A new demand for flexible working presents opportunities to imaginatively redesign work—but also poses challenges and risks for European employers.

COVID-19 has been a game changer for attitudes toward flexible working. The ability to work flexibly—both in terms of hours and location—is now seen as a priority by many workers, who have had their eyes opened to the benefits and possibilities while working at a distance during the pandemic.

A similar shift has occurred at the top of business. The disruption of the pandemic caused senior leaders to adopt a wider view of flexibility as fundamental to business survival. However, if businesses are to adopt new flexible work models, newfound enthusiasm will need to translate into hard-nosed commitment to change. For various reasons, flexible working across Europe has never become a norm, and is often associated with job insecurity. Less than 20 percent of employees in the EU28 worked part time, and an even smaller portion—only 12 percent—worked from home prior to the pandemic.[1] Without a fundamental willingness to rethink foundational principles around flexible work, outmoded assumptions and unequal practices could prevent businesses partnering with their employees to redesign work imaginatively for a postpandemic future.

The talent imperative

The effect of the pandemic and the wholesale temporary shift to remote working during national lockdowns has caused a dramatic change in worker attitudes toward flexible work across Europe. The employees that companies most rely on to power the postcrisis recovery now expect to be offered opportunities to work when they like, where they like—and may be prepared to quit and seek employment elsewhere if these choices are denied them.

