-

Email

Linkedin

Facebook

Twitter

Copy Link

Loading...

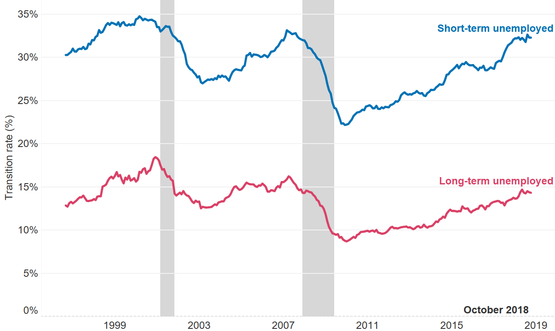

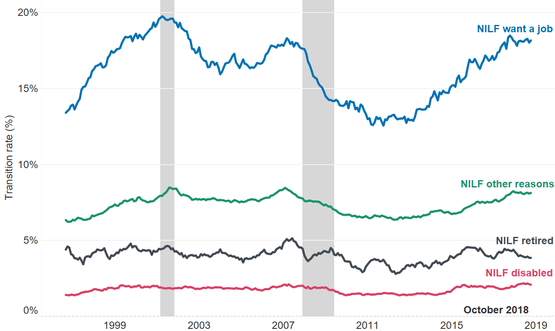

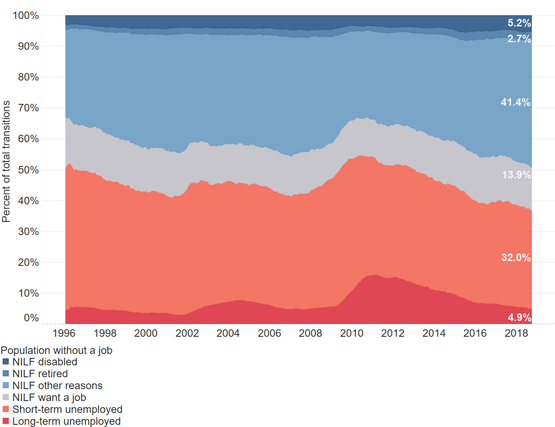

The unemployment rate reached 3.7 percent in November, the lowest rate experienced since the late 60s. At the same time, nominal wage growth has been tepid since the Great Recession and not reached levels expected based on the historical relationship between unemployment rates and wage growth. Recently, there is more evidence showing that wages are growing at a faster pace for blue collar and low-paid services workers following increased tightness in these occupations. Still, national average wage growth has been slow to take off and poses the question: How accurately does the unemployment rate capture labor market tightness? The unemployment rate may be overestimating current labor market tightness. It measures the share of labor force participants who have looked for work in the last four weeks. However, the share of people in the labor force, the labor force participation rate, changes over time and is partly dependent on people’s perception of the strength of the labor market. If people believe chances to find work are low, fewer will actively look for work. The labor force participation rate is currently still below both 2007 and late 90s levels, two previous periods during mature expansions when labor markets were tight. In the last 4 years labor force participation has slowly picked up for men and women aged 25 to 54 (Chart 1). Consequently, as the US economy is strong and news of labor shortages reach people on the sideline, the labor force participation rate may continue to strengthen and prevent further tightening. The unemployment rate is therefore not fully capturing the share of people who might start to look for work soon. Chart 1: Labor force participation rates for men and women, aged 25 to 54, 2000 to October 2018. Another problem with the unemployment rate is the implicit assumption that only people who have recently looked for work influence labor market tightness. While actively looking for work increases one’s chances of finding employment in the next month, others may also end up being employed. To examine the attachment to the labor market for different groups in the population, inside and outside the labor force, this study conducts a flow analysis — an exercise to find the probability of finding employment in the next month. The employment probability is referred to as the transition rate. The exercise shows that 63 percent of all newly employed people aged 25 to 54 in October 2018 were not actively looking for a job in the previous month. Defining transition rates: The transition rate is the probability of finding employment in the next month. It is the share of people who found a job in the next month. In this blog, the transition rates are calculated for 6 groups that together make up the total population without a job aged 25 to 54. The categories are: It appears that the transition rate probabilities for all categories increase the tighter the labor market gets. Chart 2 shows the transition rates of the short- and long-term unemployed, two groups that are part of the labor force. The short-term unemployed, those who have actively looked for work in the last 4 weeks over a period of 26 weeks or less, have currently about a 1 out of 3 chance of finding either a full time or part time job in the next month. For the long-term unemployed, those who have actively looked for work in the last 4 weeks over a period longer than 26 weeks, 15 percent finds a job in the next month. Because the short-term unemployed have a higher transition rate than the long-term unemployed,they are more successful in reaping the fruits from a tight labor market. Chart 2: Transition rates for short and long term unemployed aged 25 to 54, January 1996 to October 2018, 12 month moving average. Source: Current Population Survey, calculations by the author. Chart 3 shows the transition rates for four labor market categories who are not in the labor force (NILF). The NILF want a job group consists of those who say they want a job but have not looked for work in the last 4 weeks. They show similar business cycle trends as the short term unemployed and more find a job in the next month than the long term unemployed. NILF