originate in the House.) The 12 appropriations bills fund many government programs for major US national priorities, including national defense, infrastructure, transportation, education, housing, and social service programs. Crucially, discretionary spending accounts for less than one-third of total Federal government spending—the rest is tied to mandatory spending based on statutory formulas, principally for Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Spending for interest on the national debt accounts for 13% of total Federal outlays, but is a form of mandatory spending outside the budget process. Congress and the President work together to develop and enact the Federal budget, and Federal agencies are charged with implementing it under the “Take Care” clause of the Constitution requiring “that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Federal agencies submit budget requests to OMB, which then develops the President’s budget proposal along with estimates of revenues and an economic forecast. By the first Monday in February before the start of a fiscal year, the President submits a budget proposal to Congress (with different procedures for years in which a new President is inaugurated). Following this, the appropriations process begins; after Congress completes the appropriations process, the President signs or vetoes the appropriations bills. In Congress, two sets of committees play a crucial role in the overall process. The Budget Committees in the House and Senate guide overall spending levels, develop the budget resolution, and provide oversight of the Federal budget and the budget development process. The Appropriations Committees in the House and the Senate are responsible for crafting and passing the 12 appropriations bills that fund Federal discretionary spending. Each Appropriations Committee has 12 subcommittees that align with each appropriations bill (e.g., defense, homeland security, agriculture, energy and water devel- opment, transportation and housing and urban development, etc.). Finally, CBO provides independent analyses of spending and revenue proposals, as well as long-term fiscal, economic, and demographic forecasts to guide lawmakers. Once the President submits a proposed budget, each Budget Committee works to draft and agree to a budget resolution according to the parameters in Section 301 of the Act. The authorization committees in Congress hold hearings on the Administration’s budget requests. No later than six weeks after the President’s budget submission, each autho- rization committee submits its views and estimates of spending and revenues within its respective jurisdiction to the Budget Committees, which then use the information from the committees, hearings, CBO, and other sources to craft it. The budget resolution includes aggregates across four aspects of the Federal budget: total revenues, total new budget authority and outlays, the surplus or deficit, and public debt. By law, the budget resolution excludes the revenues and spending from the Social Security Trust Funds. The budget resolution itself is a simple document and is required to have a minimum timeframe of five years, though Congress often sets budget aggregates for the next 10 years. It sets ceilings across 19 categories of government expenditures and a revenue floor for what the Federal government will collect in taxes. The difference between these two aggregate numbers is the expected surplus or deficit, which has a direct impact on the public debt totals and the debt limit. Once the House and Senate Budget Committees have passed a budget resolution, each resolution is considered on the floor of each chamber with the option for amendments, though debate is limited and the measure only requires majority support in the Senate to pass. If both the House and the Senate agree to an identical budget resolution, it is known as a “concurrent resolution,” which does not have to go for the President’s signature. Federal law requires the passage of a budget resolution by April 15 and prohibits consideration of budgetary legislation prior to the adoption of a budget resolution. This legislation is important to set an enforceable upper limit on overall budget appropriations and to bring accountability to the process. Under a concurrent resolution, Members of Congress can hold the legislative body accountable for sticking to its budgetary targets and framework through “point of order” challenges. In the House, these point of order challenges can be waived by a rule from the House Rules Committee setting the conditions under which each appropriations bill will be considered on the House floor, which only requires a simple majority to pass. In the Senate, these point of order challenges are more potent as the filibuster rule applies, requiring 60 votes to waive the point of order. If the House and Senate cannot agree on a concurrent resolution, each chamber may adopt ad hoc legislation to guide the budget process, known as “deeming resolutions.” They, or other budget related legislation, such as the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, are crucial to set the overall framework for the budget process. After passage of the budget resolution, the House and Senate Appropriations Committees assume control of the process. The budget resolution contains a “302(a) allocation” specifying the spending total that each Appropriations Committee will allocate. This total allocation is then subdivided into separate “302(b) allocations” for each subcommittee of the Appropriations Committee. If, however, Congress