-

Email

Linkedin

Facebook

Twitter

Copy Link

Loading...

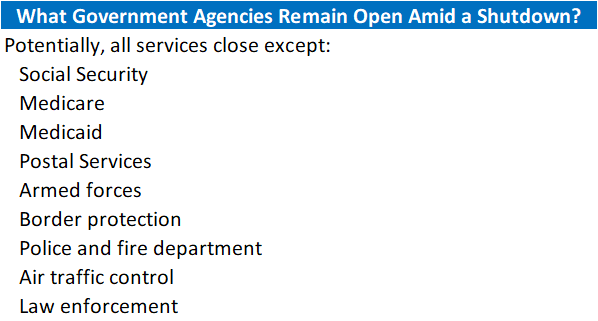

The US Congress is currently locked in discussions on continuing to fund Federal government operations and whether to either raise or suspend the debt ceiling. We have been here before, and it has always worked out—with more or less pain along the way. Indeed, Congress has passed a Continuing Resolution (CR) to fund the Federal government through December 3, 2021. What if come December, we find ourselves on the brink once again? Also, what happens if we hit the public debt ceiling? We explore these possibilities and economic outcomes. Insights for What’s Ahead What are the two issues at hand? What are the policy scenarios regarding the federal government funding and debt ceiling debates? Failing to enact at least a continuing resolution (CR) to fund government operations, and therefore to shut down the government, is perceived as bad politics. Over time, the portions of the government actually shut down have narrowed somewhat; but even so, there is dislocation for the public and a sense of mismanagement. However, it has happened, and fairly naturally has begun a “blame game” in which each side tries to assign the responsibility in the public mind to the other. As the public mind is perceived to settle on one negotiating side to blame, shutdowns tend to come to an end as that side seeks a face-saving way out. Such an exit from the conflict could come even sooner if either side perceives a settling in the public mind in the final moments before appropriations expire. The debt ceiling is a complex issue for mass messaging. People think of the debt ceiling as a device to constrain future spending, rather than as an acknowledgment of responsibility for spending that has already occurred under all past presidential administrations (through the obligation to service the accumulated debt from decades gone by). That has encouraged elected officials to try to use default as a political bargaining chip. In every past episode, cooler heads have prevailed in the end, although the Treasury came to a frightening flirtation with default in 2011 before a deal was struck. Thus, there is a tendency to wait until the debt limit comes close—but not too close. Whether today’s policymakers have become emboldened to get even closer to default than they did in 2011 is a question yet to be answered—and one that is important, given the other vulnerabilities of the economy, including the Delta variant and the fragility of supply chains. What happens if Congress fails to fund the government? If a continuing resolution is not passed on December 3 to fund the government for several more weeks to allow for further negotiations, or in a better case scenario, an omnibus bill is passed to fund the government over a period as long as the remainder of the 2022 fiscal year, then there will be a federal government shutdown. If no appropriation bills are enacted into law, then there would be a “total” federal government shutdown; many government operations, with the exception of those related to the protection of life, property or safety (which would include the services necessary to process entitlement payments such as Social Security), would be halted. If the Congress were to pass some appropriations bills, but not all, then a partial shutdown would occur in only those agencies whose funding has lapsed. Government agencies have contingency plans in the event of a shutdown. What will be the fallout of a shutdown? Recent government budget impasses, even only partial shutdowns, are not without economic and financial market implications. Here we cite several negative externalities: What happens if the debt ceiling is not suspended or raised? According to Treasury Secretary Yellen, the federal government’s debt limit must be raised by October 18 or the US faces the prospect of default. The CBO and private sector forecasts indicate that a breach might be delayed until as late as mid-November. The consequences of this unprecedented situation are unknown. But in all likelihood, if the debt limit is breached, payments for government services would be limited to the inflow of cash, the government would lose its authority to issue Treasury debt, and the US would go into default. Potentially the Treasury might have options including prioritizing government payments (e.g., principal and interest for government securities, Social Security payments, and veterans benefits), although it is unknown whether the Treasury’s payment systems have the capacity to sort among the many claims that come in from all federal agencies every day. Other options include even issuing IOUs sold and traded in private markets, or minting a trillion dollar platinum coin that is deposited with the Federal Reserve to fund obligations. However, these suggestions have largely been rejected by government officials as there are doubts over the feasibility and legality of these options. In the event of a default, most likely one or more credit rating agencies would downgrade the US sovereign debt rating, which currently stands at or near AAA depending upon the agency. A lower credit rating could mean higher costs for borrowing for the US government when Treasury securities are offered for refundings. Even if the ceiling is not breached, there looms risk of a downgrade and souring of markets on US government debt. During the 2011 debt ceiling debacle, at least one rating agency downgraded the US’ sovereign debt rating, even though a breach never occurred. