We are at cyberwar. Here is what firms need to know and do about it

September 05, 2022 | Report

Insights for What’s Ahead

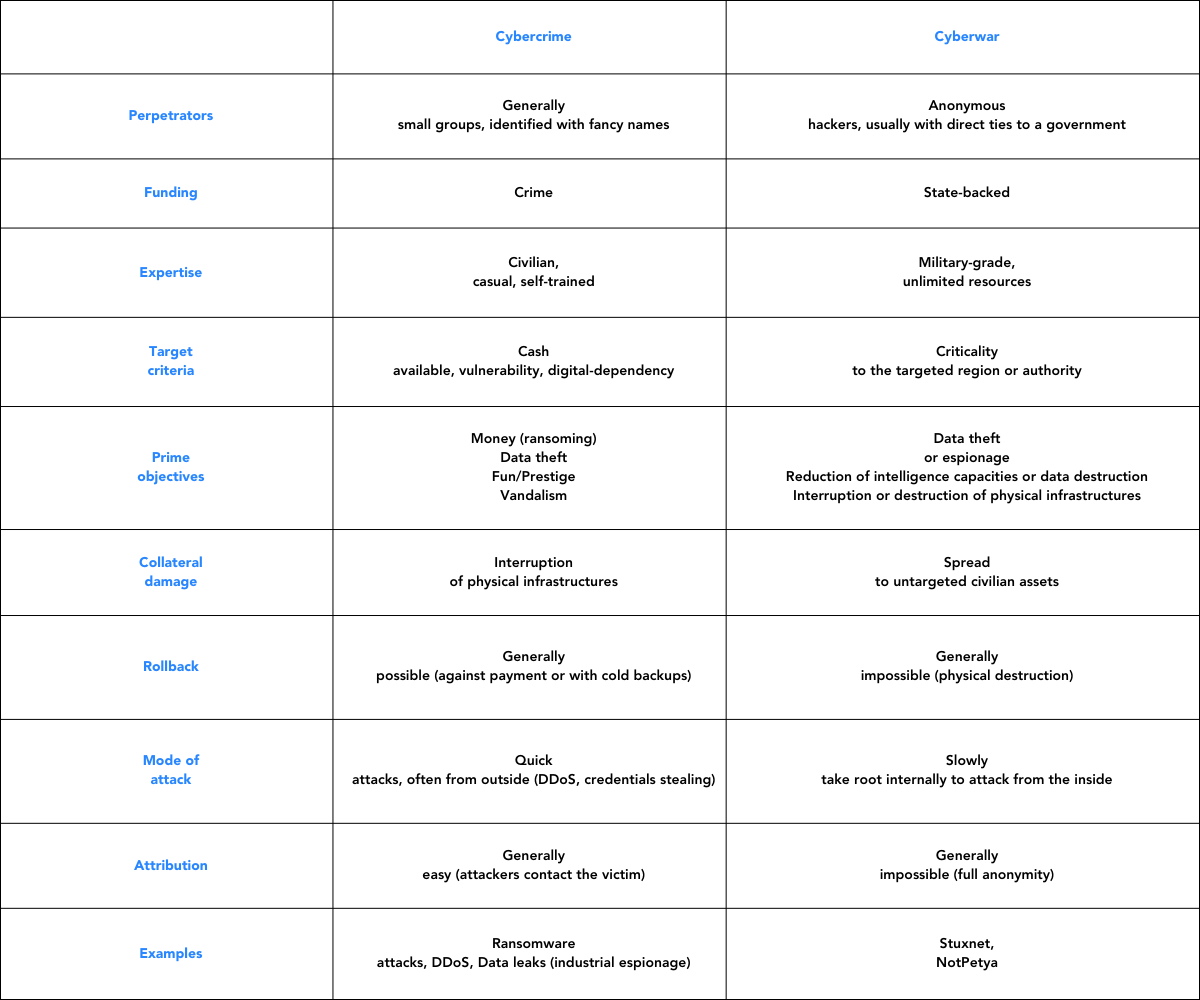

- The war in Ukraine has unleashed new waves of cyberattacks. There are important differences between cybercrime and cyberwar: cybercrime usually stems from private groups, more or less identified, primarily motivated by financial gain, who therefore target cash-rich and data-dependent institutions. In contrast, cyberwar is about causing severe damage to critical digital or physical infrastructures, whether military or civilian. Attacks are different in nature, very hard to attribute, and very sophisticated, but firms are often the unintended victims as an attack spreads through globalized value chains and interconnected information systems. Physical assets have become cyber targets, creating a “phygital” version of cyberthreats.