does not agree to a concurrent resolution or other type of budget resolution by April 15, the House is permitted to consider regular appropriations bills after May 15. By custom, in the normal process, appropriations bills originate in the House, with the Senate considering them afterwards and any differences hashed out in a conference committee before final passage. In recent years, the Senate has run a parallel process and crafted its own bills given delays in the House originating budget legislation. Over the past few decades, Congress has combined two or more of the 12 appropriations bills into a “minibus” or “omnibus” to expedite passage of the Federal budget, often after delays and missed deadlines. All 12 appropriations bills must be enacted into law by the start of the fiscal year on October 1 to avoid a full or partial government shutdown. To prevent this deleterious outcome, Congress can pass and the President can sign a CR to provide interim budget authority. This stopgap funding may last for any duration that Congress decides, and it is often generally based on a rate of operations funded in the previous year as opposed to a specific amount of funding, although CRs have also included direct funding for certain priorities, such as disaster relief. CRs have become more common as Congress has failed to complete the budget process in a timely and orderly manner. The Federal budget process has a few additional features of note. The first is the option of budget “reconciliation” tied to the budget resolution. Reconciliation is an expedited process to consider legislation on taxation, mandatory spending, and other budget components to meet the revenue and spending targets outlined in a budget resolution. Under reconciliation, the House and the Senate must adopt a concurrent resolution with special instructions to Congressional committees to develop and report legislation related to spending, revenues, and/or the debt limit within the remit of the respective committees. The reconciliation process has unique procedures that allow for packaging legislation from multiple committees into omnibus bills, limited amendment opportunities, and limits on the duration of debate on the Senate floor. As such, legislation that meets the budgetary targets in the budget resolution can pass with a simple majority vote in the Senate. To hold lawmakers accountable during reconciliation, the Senate adopted the “Byrd Rule” (named after the late West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd) to prohibit extraneous provisions in the measure or offering them as amendments, specifically nonbudgetary provisions or provisions that are contrary to the purposes described in the budget resolution or not germane. Changes to authorizing legislation without any fiscal impact, changes to Social Security, or provisions that are not fully offset (either through spending cuts or revenue increases) beyond the budgetary window under consideration are not allowed. These procedural advantages have led to its increased use to pass major legislation in the past two decades, notably the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. The “debt limit” (or “debt ceiling”) is another important component of the budget process. The debt limit restricts the amount of outstanding debt the Federal government can hold—once the debt limit is reached, the Treasury Department loses its legal authority to issue debt to raise cash. This inhibits the Federal government’s ability to pay for ongoing obligations associated with running the government and financing existing obligations that have accrued in the form of sovereign debt. A fixed debt limit is unique to the US and Denmark. While some have proposed removing the debt limit (which would require amending the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917), lawmakers have used the debt limit as a negotiating tool for fiscal policy. Reconciliation instructions can address the debt limit, either by increasing it, suspending it, or eliminating it entirely. The Treasury Department also risks defaulting on its obligations if the debt limit is not increased or suspended to align with the deficits in the Federal budget, which would have severe financial and economic impacts that threaten the US and global economy, the credit rating for US Treasury securities, and the role of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Finally, Congress can pass “supplemental appropriations” to enhance funding for Federal agencies during the current fiscal year in response to natural disasters, unexpected contingencies, and geopolitical events. Supplemental appropriations provide additional budget authority in the current fiscal year if existing appropriations are insufficient or to finance activities not provided for in the regular appropriations process. Recent examples of supplemental appropriations legislation in 2024 include Federal disaster relief funding after Hurricanes Helene and Milton and a package of supplemental funding addressing US national security priorities in Ukraine, Israel, and the Indo-Pacific region. Congress’s underwhelming record with completing the Federal budget process raises the urgent need for reform to restore regular order and improve governance of US fiscal policy. Increasing deficits and an unsustainable national debt are the consequences of a broken budget process. Of particular concern is the cost of servicing the national debt: CBO projects net interest outlays to increase from $952 billion in FY2025—higher than defense spending this year—to $1.8 trillion by