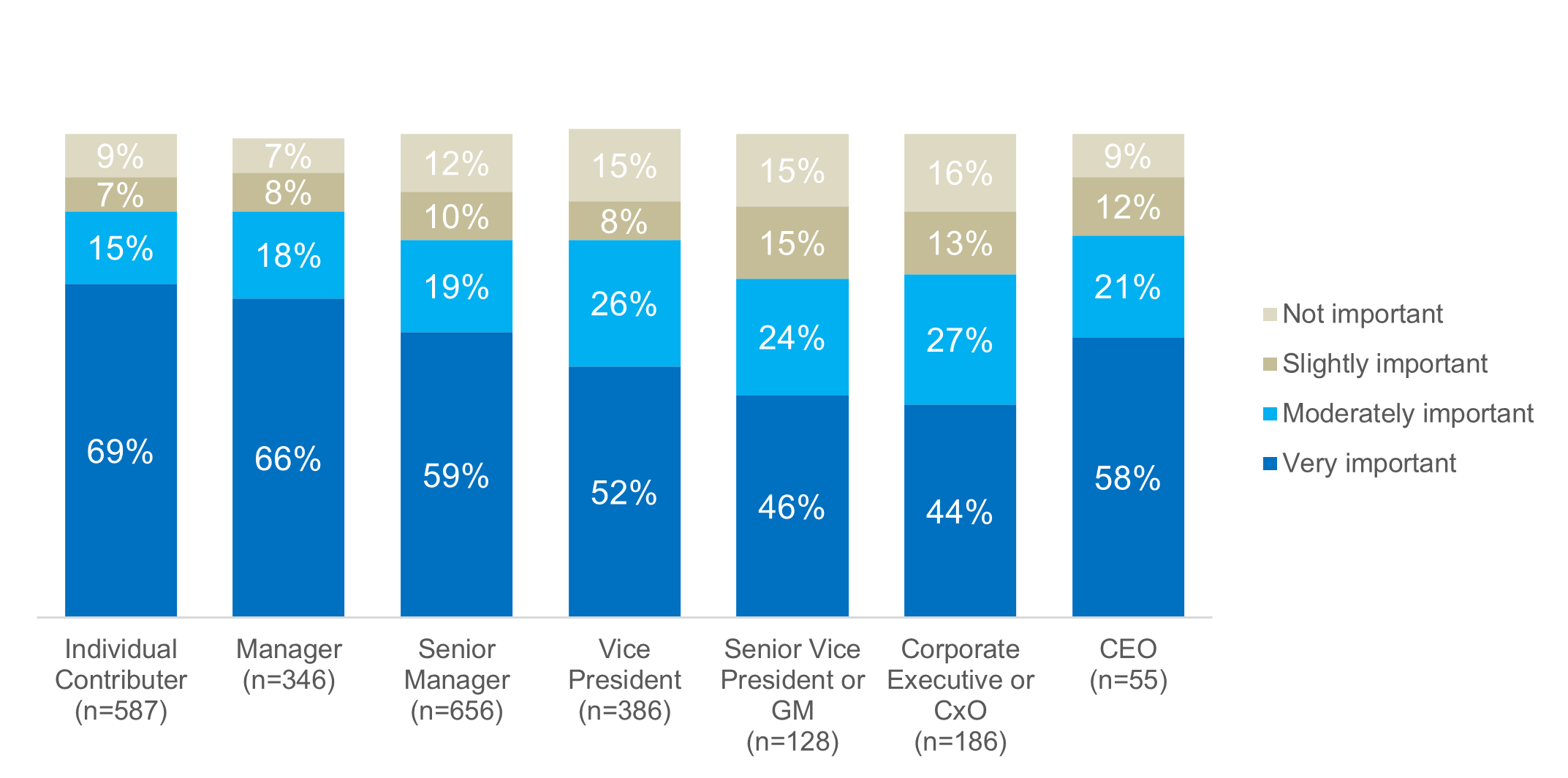

Our work at The Conference Board shows that in a tightening labor market, flexible working is becoming a competitive edge. According to a new survey by The Conference Board, more than one-third of workers may leave their jobs within the next six months. “The driving factor: a desire for flexible work arrangements.” Of those respondents planning to leave their organizations within six months, flexible work location was ranked as the most desired aspect of a new job, prioritized slightly over better pay and career advancement, the two traditional drivers of job changes.[2] This research plus other labor market indicators from The Conference Board suggest that companies with flexible work arrangements are successfully attracting the top talent of their competitors that have adopted a more rigid stance.[3]

