Long Expansions Do Not Alone Halt Fast Job Creation

02 Apr. 2018 | Comments (0)

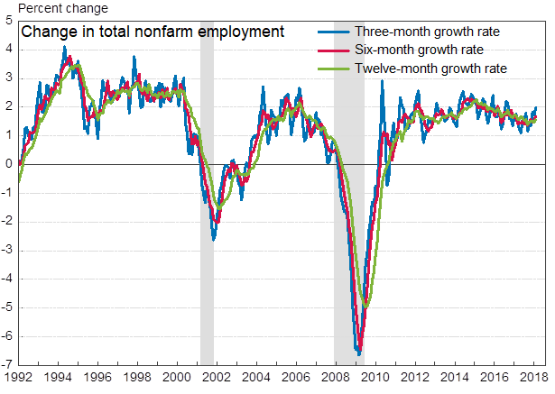

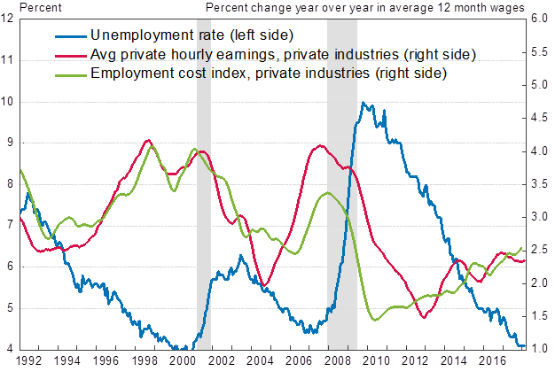

At the outset of 2017, many economists were concerned by the possibility that tighter labor markets would act to slow employment growth. With an expansion entering its eighth year and unemployment below five percent, surely a combination of rising wage growth and the simple inability of employers to find workers would start causing a dramatic slowdown in employment growth. Recent jobs reports, including an eyepopping 314,000 figure for February, signal the opposite. Looking at the history of past expansions, this result becomes less surprising. Yes, employment growth can slow relative to the top of a job market recovery. But job creation ends up sustaining at quite a high rate, at least until recession alarms start flashing.

Source: BLS

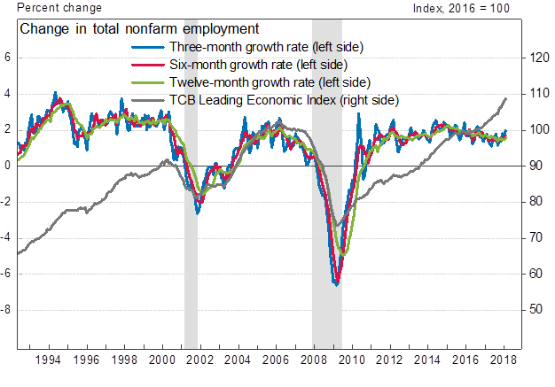

During the 1990s expansion, employment increased rapidly early on, slacked off as economic growth slowed from late 1993 through early 1996, and then growth picked up to well above 2 percent where it remained until April 2000, just 11 months prior to dotcom recession. Job growth began slowing well before the Great Recession in March 2006 and would continue falling until nearly the end of the Great Recession. A sign that expansions and job creation booms die of old age alone? Hardly, based on the behavior of The Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index for the U.S. (LEI) [1].

Sources: BLS, The Conference Board

In both 2000 and 2006, the LEI began heading south at essentially the same time job growth began to slow. Employment growth did not slow gradually, instead employers cut back drastically once they observed other signals that recession risks were rising. Only when the LEI began falling did employment growth start to slow. Rapidly slowing employment growth continued until the forthcoming recessions struck, but it was the LEI that foretold the change in job market momentum.

What does this mean in our current epoch? Year-over-year job growth did peak early in 2015, growing at 2.2 percent on a 12-month basis compared to 1.6 percent now and a recent range of 1.3 to 1.8 percent. This pickup though illustrates that employers are loathe to cutback on hiring during expansions. Restructuring can be demoralizing and disruptive for businesses, so firms often wait until they have no financial alternative before cutting jobs. Except perhaps during the late 1990s, wage growth has not been sufficiently rapid to force firms to act under duress to install labor saving technology. So far, improved labor market conditions have been able to bring new workers back into the labor force to fill ranks as employer demand rises.

Source: BLS

Surely there are limits to how long employment growth can continue unabated. Expansions of the late 1960s and late 1990s had an easier time sustaining fast job growth for longer due to faster working age population growth as well. In contrast, working age population growth (ages 18-64) is now less than 0.4 percent compared to nearly 2 percent in the late 1960s and above 1 percent in the late 1990s.

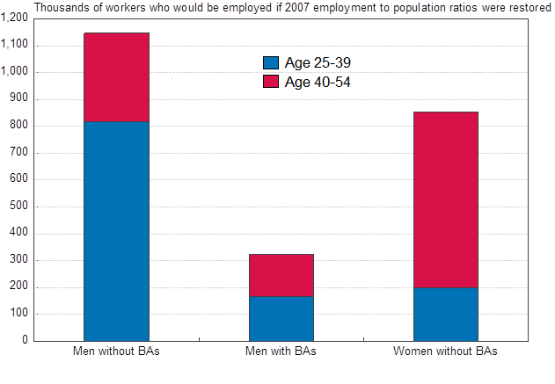

Still, large numbers of plausible candidates remain unemployed. On an age adjusted basis, that is using the difference between 2007 and 2017 employment to population ratios for each individual age rather than for age ranges where the overall age composition of a population matters, progress towards 2007 conditions is better than advertised. All classes of workers, defined by sex and whether they possess bachelor’s degrees (BAs), who are between the ages of 55 and 65, have higher employment to population ratios than they did in 2007. Women with BAs have also regained 2007 employment to population ratios. However, were 2007 employment to population ratios to be regained among men with BAs, men without BAs, and women without BAs, the economy could add over 2,300,000 jobs in the coming years, a figure exceeding 2017’s total job gains. Especially encouraging is that among men without BAs, those who are most underemployed are the 25-39 cohort, who suffered most during the Great Recession and therefore have the most to gain from a continued strong labor market. It is true that many of these potential workers suffered skill erosion due to long spells of unemployment during and after the Great Recession. As employers become increasingly desperate though, lowering qualification standards may in some cases be a more attractive option than raising wages.

Source: IPUMS-CPS, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

In general, exogenous shocks like the dotcom bubble and the housing crisis end expansions before economists get to find out how labor markets will react to ultra-tight conditions. Our current forecast calls for unemployment to fall to 3.4 percent by 2019 if the expansion continues unabated, its lowest level since 1968. Perhaps labor shortages will trigger the next recession as firms will cut back production in reaction to rising costs. Right now though the LEI is still signaling good economic times ahead. A long period of frustration with talent shortages and rising labor costs would likely be required for labor alone to be the next black swan.

[1] The Conference Board’s Employment Trends Index is designed to signal declines in employment levels rather than growth rates and therefore is not as well suited to the task of identifying moments of peak job creation as the US LEI is.

-

About the Author:Brian Schaitkin

The following is a biography of former employee/consultant Brian Schaitkin is a former Senior Economist in U.S. Economic Outlook & Labor Markets at The Conference Board. He is part of a team work…

0 Comment Comment Policy