FY2035, equivalent to 4.1% of GDP and more than projected Medicare outlays that year. Without reform, the national debt and net interest spending will continue to increase, crowding out other national priorities and potentially causing a loss of confidence in the Federal government’s ability to repay the debt. This will have adverse impacts on the economy, particularly on the Federal government’s credit rating, the higher interest rates that the US Treasury must pay investors to compensate for the greater risk of default, and the value of the US dollar as investors seek safer investments. Congress should consider reforms that align with the following principles: In recent years, Congressional leadership in the House has stated its goal to stick to regular order outlined in the Act and consider all 12 appropriations bills separately instead of relying on omnibus bills and CRs to complete the budget process. Nevertheless, the process for FY2024 and FY2025 has continued to be replete with delays and last-minute deals to keep the government open and finalize the budget past the start of the fiscal year. This outcome, despite the efforts of House leadership, demonstrates how broken the process has become and the pressing need for improvements. Even under a better-designed budget process, CRs and supplemental appropriations will likely be needed given the geopolitical risks and increasingly expensive natural disasters that the US faces. While CRs do generally function as a restraint on spending by keeping funding levels flat for many existing Federal programs, CRs are employed too often as a crutch to cover for a broken process. Their use also dissuades the comprehensive review of all programs through hearings, amendments, and debate on the floor of the House and Senate. Thus, CRs should be a last resort, and supplemental appropriations should be solely used to address unanticipated natural disasters, truly unexpected events, and national security and defense activities. The following options for reform are grouped into three broad categories that align with the framework and principles for a functioning Federal budget process. These categories seek to improve the timeliness of the process, mitigate dysfunction and challenges to regular order, and incorporate long-term planning into the process. A comprehensive reform package from this menu of options will increase the chances of success, which could be facilitated by a bipartisan Congressional commission on fiscal responsibility. One option to improve the timeliness of the process is to require lawmakers to pass a Federal budget on time by prohibiting legislation with any fiscal effect from being considered until a budget is passed. Congressional leadership could also forbid Members of Congress to leave for scheduled recesses if a budget resolution is overdue. These requirements could be waived during genuine emergencies or in the face of unantici- pated events but should remain the exception. These rules could have associated financial penalties for Members of Congress, such as withheld pay and reimbursement. On the state level, California regularly failed to pass budgets on time until the voters enacted Proposition 25 in 2010, which requires members of the state Legislature to permanently forfeit their pay and reimbursement for travel and living expenses for each day after June 15 (California’s statutory deadline) that a budget is not passed and sent to the Governor. Another, and more radical, idea is for Congress to move from an annual budget process to a biennial one covering two years. This longer cycle would allow lawmakers more time to comprehensively review all programs within their purview, focus on oversight and long-term policies, spend more time in their communities and interact with constituents after the budget process is completed, and provide greater certainty for agencies. Moving to a two-year cycle would also allow more time to debate important policy topics outside the budget process. The biennial cycle can encompass two-year budget resolutions, two-year appropriations, and/or multi-year authorizations of Federal programs. Proponents of this reform also suggest setting the biennial cycle to avoid budgets in election years, thus promoting bipartisan compromise. Congress has already organically set two-year topline funding levels several times in the past 15 years, namely in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2023. However, a biennial budget cycle may also have some drawbacks that suggest the need to pair this reform with others. Biennial budgets may increase the stakes for budgetary decisions in the years when the budget is developed and may decrease the frequency of oversight when compared to a well-functioning annual review of Federal programs. Supplemental appropriations and mid-cycle budgetary adjustments could become more common given the complex geopolitical and environmental context facing the US today. If given longer deadlines, Congress may also simply have more time to procrastinate, potentially leading to an increased use of CRs. As such, a biennial budget process is not by itself a comprehensive solution. Others have proposed more radical ideas. Taking a cue from the private sector, quarterly budget performance reviews based on measurable outcomes could provide Congress with updates on spending and allow lawmakers to hold agencies accountable during this two-year period. Congress could explore the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain technologies to automate budget tracking and provide transparency