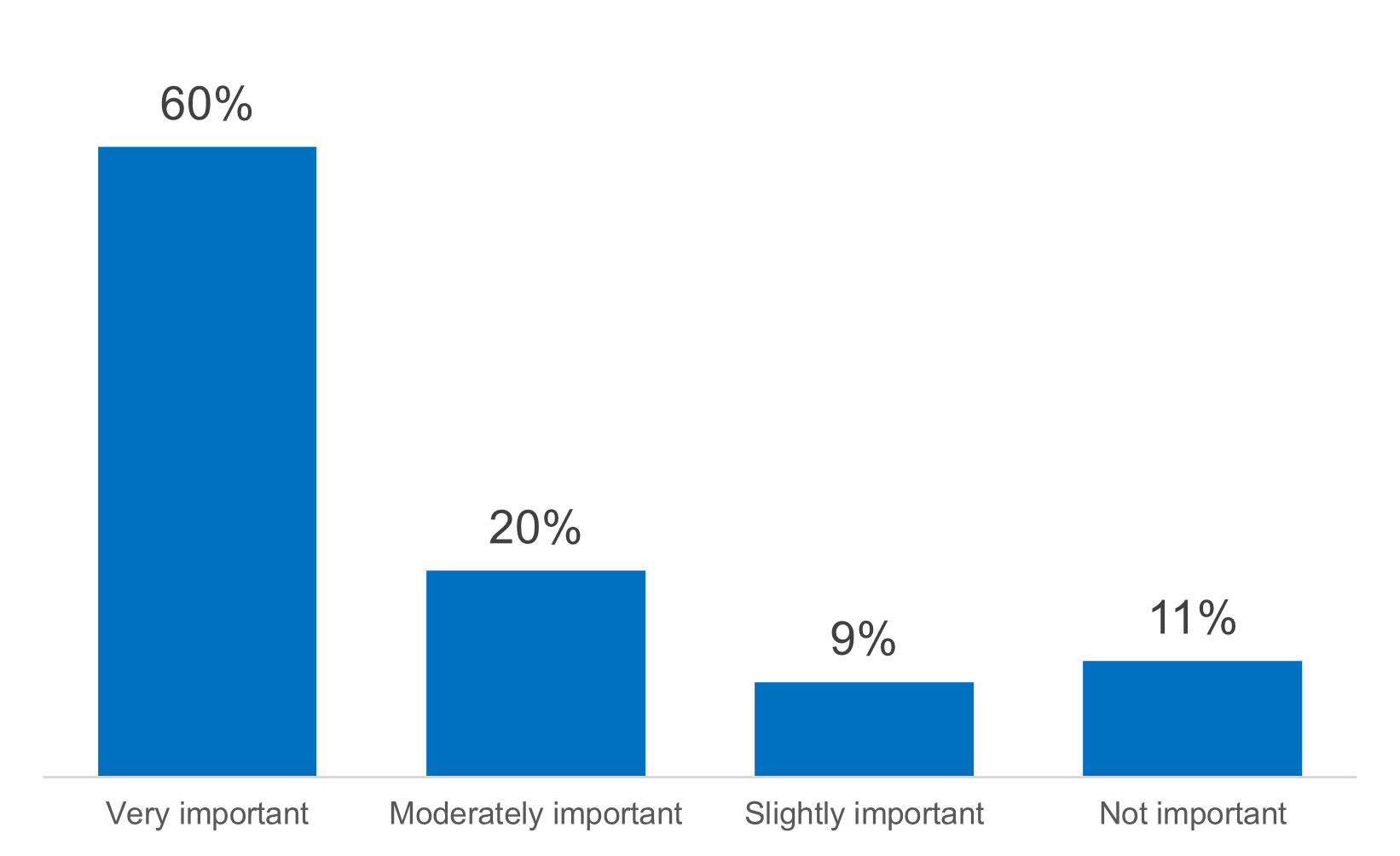

How important was your organization’s stance about work arrangements (e.g., flexibility in hours, work location) in your decision-making to pursue a different position? (n=1,695)

How important was your organization's stance about the following issues in your decision-making to pursue a different position?

The importance of offering flexible work to engage top talent is recognized in the C-suite of many international companies. In our C-Suite Challenge™ 2021, CEOs globally and in Europe rated recruiting and retaining top talent as their number one priority for human capital management. Building agile teams and adopting flexible work policies were among their top five human capital priorities for 2021–2022, suggesting that CEOs are looking for an optimal blend of business and individual flexibility to attract and retain skilled workers.[4]

Flexible working: the new face of employee experience

The previously cited sources suggest that, despite the many complexities and challenges of living and working through the global pandemic, businesses and employees still have identified many benefits of working flexibly, for both them and the organization. These benefits include higher productivity, more personalized work arrangements, and savings on office space.

Most promising of all, flexible work can become thenew face of employee experience and engagement (see “Flexible work is becoming more flexible” for examples of flexible working). With both the C-suite and workers leading the charge for flexibility, tailored work arrangements can move from an often peripheral to a normal way of working. It can become a major lever for inclusion, for example, enabling businesses to tap into workers with disabilities who might prefer more flexibility in working times and locations.

When it becomes normal for employees to work in myriad of different ways, the boundaries between employed and independent workers will further blur. This will provide valuable opportunities to increase a company’s talent ecosystem, potentially making it easier to parcel out work and projects to remote independent workers.

| |

Flexible work is becoming more flexible

A myriad of newer working arrangements is emerging, offering the opportunity to organizations and workers to achieve a win-win situation with improved productivity, business flexibly, and talent engagement and retention. Newer forms of working include:

Annualized hours—agreeing on an employee’s total number of hours to be worked per annum.

Phased retirement—workers can opt for additional holidays and regular free days in the run-up to retirement. This can include a working time reduction scheme where the employer continues to pay fully into the employee’s pension scheme.

Split roles—where an individual works in two different roles in the organization or performs a role outside the organization for part of their time.

Employee sharing schemes—where an employee has an employment contract for the same job with two or more employers. The employers allocate between themselves responsibility for pay, tax, and social security.

Retire and return programs—rehiring retired workers for project work of limited duration.

Hybrid working—where the employee works an agreed number of days from home or at the office, with considerable flexibility as to which location.

Location agnostic working—where employees’ location and postal address is no longer relevant to their employment contract and hiring criteria, so long as they perform their agreed tasks and responsibilities.

|

|

Embedding flexible working: challenges and opportunities

Many companies are now looking to expand their flexible work schemes or transpose temporary measures put in place during the pandemic into permanent, enterprise-wide policies. The scale and complexity of this task should not be underestimated, as major issues need to be considered to ensure employees do not run afoul of worker expectations and/or legal requirements.