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that wrangling over the debt ceiling raised government borrowing costs by $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2011, with continuing incremental increases in costs in subsequent years. The GAO estimated that the 2013 debt ceiling impasse raised borrowing costs over the following 12 months by roughly $38 million to more than $70 million, depending upon the estimate. Not only are borrowing costs for the US government raised in the event of default, but investors might lose interest in US Treasury debt. US debt may no longer be seen as a “safe haven” asset as the full faith and credit of the US would be undermined. Any incremental loss of faith would have financial consequences. A US government default may have direct implications for borrowing costs for US businesses as well. The creditworthiness of a government, or sovereign, has a direct impact on the perceived risk of any debt-instrument denominated in that sovereign’s currency. Typically, sovereign debt is seen as the least risky debt instrument in a given currency and the rating of this debt creates a ‘ceiling’ that sub-sovereign and private sector debt ratings cannot penetrate. In essence, no debt issued in a specific currency can be less risky than that of the sovereign’s debt – a ‘sovereign ceiling’. In the event that the US government defaults on its debt and its credit rating is downgraded there could be a cascade effect on all other US dollar denominated debt as well. Because of this, borrowing costs for US businesses may rise in the event of a US government default. It has been reported that some financial institutions are required to hold reserves in only the highest-rated securities—which raises an imponderable question of how those institutions—as well as the federal government and Treasury securities—would be affected if Treasury securities would be downgraded to a lower rating. More broadly, the ratings of other institutions and businesses that hold Treasury securities in reserve might suffer a knock-on effect if those Treasury securities in their reserves would be downgraded. What are the global implications of US sovereign debt default? A US default on its sovereign debt would also produce negative reverberations around the world. In the immediate aftermath, there would be a massive sell-off in financial markets that might lead to another global financial crisis. Importantly, investors that have been using US Treasuries as collateral for loans would be forced to swap out these securities for a higher quality of debt. Moreover, the sell-off and likely recession would weaken the US dollar. This would have negative implications for economies whose currencies are pegged to the dollar, potentially causing massive bouts of inflation in those markets. A significantly cheaper dollar would reduce the ability of US firms and consumers to buy goods and tradable services from abroad and would increase inflationary pressures, weighing on global trade and thereby global GDP growth. Meanwhile, cross-border transactions that are typically settled in US dollars would become more expensive if the contracts lack anti-default clauses. Over the longer-run, foreign capital likely would flow away from the United States, as investors would be wary of investing in US Treasuries. This would be quite serious as some of the biggest purchasers of US debt are foreign governments, especially China. Also, the US dollar would run the risk of losing its status as the world’s “reserve currency.” This would lessen the United States’ influence globally, as the dollar is used to facilitate global trade, transactions, and operation of globalized financial markets, and would shake confidence more broadly, in the US’ ability to provide leadership on the world stage, given its problems at home.

Retail Sales Show Consumers Stock Up ahead of Tariffs

April 16, 2025

US Seeks Shipbuilding Revival, Muting of China Dominance

April 14, 2025

March CPI May Hint at Consumer Pullback as Tariffs Rise

April 10, 2025

The US-China Trade War Escalates

April 09, 2025