on the Federal government’s fiscal performance to the public. The recent deployment of the US DOGE Service (also known as the Department of Government Efficiency), may involve greater use of AI technologies to detect fraud. Greater transparency on the use of Federal funding (first promised in the Obama/Coburn Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act in 2006) helps Congress do its job, in particular providing useful background for annual reviews of appropriated funds. But the use of this technology, particularly regarding Federal payments to individuals, also involves serious issues of data privacy (including privacy rights granted by Federal statutes) which Congress should address. To mitigate the dysfunction with the current Federal budget process, Congress has several methods to strengthen budget enforcement mechanisms. Congress could truly enforce the PAYGO statutes it enacted to address unsustainable deficits and scale back exemptions from PAYGO rules. Congress may also limit increases in discretionary spending based on realistic trends, such as historical levels, to ensure follow-through and employ sequestration as a last resort if debt reduction targets are not reached. The budget resolution should guide the application of these budget enforcement mechanisms and set the deficit reduction targets necessary to align the Nation’s fiscal trajectory on a more positive path, with the ultimate goal of enforcing both the Act and PAYGO statutes. When Congress negotiates the Federal budget, lawmakers could employ a method to automatically increase revenues (similar to sequestration on the spending side) to include another tool for lawmakers to force the timely and orderly completion of the budget process. Because one Congress cannot bind a future Congress, any revenue increases would be limited to the two years of a Congress. This tool could motivate lawmakers who oppose tax increases to compromise and adhere to deadlines and would prompt the consideration of revenues in the budget process. Congress may also establish automatic continuing resolutions if it does not pass all 12 appropriations bills by the October 1 start of a fiscal year to avoid the threat of a government shutdown and associated costs to the economy. For these automatic CRs, Congress could choose to keep all existing funding for current programs flat to constrain the growth of discretionary spending or choose to increase funding by a measure of inflation to keep funding flat in real terms. Either way, automatic CRs would reduce the brinksmanship that has become so common in recent years. Congress could, of course, amend the automatic CR at any time it chose, but this process would avoid the risk of government shutdowns (absent reaching the debt ceiling). Another potential method to restore regular order, though one that poses risks of shifting checks and balances within the overall system, would be to increase the role of the President in the Federal budget process. Consistent with separation of powers in the Constitution, Congress will likely hesitate to cede more control to the Executive Branch as Congress holds the “power of the purse.” Nevertheless, the President must sign or veto the 12 appropriations bills and already has a crucial role in the process. More direct Presidential involvement in the process could be a last resort if Congress fails to adhere to its deadlines. If Congress follows the procedures laid out in the Act, then it should act alone in developing the budget until the final appropriations bills are sent to the President for signature, consistent with Congress’s exclusive powers on legislation. In this scenario, if Congress were to decide the President should be further involved as a last resort, the budget process could require concurrent budget resolutions to be joint resolutions approved by the President. While introducing an additional component to negotiations could reduce their efficiency, the House and Senate might have more of an incentive to compromise with each other to protect the interests of the Legislative Branch. Even after agreeing on a joint budget resolution, Congress and the President would still certainly debate budgetary policy and the specifics of legislation to implement the targets in the budget resolution. However, a budget resolution agreed between the President and Congress would at least set agreement on topline spending numbers for the fiscal year under consideration and target revenue and deficit figures. Another option is the line-item veto, which 44 states have in their own constitutions. A Presidential line-item veto would grant the President the ability to reduce specific appropriations passed by Congress before enactment of the 12 appropriations bills instead of a full veto of the legislation. In 1996, Congress enacted the Legislative Line Item Veto Act, permitting the President to cancel any amount of entitlement, cancel in whole any amount of increased appropriation, and to remove certain tax benefits, with the money being canceled going to reduce the deficit and the ability of Congress to disapprove the President’s veto. The Supreme Court ruled this legislation unconstitutional in 1998 in Clinton v. City of New York because it violated the Presentment Clause of the Constitution by giving the President the ability to amend legislation presented by Congress. Congress may try establishing a modified version of the line-item veto, as Senators Carper and McCain proposed in 2011 to allow the President to reduce or eliminate earmarks and other non-entitlement spending and require