1. Legal compliance

National laws across Europe governing rights and responsibilities for flexible working and particularly working remotely are in a state of flux, creating various dilemmas and risks for international companies.

Many European countries have hastily introduced regulations to require employers to allow suitable employees to work at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. These regulations are temporary, but in some countries, they are the precursor to more permanent legislation. Existing and emerging regulations can differ significantly in several ways:

Definitions of flexible work—for example, German law distinguishes between home working and mobile work, with different responsibilities required from employers and employees.

Legal provision—remote work has long been recognized in some European countries such as the Netherlands, but other countries have no specific legal provision for this form of employment. Employers have most of the decision-making power via the employment contract, company policy, or negotiations with employees on a case-by-case basis.

Risk of creating a permanent office for the company—in some countries there is greater risk that an employee working remotely may be seen as creating a permanent establishment for the employer, raising the specter of paying corporate tax in that country.

Compliance with working time legislation—in many European countries, no matter where an employee is located, their employer is responsible for complying with working times, rest periods, and breaks. Any international company scaling up remote and hybrid work will need to commit resources to monitoring and recording working hours to ensure compliance with different national regulations.

Intrusive surveillance—as companies look to technology to help monitor working hours, they could risk colliding with regulations protecting worker privacy or cultural mores, which vary across Europe. Making the right judgment call on what is an intrusive use of technology will be critical to avoid reputational damage. For example, one large employer has recently received unwelcome publicity and criticism from trade unions and national politicians for introducing AI-based webcam surveillance for its 300,000-plus remote workers. The webcam conducts random checks for breaches of work protocols, such as workers eating at their desk, looking at mobile phones, or unexplained breaks. The system reportedly takes a photo and sends this to the workers’ supervisor. The company has been forced to withdraw this technology in some countries where the criticism has been especially intense.

2. Fairness and transparency of decision-making

The patchwork approach to flexible working across Europe has created major differences in workers’ rights to request flexible work, and the degree to which they can challenge the decision to withhold alternative work arrangements. In the prepandemic world, decision-making power lay firmly in the hands of businesses. According to Eurostat, the employer determined working hours for 60.8 percent of those in employment in 2019. Workers in Sweden and Finland had the most discretion—workers in Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Hungary had the least.[5]

It is critical to ensure that flexible working is not seen as the provenance of the privileged few. There is solid evidence that historically, the benefits of flexible working have been far from equal. According to Eurostat, in 2019, women and young workers were less likely to decide on their working time compared to men and older workers. More highly skilled workers also have a greater say over how they work. Data from Eurostat reveals that the higher the education level, the higher the chances people can decide by themselves on their working time—30 percent of those with a high educational attainment level compared to 12 percent of those with a low educational attainment level.[6]

If a large number of employees want to work more flexibly or remotely, international businesses need to devise fair and transparent policies. Without these, variations in workers’ rights and privileges across Europe could lead to charges of discrimination. This variation could also become a source of resentment and disengagement if employees see some colleagues enjoying greater degrees of choice and flexibility.

Stigma and discrimination

In the postpandemic world, employers and workers can leave behind the legacy of stigma and discrimination that is sometimes associated with flexible work. Stigma can be the result of a workplace culture that places more value on employees who work full time and in the full view of their colleagues and supervisors.

Those working more flexibly may be perceived as less committed or less hardworking. A survey of 1,600 civil servants by King’s College London in 2019 found that 25 percent felt their superior saw their flexible working as a negative, and 35 percent felt the need to put in extra hours to show their commitment. A study of working families in 2019 revealed that parents working part time had a 21 percent chance of promotion within the next three years, compared to 45 percent for full-time colleagues.[7]

Employers are likely to see increased pressure to demonstrate equality and equity in flexible working through rigorous data monitoring and reporting of recruitment and retention, pay, career progression, and access to learning and development opportunities for flexible workers and other staff.