disabled, those who say they do not want a job because of reported disability, seems the least correlated with labor market tightness, though there is still a substantial recent upward movement in transition rates. NILF other reasons, those who say they do not want a job for other reasons than disability and retirement, have a sizeable transition rate of around 8 percent. Only the retired category seems largely impervious to a tightening labor market. Chart 3: Transition rates for NILF groups, aged 25 to 54, January 1996 to October 2018, 12 month moving average. Source: Current Population Survey, calculations by the author. NILF other reasons is especially important when considering its absolute size in the population aged 25 to 54. With a current share of 10 percent in total population it is three times as large as the share of unemployed and NILF want a job combined. The chance of finding employment in the next month may be smaller, its absolute number and increasing share in the monthly newly employed makes NILF other reasons an important source of labor market slack. Chart 4 shows the monthly share of newly employed coming from one of the defined population groups. Since the Great Recession, the share of NILF other reasons finding a job has increased from around 30 to 40 percent today. Even though respondents to the Current Population Survey state that they do not want to work, by next month they may well be employed. Chart 4: The percent of total transition by population group, aged 25 to 54, January 1996 to October 2018, 12 month moving average. Source: Current Population Survey, calculations by the author. Hence, to accurately measure labor market slack, people inside and outside the labor force should be considered. For example, the Non-Employment Index developed by researchers from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond is a useful labor market tigthtness estimator that perhaps more precisely captures the slack in the labor market. Hiring has become increasingly difficult in today’s labor market. Even though transition rates have increased, the group of most likely job candidates — the short-term unemployed, long-term unemployed, and NILF want a job — continues to shrink. Thus, if employers are looking for slack in the labor market, they should find better ways to source and recruit the people who are not looking for work and allegedly not willing to work.

February Jobs Report Hints at Growing Uncertainty

March 07, 2025

Q4 ECI Wage Deceleration Slows

February 07, 2025

Stability Underneath January’s Noisy Jobs Report

February 07, 2025

Robust Job Gains Close 2024

January 10, 2025

November Job Gains Rebound from Disruptions

December 06, 2024

Storms and Strikes Muddy October Jobs Report

November 01, 2024

Charts

Wage inequality continues downward trend in quarter 2 of 2023

LEARN MORECharts

Recent hikes in quits rates indicate retention difficulties across all industries, but have nearly approached pre-pandemic levels

LEARN MORECharts

Decline in office and administrative support work suggests certain tasks and skills have been replaced by automation

LEARN MORECharts

CEOs are having trouble filling positions as the unemployment rate drops lower

LEARN MORECharts

Non-union wages are growing faster than union wages

LEARN MORECharts

This index identifies the risk of future labor shortages for specific occupations.

LEARN MORECharts

Labor shortages and the tightening of labor markets have led companies to lower education requirements when recruiting.

LEARN MORECharts

The rapid rise in job openings to historic highs coupled with increasingly more workers quitting is leading to severe labor shortages, especially in leisure & hospita…

LEARN MORECharts

There has been a large increase in the share of office job ads that mention remote work since before the pandemic.

LEARN MOREPRESS RELEASE

Employment Trends Index™ (ETI) Increased in August

September 09, 2024

PRESS RELEASE

Why the World Is Running Out of Workers

August 13, 2024

PRESS RELEASE

Employment Trends Index™ (ETI) Decreased in July

August 05, 2024

PRESS RELEASE

Employment Trends Index™ (ETI) Decreased in June

July 08, 2024

PRESS RELEASE

Employment Trends Index™ (ETI) Increased in May

June 10, 2024

PRESS RELEASE

Employment Trends Index™ (ETI) Decreased in April

May 06, 2024