Congress to vote on objectionable items sent back by the President. Otherwise, a line-item veto would likely require a constitutional amendment to be implemented, making its feasibility very challenging. The regular disputes and brinkmanship surrounding raising or suspending the debt ceiling must also be addressed. Congress may consider several debt limit reform options to reduce this source of dysfunction, which has already caused downgrades in the United States’ credit rating in 2011 and 2023, raising borrowing costs for the US Treasury. Congress could require the integration of debt limit increases in the budget resolution and allow automatic debt limit increases or suspensions if the fiscal targets in a budget resolution are met. Any changes to the debt limit would require amendments to 31 U.S.C. §3101, the codification of the 1917 Second Liberty Bond Act that originally established the debt limit. Congress could potentially also require a debt limit increase vote at the same time as a vote on any significant deficit-increasing legislation so lawmakers are accountable for changes in the debt limit then instead of months or years later. Alternatively, Congress may consider eliminating the debt limit if lawmakers believe that the brinksmanship and risks to the financial system risks outweigh its utility as a method to constrain the debt, currently rising at unsustainable levels. Fortunately, some lawmakers in Congress have already worked on legislation to improve the budget process and restore regular order. The Senate Budget Committee has released a suite of bipartisan proposals to improve the budget process, primarily in the Senate. These proposals would increase the transparency of the budget resolution and its amendment process; impose deadlines to file amendments and limit the total number of votes on Senate floor; require a two-thirds vote in the Senate to waive points of order that have a significant effect on the budget; require the Senate to consider appropriations bills under regular order, with a two-thirds vote threshold to consider any other legislation until the Senate adjourns for its August recess; and create revamped subcommittees to allow for the review of the entire portfolio of government spending or tax policy. Reaffirming the Byrd Rule for budget reconciliation is also key to ensuring that reconciliation adheres to its intended purpose of deficit reduction instead of being an expedited process for enacting major legislation. The Bipartisan Congressional Budget Reform Act, introduced in 2019, covered many of the proposals discussed in this section and can serve as a starting point for negotiations on budget process reform. A key Senate Budget Committee proposal is a new nonpartisan budget concepts commission to review Government accounting rules, which differ in some respects from US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). These budget concepts could include expanding the use of accrual accounting and providing estimates of tax expenditures. Any organization requires proper financial accounting and controls to manage its fiscal operations, and the GAO has raised concerns about its ability to provide an opinion on the reliability of the Federal government’s consolidated financial statements. Tax expenditures in particular are a component of the Federal budget that is often ignored. Under certain circumstances, tax expenditures can function as equivalent to a form of government spending, and they influence economic behavior and reduce revenues. This has consequences for Government accounting rules. In the House, the Budget Committee approved legislation in 2024 to establish a bipartisan fiscal commission to improve the long-term fiscal condition of the Federal government. The bill included a focus on both discretionary and mandatory spending, a strategic objective tied to a sustainable debt-to-GDP ratio, and public education on the issue, along with expedited procedures for consideration in both chambers of Congress. CED has long recommended a bipartisan Congressional committee on fiscal responsibility, and establishing this committee could be a legislative vehicle to enact budget process reforms. In addition to reforms to improve the timeliness of the Federal budget process and promote regular order, the process must also incorporate longer-term planning to address the trends of rising fiscal deficits and better prepare for the challenges our Nation faces. One option is to extend the time horizon for CBO’s baseline budget projections from 10 to 25 years and require CBO to assess the long-term impact of budget proposals and include interest costs for all scoring. Having a budget baseline that adequately accounts for long-term costs of current Federal programs is crucial to developing reasonable targets in the budget resolution. These extended baseline projections would promote a long-term budget focus as well. Naturally, an extended baseline is difficult to project, though the CBO already has experience with long-term projections for Social Security and other programs that make up a significant portion of Federal spending. A longer timeframe for projections also increases the uncertainty of budget estimates, especially in later years. This uncertainty could be addressed through a sensitivity analysis that presents a range of potential outcomes under different assumptions to guide policymakers, as in the actuarial reports for the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds. Another option is to require Congress to set statutory medium and long-term targets for