-

Email

Linkedin

Facebook

Twitter

Copy Link

Loading...

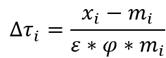

On April 2, the President announced sweeping tariffs on US imports to address bilateral trade imbalances in goods that the Administration believes stem from unfair trade practices. The announcement triggered widespread market disruptions, concerns about economic growth, and threatened retaliation by some countries. In response, the Administration paused the implementation of many of the most severe tariffs for 90 days, though the situation continues to evolve quickly. On April 2, the President signed an Executive Order implementing broad new tariffs, including a 10% duty on all imported goods, with some exceptions, and increased rates between 11-50% on goods from 57 countries. Some items are exempt, including those covered under the United States-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) agreement, copper, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, lumber, certain critical minerals, and energy and energy products. Others are subject to different tariff rates pursuant to other policies (e.g., steel and aluminum, automobiles and automobile parts, and de minimis items from China). Notably, the President later threatened “major” tariffs on pharmaceuticals, which have been exempt from tariffs for decades. The new tariffs are the latest steps taken by the Administration to respond to what it views as unfair treatment of US exports in foreign markets through both tariff and what it claims are non-tariff trade barriers, including value added taxes (VATs) and alleged currency manipulation. The baseline tariffs took effect on April 5 and the country-specific tariffs were scheduled to take effect on April 9. On April 9, however, the President paused implementation of the new tariffs – other than the 10% baseline tariff – for 90 days to give countries an opportunity to negotiate. He did, however, raise tariffs on China to a total of 145% (a 20% baseline tariff and 125% “reciprocal” tariffs) in response to China’s imposition of 34% tariffs on US goods to match the 34% additional tariff imposed by the US. China then raised tariffs on US goods first to 84% and then to 125% and restricted imports of US films (a move with greater cultural and economic impact), while noting that the respective rates “no longer have economic significance” because most US exports to China are no longer financially viable. Despite the pause on the country-specific reciprocal tariffs, goods from Mexico and Canada not covered by the USMCA and steel, aluminum, automobiles, and auto parts of any origin continue to be subject to a 25% tariff. Before the announcement, the Administration had largely targeted the US’ major trading partners – Canada, Mexico, China, and the European Union (EU). It had also imposed sector-specific tariffs on imported steel, aluminum, automobiles, and certain auto parts. Additionally, tariffs of up to 25% were threatened against any country importing oil from Venezuela. However, the new tariffs are significant not only in their broad application but also in their magnitude, marking the highest levels of tariff rates imposed in nearly a century. This shift signals a marked departure from decades of US trade policy that emphasized liberalization and multilateral and bilateral agreements, reflecting a growing turn toward protectionism aimed, in the Administration’s view, at reshoring supply chains, addressing perceived trade imbalances, asserting economic leverage in global affairs, protecting national security, and generating revenue to reduce the Federal deficit. The Administration calculated the “reciprocal” tariffs in an unusual way. They are not true reciprocal tariffs on goods nor do they reflect a weighted average. Instead, the Administration claimed that the tariffs announced April 2 reflect half of what the Administration determined were the penalties other jurisdictions imposed on US exports, including tariffs, non-tariff barriers, and alleged currency manipulation. However, information later shared by the Administration instead stated that the rates reflect “the tariff rate necessary to balance bilateral trade deficits between the US and each of our trading partners.” The Administration calculated this rate using the following formula where xi is total exports from the US to that country, mi is total US imports from that country, ε is the price elasticity of demand (PED), and φ is the elasticity of import prices to tariffs. The Administration assumed ε equal to negative 4 and φ equal to 0.25. Many economists, including some cited by the Administration, have criticized this methodology for lacking a basis in economic principles and for flawed assumptions. A trade imbalance between two countries is not necessarily caused by trade barriers but reflects underlying capital flows and is shaped by factors such as national savings and investment rates, exchange rate movements, growth patterns, comparative advantages, and consumer preferences. In fact, research indicates that tariffs are ineffective at reducing trade imbalances. In addition, the Administration’s approach focuses exclusively on trade in goods, overlooking services (e.g., software, movies and music, financial services, and tourism), which represent approximately one-third of total U.S. exports. In many cases, this creates a misleading impression of a bilateral trade deficit when the US holds a trade surplus with that country (as well as an overall surplus in trade in services). The methodology also lacks a foundation in established trade theory and ignores international, business, and consumer responses to the imposition of tariffs. Beyond questions about the economic reasoning underlying the policy, the assumptions underlying the key parameters of the formula used to calculate the reciprocal tariffs raise additional concerns. PED reflects how sensitive demand is to changes in a product’s price – an elasticity of negative four