- Firms need to prepare to protect themselves against both types of attacks. A first step is to precisely map all interconnections and interdependencies of information systems throughout the supply chain, including those with local subsidiaries and local partners.

- A zero-trust policy throughout the supply chain is the cornerstone of security. It consists in building systems that are secured by design, with exposed interfaces that must be limited, tightly monitored, subject to strong credentials verification, and constant auditing.

- Despite such systems, restoration capabilities in case a disaster occurs are key. More than ever, a solid disaster recovery plan is the only possible insurance.

From Cybercrime…

Everybody has heard of cybercrime and the threat of malware. When corporates think of cyber risks, they generally think first of cybercrime: data corruption, theft of information, ransoming based on crypto lockers, distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks which freeze e-commerce websites, and so on. With cybercrime, attackers are indeed mostly after the money and tend to launch attacks that are limited in time and aimed at extracting money rather than causing damage. Cybercriminals are usually made of relatively small groups, often identified with fancy names, whose objective is to create temporary damage or obtain a ransom. If a target is not responsive, attackers quickly move to the next one in row. Whether against payment or thanks to cold backups, it is often possible to roll-back to the pre-attack situation. The list of business victims of cybercrime keeps growing every year.

…To Cyberwar

Then there is cyberwar. What’s fundamentally different with cyberwar compared with cybercrime is that attackers are state-backed and generally a lot more sophisticated and resourceful. They aim at causing persistent damage or disruption. Targets are not guided by financial potential for ransoming but by criticality to the targeted region or authority. Destruction is more likely to be the ultimate goal. As a result, there is generally no way back after such an attack. In contrast to cybercriminals, who most often attack from the outside (DDOS, credentials stealing, crypto lockers), (para)military hackers often take time to make their way inside the organization and take root internally before launching the attack from the inside. They also remain anonymous, making attribution extremely hard or impossible. Their victim will generally not even know where the attack is coming from.

For some years now, cyberwar has become an ugly reality. Stuxnet, the computer worm that destroyed nuclear infrastructures in Iran in 2010, is presumed to be a cyberweapon jointly developed by the US and Israel. Reports of civil and military infrastructures (such as powerplants) being severely damaged or destroyed on both sides of the Russia-Ukrainian border, without any evidence of missile bombing or physical sabotaging, are accruing. For instance, in December 2015, the power grid of Ukraine was hacked. It resulted in 250,000 homes, hospitals, transportation networks, and manufacturing plants being left without electricity for several days. The attack was due to a worm known as Petya (in reference to the dangerous space weapon in the James Bond movie Goldeneye), the origin of which points at the Russian GRU. A new version of this worm, called NotPetya, has been responsible for further attacks on critical infrastructures in Ukraine for the past few years. Lately, Microsoft reported that it had detected an attack on computers in Ukraine by a new malware called Foxblade on February 23, a day before the launch of the Russian war on Ukraine. Conversely, the Ukrainian government’s data center received one of the first missiles launched from Russia. This illustrates how the war has brought a “phygital” version of cyberattacks to the world. Cyber sabotage is no longer a theoretical concept, it is happening in the real world, although much of it unfolds under the radar of the general public.

Cyber blurs the line between crime and war

When the US established cyberspace as a full-fledged domain of war 12 years ago, they may have fooled citizens and corporates into believing that cyberwar would be about state powers fighting over digital networks, and that it was something they needn’t care about. However, with cyberwar, the border between war, crime, and sabotage is increasingly hard to draw. Conflicts, such as in the Donbass, have become a playground to deploy and assess the capabilities of the new cyber powers. The threat, even to the physical assets of businesses and civil society, is very real.