However, transparency might not be enough to prevent charges of discrimination if companies decide to permanently reduce the pay of remote workers, as Google has done in the US and PwC is reportedly considering doing.[8] Google is taking an open approach by developing a pay calculator based on location, which enables employees to see the impact on their pay if they decide to work remotely or move to other offices.[9] Besides the potentially demoralizing effect of pay cuts for remote staff, companies would have to ensure they do not infringe employment contracts or unintentionally widen the gender or disability pay gap if certain groups of workers are more likely to opt for working from home.

Monitoring and supporting workers’ well-being

The pandemic has highlighted the need and expectation for companies to safeguard their workers’ psychological well-being. Our research into the impact of COVID-19 on workers has revealed that a reported increase in productivity appears to have come at the expense of well-being for those working remotely.[10] Companies monitoring their workforces have seen more employees reporting a sense of burnout and deterioration of their work-life balance. Workers can also experience isolation and disconnection from their colleagues.

Many prepandemic studies on flexible working suggest that, paradoxically, work-life balance can suffer because workers feel obliged to work longer or more unsociable hours to justify their work arrangement. Managers will need to support and monitor the well-being of those staff who work flexibly to ensure healthy and sustainable practices. An added consideration is the adoption of the “right to disconnect” legislation in a growing number of EU countries including France, Italy, Slovakia, and Ireland. This gives employees the right to switch off their laptops and phones outside working hours, and not to receive, send, or answer any work-related emails, texts, or phone messages. While the goal is to protect workers, an unintended consequence may be to reduce business and individual flexibility, preventing workers from choosing when to connect across different time zones or having the discretion to take time off for personal reasons and making it up later in the day or weekend.

Implications for people management

The expansion of flexible working to the majority of the workforce has important implications for the way companies are managed and the culture it fosters. Among these implications are:

- The need for supervision to be underpinned by greater degrees of mutual trust. If companies want flexible work initiatives to reinforce and support a culture of inclusivity and diversity, trust is the logical accompaniment and an essential requirement in any arrangement based on remote working.

- The need for performance and teamwork to be based on “goals achieved” rather than “time worked.” If employees are given freedom to work when and where they choose, it must be on the basis that they achieve agreed tasks and responsibilities.

- The need for offices to become “hubs,” offering technical backup and facilities that employees may need to access on a regular basis when working from home. Hybrid working will require the shift from individual workspaces to hot desking, with work areas specifically designed for private online study, meetings, and internal conferencing.

- The need for IT upgrading at employees’ homes to facilitate online team and one-on-one meetings and online socializing between colleagues that ensures that individuals working from home do not become isolated.

- The need for consistent and clear policies and procedures setting out eligibility for flexible working, how it will work, roles and responsibilities for flexible workers and their managers, and other related issues such as expenses, IT usage, homeworking, and data protection.

Reinventing flexible work

As highlighted by this report, the increase in the demand for work flexibility, coupled with the wider demands for a shorter working week, is a global paradigm shift that will bring into question everything we thought we knew about the workplace. In a shifting and disruptive environment, business leaders have a unique opportunity to rethink foundational principles around flexible work, jettison outmoded assumptions and unequal practices, and partner with their workers to redesign work imaginatively for a postpandemic future.

To take a bold and imaginative approach to flexible working, leaders should consider the following steps:

- Apply fresh thinking to flexible work arrangements—step out of crisis mode and conduct a strategic review, looking at when and where flexibly working delivers most value to the organization and to individuals, and build your strategy from there.

- Partner with workers to understand their needs and cocreate a strategy that strikes a mutually beneficial balance between organizational and individual flexibility.

- Throw out old assumptions about the kind of work or workers who can work more dynamically—consider the value of flexible working not just for individual workers but also for teams.

- Actively address stigma and myths around flexible working—use data and analytics to ensure opportunities are offered on a fair basis, decisions are transparent, and flexibility does not confer either privilege or disadvantage on different groups of workers.

- Do not underestimate the legal risks when scaling up flexible work arrangements—shore up legal expertise to navigate unclear or conflicting legislation across Europe, and ensure managers and workers understand their respective responsibilities.

We have touched on several implications, but we hope to explore the topic in more depth through ongoing programs of webcasts, council meetings, and upcoming empirical research at The Conference Board.

[5] Eurostat, “EU Labour Force Survey ad hoc module 2019.”

[6] Eurostat, “EU Labour Force Survey ad hoc module 2019.”