implies that a 1% increase in import prices would reduce imports by 4%. However, this may be an unrealistic assumption – PED varies across types of goods, but research indicates that PED for most consumer goods typically ranges between 0.5 and 1.5. The Administration also assumed a pass-through rate of 0.25, implying that only 25% of the tariff cost would be reflected in the prices paid by U.S. buyers. However, empirical research consistently shows that the vast majority – if not all – of tariff burden is passed on to consumers, suggesting that a pass-through rate much closer to 1 would be more appropriate. While the effects of adjusting these assumptions may partially offset one another, their individual flaws raise substantive concerns about the rigor and credibility of the overall approach. The Constitution grants Congress the authority to “regulate Commerce with foreign nations” and “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises.” However, Congress has delegated this authority to the President through several statutes – the Tariff Act of 1930 (also known as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act), the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, the Trade Act of 1974, and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) of 1977. Under certain provisions (Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act and Sections 201 and 301 of the Trade Act), a Federal agency must conduct an investigation before the President may impose tariffs. However, under IEEPA, the President may “regulate” or “prohibit” imports to respond to an emergency declared under the National Emergencies Act. Traditionally, IEEPA has been used to impose sanctions or freeze assets of foreign countries – until 2025, no President had invoked IEEPA for tariffs. At the President’s direction, Federal agencies issued a report on the causes of US trade deficits and unfair trade practices by other countries. It is not clear that the report would have satisfied the statutory requirements under the Trade Expansion Act or Trade Act for investigations. Section 301 of the Trade Act also requires consultations with foreign governments before tariffs can be imposed. However, the Administration presumably wanted to keep its proposed rates private in advance to encourage countries to negotiate without knowing the US’ full position. Instead, therefore, the President invoked his authorities under IEEPA, which offers broader flexibility but is legally vulnerable and has already been challenged in at least one lawsuit. The April 2 Order had uneven impacts across countries and regions, reflecting both differences in trade exposure and discretionary decisions by the Administration. No new tariffs were applied to Canada or Mexico, for example, though previously announced tariffs remain in place. On the other hand, because of the methodology used to calculate the tariffs, Asian countries, which export a significant amount of goods to the US, were among the hardest hit. The tariffs also disproportionately affect some African countries, though these impacts may be muted somewhat by the fact that large percentages of their exports to the US are energy products (i.e., oil and gas) as well as critical minerals that are currently exempt. However, some countries could be significantly impacted – diamonds account for about 25% of Botswana’s GDP and 80% of exports, and exports of denim and diamonds account for about 10% of GDP in Lesotho. The tariffs also signal that the African Growth and Opportunity Act, a 2000 law which provides duty-free treatment to certain goods from about 30 African countries, is unlikely to be renewed when it expires in September – the new tariffs effectively take away favorable treatment under AGOA. Taken together, the Administration’s tariff policies represent a significant shift in US strategy, which in recent years had emphasized “friendshoring” – derisking supply chains away from China, a geopolitical adversary, to still lower-cost, but friendly Southeast Asian nations (e.g., Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia) as well as Mexico and others in Latin America. However, the Administration has placed some of the highest tariffs on these nations, a move that some analysts warn could push them closer to China and deepen economic integration (in Asia) through the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. Even before the April 2 announcement, several jurisdictions had announced retaliatory actions in response to earlier tariffs. For example, China threatened tariffs of 10-15% on a variety of US agricultural goods and placed restrictions on 15 US companies doing business in China. China stated said that it “is willing to resolve differences through consultation and negotiation, but if the US insists on its own way, China will fight to the end.” China is seeking to work with the EU, ASEAN, and others to form collective opposition to the tariffs. The new tariffs significantly expanded the countries impacted by US tariffs and drew sharper responses from those already affected. Canada also imposed 25% tariffs on about $20 billion in US goods, including meat and dairy products, beverages, clothing, and other items. The EU also planned 25% tariffs on about $28 billion in US goods targeting beef, poultry, motorcycles, and other goods, but paused these measures on April 10 to allow time for negotiations. Mexico had also threatened tariffs, though President Claudia Sheinbaum delayed announcing details while she negotiated with President Trump. China also responded with high retaliatory tariffs (84%) on all US goods, prompting the Administration to respond by increasing tariffs on Chinese goods by 50 percentage points. China later raised its tariffs to 125% on US goods. Other nations have chosen not to retaliate immediately, instead taking a more conciliatory approach. Indonesia, for example, offered to increase purchases of certain US goods (e.g., cotton, wheat, oil, and gas) while