First, criminal attacks can cause physical infrastructures to grind to a halt as a side effect. In May 2021, for instance, the Colonial Pipeline was interrupted as a result of a ransomware attack. This is due to the growing reliance of physical assets on digital systems: disruption of a digital asset may force the shutdown of a physical one. Second, cyberwar is not confined to military targets. Military attacks may target civilian assets and infrastructures (such as powerplants) as well. This shouldn’t come as a surprise. After all, governments have long been relying on cyber intelligence to spy on military, government, industrial, and civilian targets (hello Edward Snowden). But third, and perhaps even more importantly, attacks on military targets may easily spread to untargeted businesses. FedEx learned this the hard way when it became an unforeseen casualty of the NotPetya attack on a Ukrainian power plant. The worm spread to the Ukrainian manufacturing industry and, subsequently, to a local subsidiary of TNT Express—itself a subsidiary of FedEx. The attack quickly expanded to core systems of FedEx and created immense turmoil and disruption within its entire logistics infrastructure not only in Europe but also in the US. The overall cost of damages estimated by FedEx lies somewhere between $300 and $400 million USD.

The hidden vulnerability of global value chains

The spread of the NotPetya attack to FedEx reveals two critical elements. The first is that in cyberspace, there are no formal borders between countries or between civil and military infrastructures. The second is the extreme intricacy of information systems along value chains. Subsidiaries have local connections in addition to their main data- and systems-sharing with corporate data and systems. Systems within and across firms are increasingly communicating through external application programming interfaces (APIs) or through microservices. Microservices and APIs often call other microservices and APIs in a chain of interactions that is often invisible and hard to trace. The extreme modularization and interconnections of IT systems over the past 2 decades has created a very dense web of interdependencies. In a way, this is the digital reflection of global supply chains. Local lockdowns, such as a container ship stuck in the Suez Canal, are enough to bring global supply chains to a halt. The same can be said for the impact of a “local” digital shutdown in cyber supply chains.

Modularity combined with a high density of interconnections form the defining ingredients of highly complex systems. Unfortunately, Perrow’s theory of natural accidents perfectly applies to such systems, suggesting that accidents are unavoidable, tend to escalate, and cannot be designed around. In Perrow’s theory, system accidents often have a relatively small or local beginning but have a tendency to cascade unpredictably through the system to create a large-scale catastrophe. The reasons for and solutions to such cascading disasters are of an organizational nature.

Advice for Corporates: Adopt a Zero-Trust policy, Backed by a Disaster Recovery Plan

What should firms do about cyber risks? Things like endpoint protection software and distribution of data assets across different geographies are a must. But the starting point for business cybersecurity is to map all system interconnections and interdependencies, especially with those countries that are on the offensive or targets themselves. Absent such an exhaustive mapping, it will be impossible to even assess the exact assets to protect. There’s obviously an urgent need to map the current situation, but to maintain an up-to-date view, due diligence procedures need to be adapted to also include cyber dependencies throughout partners and supplier networks. This approach allows for the identification of critical paths, i.e., where cyberattacks will more likely disseminate and ultimately reach an entire business and its partners.

Since interorganizational relationships are reflected through the interconnection of IT systems, there’s widespread confusion between business trust and cyber trust. In the world of cloud architectures, “zero-trust” is widely adopted as the methodology. The interfaces exposed between the companies are limited, tightly monitored, and subject to strong credentials verification and constant auditing. Systems and networks should then be compartmentalized or segregated through the equivalent of firewalls. Safety is achieved by means of a bit of paranoia, but for the good of all.

Despite a zero-trust policy, should any incident occur, responsiveness will be the key to resilience. In the world of cyber blitzkrieg, detection capabilities allow to quickly react and isolate local threats to avoid cascading consequences, sometimes unexpected by the attackers themselves. Emergency procedures need to be established, documented, and rehearsed.

Cyber capabilities have brought war into the corporate world. This is a reality that will become ever harder to escape. In the face of cyberwar, insurance companies are very unlikely to cover damage, even when the risk of cybercrime is covered. A zero-trust policy makes your key defense line. A solid disaster recovery plan is your only insurance.