regular appropriations and for the national debt as a ratio of GDP, with a goal of reducing the national debt to a more sustainable ratio of 70% of GDP. These targets could be tied to the business cycle in the form of ratios of GDP to allow for larger deficits during a weak economy and smaller deficits when the economy is strong. The targets must also provide flexibility to deal with geopolitical events, emergencies, and major disasters. Requiring Congress to go on the record with the level of debt it views as acceptable would send a clear signal to voters and financial markets and allow them to hold the Federal government accountable for its fiscal plans. Congress’s long-term targets could also focus on financing for capital activities in addition to the overall financing of the Federal government and the deficits of government operations. Government has a crucial role to play in financing public goods, and the Federal government has the unique ability to raise capital through long-term bonds to invest in infrastructure and emergency preparedness. A comprehensive capital financing plan would highlight funding needs and allow for a coordinated approach to issuing bonds to modernize infrastructure, mitigate climate change risks, and increase military readiness and the industrial base. Recent investments in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS) have demonstrated the need for long-term planning given the complexity of collaboration between Federal officials, state and local governments, and private stakeholders. A long-term capital financing plan would provide additional time to establish permitting and regulatory procedures, bolster supply chains, increase transparency for stakeholders, and build out the workforce necessary to achieve the goals of capital investments. The US also faces a challenging global context with rising geopolitical risks and increasingly costly natural disasters occurring with greater frequency, partly because of climate change. Even a well-functioning Federal budget process will encounter unexpected events that require an immediate and robust response from the Federal government. Lawmakers can pass supplemental appropriations to deal with these unanticipated crises, yet this approach adversely impacts the budgetary targets laid out in the budget resolution and complicates planning and prioritizing resources. To address this issue, Congress could create an emergency reserve fund for natural disasters and other major emergencies to provide funding for these unexpected events that often fall outside the budget process and require supplemental funding that was not considered in budget agreements. The emergency reserve fund could be financed by long-term bonds and must be accompanied by long-term plans to mitigate the risk of natural disasters and geopolitical threats. Implementing better risk management procedures is an urgent task for Congress, as the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Disaster Relief Fund has experienced shortfalls in recent years, an issue that will only become more pronounced as local communities continue to struggle to recover and rebuild from more frequent major disasters. July 12, 2024, marked the fiftieth anniversary of the enactment of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act. This significant anniversary highlights Congress’s poor track record in recent decades with managing the Federal budget process in a timely and orderly manner and emphasizes the need for comprehensive reform of the process. The broken budget process has affected governance in Congress because of the prevalence of last-minute deals, late budgets, regular threats of a government shutdown, and brinksmanship around the debt limit. As our Nation’s fiscal trajectory continues to worsen, the consequences of a broken budget process will only become more pronounced and will be an impediment to the bipartisan solutions needed to reduce rising annual deficits and the unsustainable national debt. The options highlighted in this Solutions Brief serve to improve the timeliness of the process, mitigate challenges to regular order, and incorporate longer-term planning into the development of the Federal budget. Congress should act now to end the dysfunction plaguing the Federal budget process and improve the Federal government’s fiscal outlook, restoring confidence and preserving prosperity for future generations of Americans.

Key Insights

Recommendations

Improve Timeliness

Mitigate Dysfunction and Challenges to Regular Order

Incorporate Longer-Term Planning

Relevant Laws Governing the Federal Budget Process

Key budget process legislation

Persistent challenges to a timely and orderly budget process

Overview of the Federal Budget Process

Key Stakeholders and Committees

Budget resolution

Twelve appropriations bills

Other features

Framework for Reforming Federal Budget Process

Principles for a functioning process

Use of continuing resolutions and supplementals

Options for Reform

Improve timeliness

Mitigate dysfunction and challenges to regular order

Signs of progress on timeliness and regular order

Incorporate longer-term planning

Conclusion

Reforming the Broken Federal Budget Process

February 24, 2025

America in Perspective: Policy Priorities for 2025

January 23, 2025

Policy Priorities for 2025

January 23, 2025

Modernizing health programs for fiscal sustainability and quality

November 18, 2024

Modernizing Health Programs for Fiscal Sustainability and Quality

November 18, 2024

Implementing Strategic Investments

October 21, 2024