also considering reforming local content laws that the US sees as non-tariff barriers. Vietnam and Taiwan both offered to eliminate tariffs on all US goods, Vietnam also planned to restrict certain exports to China and crack down on Chinese goods being shipped to the US through Vietnam. Japan quickly initiated negotiations with the US. These varying approaches reflect different domestic and geopolitical considerations across jurisdictions. For example, China has reduced its reliance on trade with the US in recent years, giving it greater flexibility to respond forcefully to what it views as US efforts to hinder its economic development, a “red line” it had communicated during bilateral meetings in 2024. The EU’s more targeted approach reflects its dependence on a stable relationship with the US and preference for resolving disputes through multilateral negotiations. However, by not yet targeting US exports of services, the EU has retained options for escalatory measures. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) bloc pledged “frank and constructive dialogue . . . to ensure a balanced and sustainable relationship” rather that imposing “any retaliatory measures.” But reflecting concerns over the consequences of US policies, ASEAN also pledged to deepen regional trade integration and seek “economic cooperation with new partners.” It remains unclear under what conditions the Administration would consider reducing the proposed tariffs. The Administration reportedly initially rejected offers from Vietnam and the EU to eliminate all tariffs citing persistent trade imbalances as evidence of “non-tariff cheating.” It is also unclear whether these countries could realistically purchase enough US goods to close the trade imbalances, or whether the US goods and resources (e.g., oil and gas) are sufficiently price competitive to alternative sources of supply. Since the tariffs were announced, financial markets have declined sharply, economic growth forecasts have been revised downward, and concerns about rising inflation have intensified. The S&P 500, for example, fell about 10 percent in the two days following the announcement, extending losses that began as earlier rounds of tariffs were announced in February. The Conference Board also forecast sizable shocks to growth, inflation, and employment even if other countries do not retaliate. This includes a 1.2 percentage point drop in US GDP growth, a 1 percentage point increase inflation, and the potential loss of 1.1 million jobs by the end of the year. Consumer sentiment also plunged and concerns about a recession rose. Trade conflicts with China threaten to increase prices US consumers pay for many electronic goods (e.g., smartphones and televisions) as well as machinery and appliances, toys, furniture, and plastics, including components of automobiles. US farmers may also be impacted as 47% of US exports of soybeans and related agriculture products exported by the US went to China. It is unclear whether the 90-day pause on implementation will assuage those fears. While markets rose sharply on the news and some analysts lowered expectations for a recession, others noted that uncertainty is itself damaging to economic growth. The economic outlook remains highly dependent on changes in the Administration’s policies and the evolving international response. The economic and market volatility triggered by the tariff announcements has prompted some Congressional actions. For example, bipartisan groups of legislators in both the House and Senate have introduced bills that would require the President to notify Congress of any new tariffs and obtain Congressional approval for them to remain in effect beyond 60 days. The Senate also voted to end the emergency declaration the President used to impose tariffs against Canada, though the House is unlikely to pass the measure. Prime Minister Lawrence Wong of Singapore, a country strongly dependent on global trade, recently addressed the dangers of the current situation. He noted that “[p]rotectionism is already bad, unstable protectionism is even worse.” He highlighted the threat of a full-blown trade war and noted that “[o]nce trade barriers go up, they tend to stay up. Rolling them back is much harder, even after the original rationale no longer applies. Even if some partial accommodations are eventually worked out, the uncertainty generated by such a drastic move will dampen global confidence. It will be very hard to restore the previous status quo.” Further, the bilateral, nation-specific tariffs undermine the whole principal of Most Favored Nation status which underpins the global trading system and the World Trade Organization, raising the risks of a “rising ‘me first’, win-lose mindset – where it’s every country for itself.” Beyond the immediate impact on trade from the tariffs, there remains the broader risk of increasing decoupling of world trade, particularly between the US and China, and the increasing division of the world into geoeconomics blocs – with the new complication that the US has imposed tariffs on many of the countries that count among its closest friends and economic partners, which if it continues, may push the US further in the direction of autarky. China, too, is increasingly reliant on domestic demand for its own growth. Diversion of trade – and deliberate attempts to avoid the US market – become a greater possibility; a new Lego factory in Vietnam is only one symbol of a worrying trend. Despite the current pause on the most severe tariffs, this remains a dynamic and unpredictable policy area that warrants continued close attention. The Conference Board will continue to follow these developments closely in our Navigating Washington hub.

Key Insights

Background on Announced Tariffs and Current Status

Methodology for Reciprocal Tariffs

Legal Considerations

Geoeconomic and Geopolitical Considerations

Retaliatory Actions

Potential Economic Impacts

Congressional Action?

Conclusion